The complexities of global trade raise questions about how best to address the way countries fairly compensate for their environmental impact on others. Pricing carbon, specifically through a carbon tax, is one such way to address these equity issues and reduce global carbon emissions. We explore the benefits of a carbon tax and what this looks like around the world.

—

What is Carbon Pricing?

Carbon pricing is an approach to reducing carbon emissions that uses market mechanisms to pass the cost of emitting to emitters. Its goal is to discourage the use of fossil fuels, address the causes of the climate crisis and meet national and international agreements.

Well-designed carbon pricing can change the behaviour of consumers, businesses and investors while encouraging technological innovation and generating revenue that can be used productively.

There are a few carbon pricing instruments, such as a carbon emissions tax and cap-and-trade programmes.

Current Situation on Carbon Pricing and Carbon Tax

The International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and others have recommended more stringent fiscal measures to reduce emissions, such as increasing the carbon price or taxation to further incentivise corporations to reduce their emissions and align themselves with the Paris Agreement goals. However, with these plans arise not only political complications such as aligning inconsistent national policies with international trade, but also the issue of equity. With 50% of carbon emissions attributed to the richest 10% in the world, and 10% of emissions attributed to the poorer 50% of the world, it raises the question of who contributes to the climate crisis and who really suffers the consequences of it.

A fair system must be developed, one that acknowledges and compensates for the fact that wealthy nations emit far more carbon than poorer nations, who suffer more from the impacts of the climate crisis. Termed ‘carbon inequality’, efforts are being made to tackle environmental and social injustices through political and economic means.

The discussion around not only pricing and taxing carbon, but developing fair climate policies is not a new one, however there is an increased focus on the degree of responsibility a country should take- how much countries should be paying, and to whom.

At UN climate negotiations in 2018, Chinese delegate Xie Zhenhua addressed the mismatch of cause and consequence between developing and developed countries. He said, “developing countries are not comfortable or happy. We need to see if developed countries have honoured their commitments. Still some countries have not started their mitigation efforts, or provided financial support to poor nations. We strongly urge them to pay up on their debts.”

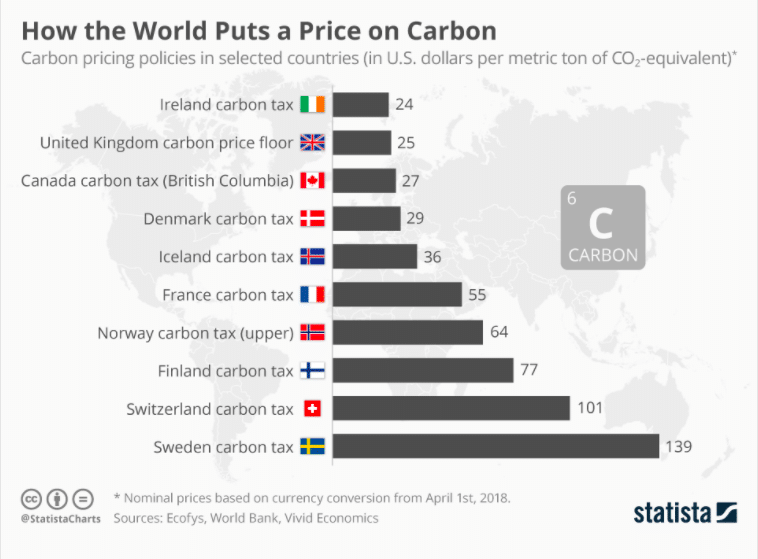

Carbon pricing policies in selected countries (Source: Statista)

Carbon Taxes Around the World

A carbon tax is imposed by a government and is defined by per-tonne tax on the carbon emissions embedded in fossil fuels or other products. It puts a direct price on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and creates a financial incentive to lower emissions by switching to more efficient processes or cleaner fuels.

Cap-and-trade systems such as the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) impose a cap of GHGs that can be emitted every year, called ‘carbon credits’. Those industries with low emissions can sell their extra allowances to larger emitters. This supply and demand for emissions allowances establishes a market price for GHG. The cap helps ensure that emission reductions will take place to keep emitters within their pre-allocated carbon budget.

A national carbon tax is currently implemented in 27 countries around the world, including various countries in the EU, Canada, Singapore, Japan, Ukraine and Argentina. However, according to the 2021 OECD Tax Energy Use report, current tax structures are not adequately aligned with the pollution profile of energy sources. For example, the OECD suggests that carbon taxes are not harsh enough on coal production, although it has proved to be effective for the electricity industry.

A carbon tax has been effectively implemented in Sweden; the carbon tax is USD $127 per tonne and has reduced emissions by 25% since 1995, while its economy has expanded 75% in the same time period.

Where Should the Money Go?

With some carbon tax systems already in place, core criticisms around carbon pricing instruments centre around public trust in the system. Despite long-term environmental benefits, surveys shows that individuals are concerned about how their daily lives will be affected and where revenue will be directed. For example, some concerns include the belief that carbon pricing will add further financial stress on the elderly and those in poorer households by increasing the cost of energy.

Another survey conducted by Nature with 4997 participants in Australia, India, South Africa, the US and the UK proposed different hypothetical carbon tax mechanisms to examine their public’s acceptance to them, whereby ‘funding for mitigation projects worldwide’ received the highest support.

To make carbon taxes politically feasible and economically efficient, governments must choose how to use the revenue. Options include cutting other kinds of taxes, supporting poorer households and communities, increasing investment in green energy or by giving the money back to people as a dividend.

These concerns are already being addressed in some countries such as Switzerland, where residents receive their dividend as a rebate on a compulsory health insurance. Canada’s incoming federal scheme is aiming for 90% of the carbon tax revenue to be returned to residents.

Lack of a Common Commitment

On committing to the Paris Agreement, UN Climate Chief Christiana Figueres said that countries are not looking to save the planet for altruistic reasons. “They’re doing it for what I think is a much more powerful political driving force, which is for the benefit of their own economy,” she said.

There is a disparity between the interconnected global economy and the disparate carbon policies in different countries (some with carbon tax, some implementing cap-and-trade systems, some without a system in place at all). For example, the EU uses their ETS system, yet the majority of the US has yet to implement a carbon tax. These factors make equilibrating the different carbon-pricing schemes on a global basis challenging yet crucial if equity is to be achieved.

Economist Peter Cramton and colleagues emphasise that current ‘pledge-and-review’ processes that came from the Paris Agreement are based on self-interest and that responding only to domestic concerns will not be enough to address the problem at hand. He mentions that Paris was successful in that a collective goal was set, but that individual contributions do not add up.

Another iteration of carbon taxes being discussed is carbon border taxes, as discussed in the EU’s ‘European Green Deal’, which imposes a fee on any product imported from a country that does not have a carbon pricing plan in place. Criticisms about the border carbon tax say that it would discourage international collaboration rather than encourage it.

You might also like: What Countries Have A Carbon Tax?

Is a Shared Responsibility Approach Necessary for Carbon Taxes?

Cramton believes that reciprocity is key in developing policies that drive global climate cooperation. He uses an analogy of a game with a common pot of money; each country has $10, some or all of which the players may simultaneously pledge, and for every $1 (for carbon) that is put into the pot, it is then doubled (by natural climate benefits) and the surplus is redistributed to the recipients.

A referee ensures that they honour their pledges. If individuals are allowed to choose their contributions into the pot, a self-interested member may contribute nothing because they will still reap the benefits, relying on others to contribute to the pot.

However, with a common commitment version of the game, players condition their contributions on others’ pledges: the referee ensures that they all contribute the amount of the lowest pledge. It is a reciprocal, co-dependent model, but does not say what everyone must do – an ‘I will if you will’ mentality.

No one is forced to contribute more than expected, yet everyone gains. If countries are completely selfish, they cannot lose but only gain if they pledge the lowest pledge. Common commitment policies can convert selfish behaviour from ‘contribute nothing’ to ‘contribute everything’ because the concept protects against free riding.

To supplement Cramton’s view, a study posits that to be fair for both developed and developing nations, there needs to be a shift away from a production-based approach to a shared responsibility approach in the form of carbon emission ‘burden-sharing schemes’. The production-based principle means that a country should be responsible for all the emissions generated by its production activities within its borders.

The study views this method as outdated in the context of globalisation because it does not take international trade into account. For example, developing countries such as China would take the burden of carbon emissions associated with exporting goods to developed countries.

Uniform Carbon Pricing

The lack of a central body regulating the implementation of such carbon pricing strategies around the world also hinders this issue of equity. Carbon pricing has been demonstrated as the preferred climate policy instrument, and would also be beneficial to promote international cooperation. To implement carbon pricing globally though, research suggests a ‘global system of harmonised carbon taxes’ rather than one unified global tax so that countries can retain control over revenues.

Cramton believes in the implementation of a uniform carbon price instead. He compares setting different carbon prices to setting speed limits, saying that “if drivers chose their own speed limits, there would be no use enforcing them because everyone would drive at their desired speed.”

To ensure that enforcement strengthens a collective rather than an individual effort, Cramton proposes a global carbon price commitment decided by a voting majority. It would allow a country to choose how it complies, via taxes, cap-and-trade, or other schemes, as long as the country’s average carbon price (cost per unit greenhouse gas emitted) is at least as high as the agreed price.

Incentive Fund

In conjunction with the suggestions above, Economist Raghuram Rajan suggests the creation of a global incentive fund. Rajan posits that there should be a system in place where countries that produce emissions above a defined carbon threshold should have to financially compensate those countries that produce emissions below it.

Essentially, countries that emit more greenhouse gases than others should pay into a fund that rewards low emitters (for example through the Green Climate Fund). Critics of this optimistic, yet idealistic system suggest that it is oversimplistic, failing to take into account other factors such as population growth, existing ecosystems, biodiversity and GDP.

What’s Next For Carbon Tax?

Carbon taxing is just one way of holding large emitters accountable for their role in harming the environment. It represents a departure from the West’s traditional model of letting market forces guide decision-making by allowing governments to mandate emission targets, which is one of the reasons it hasn’t been as widely implemented around the world as it should be. However, if the planet is to have any hope of meeting the Paris Agreement goals, drastic measures that consider both the economic and social wellbeing of nations’ inhabitants must be taken.

You might also like: Cap-and Trade vs Carbon Tax