In 1993, Hong Kong recorded an urbanisation rate of 100%, meaning that all of the territory’s residents were considered to be residing in urban environments. The growth of Hong Kong’s urban areas and its city-dwelling population has largely been predicated on a set of unique policies that have allowed the city to develop despite environmental challenges such as a tropical climate and mountainous terrain. Arguably the most historically popular urban development strategy in Hong Kong has been land reclamation, the process of creating new land by filling in existing water bodies.

—

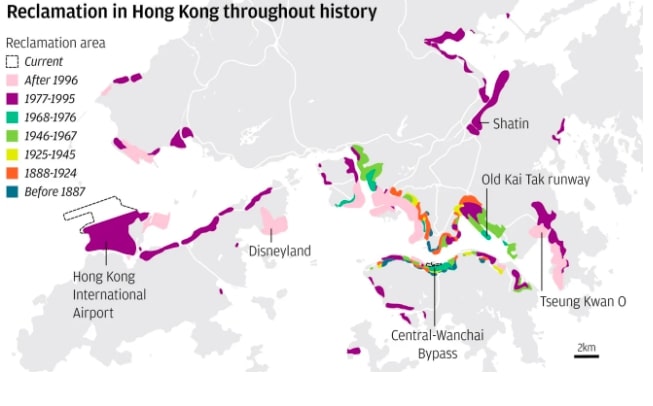

Between 1877 and 2020, over 70 sq km of land has been reclaimed in Hong Kong. The majority of this area was reclaimed in the New Territories and its islands. Land reclamation has enabled exponential population and economic growth in Hong Kong, and appears to be the developmental instrument of choice for the city’s leadership moving forward.

Originally, Hong Kong’s confining topography was not conducive to extensive urban development, as a craggy coastline, steep mountains and limited flat land restricted early settlement options. However, a growing population size since the late 1800s necessitated the creation of new land space. Since the British Empire’s colonial presence in Hong Kong, the city’s chronic overcrowding and housing allocation challenges have made land reclamation an attractive policy for the city’s legislators.

In 2018, reclaimed land represented 6% of Hong Kong’s total area and 25% of its developed land. Reclaimed land houses around 27% of Hong Kong’s population and 70% of its business activities. It is arguable that, without land reclamation, Hong Kong would never have achieved its current status as a global city with first-rate infrastructure. Reclaimed land supports many of the city’s landmarks, including Hong Kong Island’s iconic skyline. Much of the territory’s infrastructure projects were only achievable through land reclamation, including the Hong Kong Airport, the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge and the expansion of the city’s MTR metro system in Victoria Harbour.

Despite being a fixture in the history of Hong Kong’s development, land reclamation as a practice has recently been met with public criticism towards its impact on the city’s natural and cultural heritage. In March, Earth.Org interviewed Dr. Cindy Lam of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology’s Department of Ocean Science, who discussed land reclamation’s contribution to biodiversity and habitat loss. On the topic of Hong Kong’s developmental policy taking precedence over conservation efforts, Dr. Lam stated: “Hong Kong likes to adopt the ‘development first, conservation later’ approach. People have the false feeling that we can preserve habitats and species after development.”

In 2018, the Hong Kong government announced Lantau Tomorrow Vision, a massive land reclamation project off the coast of Lantau Island that will cover 1,000 hectares of artificial islands and house over one million people. The project has revived environmental concerns over land reclamation and has elicited criticism towards a perceived misuse of the city’s fiscal resources.

You might also like: 6 Biggest Environmental Issues in Hong Kong in 2022

South China Morning Post: Visual history of land reclamation in Hong Kong before 2018. Source: SCMP.

A Time-Tested Urban Development Policy

Simply put, land reclamation involves creating new land where there was none before, which can be exploited for new purposes. Land reclamation generally involves filling a selected area with large amounts of rock, earth and potentially cement. The area is then covered and filled with more clay and soil until the targeted height is reached. In Hong Kong, land reclamation projects are normally completed by excavating soil from mountains along the coastline. The debris is then used to either extend the coastline or create artificial islands.

The first modern use of land reclamation as a policy measure in Hong Kong occurred in 1851. In December of that year, a devastating fire consumed 450 homes in the city’s Sheung Wan neighbourhood, leaving behind mounds of rubble and debris alongside Hong Kong Island’s western harbourfront. The territory’s British rulers opted to combine the rubble with soil from nearby hill slopes and deposit it in the harbour to create a new roadway along the coastline. This first land reclamation project extended the shoreline by 15 metres.

Between 1851 and the early 20th century, most land reclamation projects took place off the northern coast of Hong Kong Island where the British colonial offices were located, primarily between what are now the Kennedy Town and Causeway Bay neighbourhoods. Reclamation also took place on the southern end of the Kowloon peninsula. Early reclamation projects were welcomed by the government, as they alleviated health and safety concerns in overcrowded neighbourhoods and homes. Additionally, reclamation works were designed to lower coastal seabeds and allow larger ships to dock in the harbour.

Early reclamation projects elicited public resistance from waterfront landowners and seaside trading firms with docking rights. The government managed to assuage concerns by introducing a payment scheme that invited private sector enterprises to claim ownership of reclaimed land in exchange for paying for the reclamation of the land, thus driving development policy through private capital.

Given the prevailing role of private enterprise in early reclamation projects, the practice was conducted in a regulated but uncoordinated manner until the mid-20th century. Reclamation was an unsystematic urban expansion measure, which meant that the majority of projects were piecemeal private initiatives which rarely amounted to major infrastructural development policy throughout this period.

In the 1950s, Hong Kong’s population began growing at exponential rates, which was largely due to a massive influx of migrants from mainland China. As a response, the Hong Kong government forgoed the private enterprise-driven approach to land reclamation, and intervened directly to create new habitable land to accommodate the city’s rapidly growing population.

The new towns of Kwun Tong (built in the 1950s), Tsuen Wan (built in the 1960s), Sha Tin and Tai Po (both built in the 1970s) were all largely reliant on reclamation, and were the first satellite town development projects aimed at accommodating growing population size and opening up new spaces for economic activity. In 1973, the government consolidated its vision for urban population growth by announcing a new development initiative, termed the New Town Development Programme, focusing on urban development projects across Kowloon, New Territories and Lantau Island. Since 1973, the government has established nine new towns, complete with private and public housing, transportation infrastructure and commercial centres. In 2016, 47% of Hong Kong’s 7.35 million population lived in new towns. Of the nine new towns, six have been built on reclaimed land.

In the 1970s, as mainland China began to open itself to foreign capital investment and become the global epicentre of cheap manufacturing, Hong Kong’s firms moved their manufacturing operations to the mainland. This, combined with the territory’s increasing importance in financial mediation between China and the global market accelerated Hong Kong’s transition to a burgeoning service and trade economy in the late 1980s and 1990s. Land reclamation policy reflected this transition, as projects such as expansion into Victoria Harbour, growth of the city’s port and building a new international airport gained traction.

For most citizens, service economy-oriented infrastructural land reclamation projects did not carry the same benefits as the development of new housing and commercial areas. The large-scale reclamation plan for the expansion of Central and Wan Chai that began in the 1990s elicited a negative public response, which mainly criticised the loss of natural and cultural heritage in exchange for minimal benefits for average citizens.

In 1997, the Hong Kong government passed the Protection of the Harbour Ordinance bill, which categorises Victoria Harbour as a public asset of natural and cultural heritage value to Hong Kong and its citizens, and therefore limits reclamation activities that might damage it.

The bill contained a grandfather clause that allowed previously approved projects to be completed uninhibited by the ordinance. This included the Central and Wan Chai reclamation project which had been endorsed as early as 1989. Additionally, reclamation projects that are able to demonstrate a clear economic, commercial and social value may still be approved pending review.

As reclamation projects pivoted to focus on building Hong Kong’s capacity for a service economy, public reception of the practice turned increasingly negative.

Environmental and Social Impacts

In our interview with Dr. Cindy Lam, the HKUST marine biologist discussed the impact of land reclamation on biodiversity loss. According to Dr. Lam, churned sediment and the deposition of organic and inorganic polluting materials will have a causal effect on marine food webs. More turbulent waters can decrease sunlight and affect marine photosynthesis, and polluting substances can be consumed by smaller fish and increase the food web’s toxicity. Dr. Lam highlighted the unprecedented low numbers of marine species iconic to Hong Kong, including the Chinese white dolphin and the horseshoe crab, species whose habitats have been disrupted by massive land reclamation projects.

Environmental concerns over the protection of Hong Kong’s marine environments are growing due to the increasing interconnectedness of cities along the Pearl River Delta (PRD). While mainland China tends to regulate land reclamation practices more strictly than Hong Kong, reclamation projects connecting infrastructure between cities along the PRD are growing in number, leading to concerns over greater biodiversity and habitat loss for niche species.

Concerns over reclamation projects in Victoria Harbour have also addressed the potential for reduced water flow and water body shrinkage, the harbour is now in fact shrunk to less than half of its original width. Should the harbour’s water flow be slowed substantially, its self-cleansing ability may be severely impacted, a situation only aggravated by reclamation projects increasing water turbidity. A reduction in water volume, combined with urban expansion, would also decrease the harbour’s ability to cool and ventilate surrounding areas, aggravating air pollution and raising urban temperatures.

In addition to the environmental impact, land reclamation harms efforts to conserve Hong Kong’s cultural heritage. The classification of Victoria Harbour as an asset of cultural as well as natural value in 1997 was seen as an important step, although it did little to reverse the modifications to the harbour that had already been carried out, nor did it halt pre-approved massive reclamation projects. Historic Hong Kong landmarks, including the Edinburgh Place Star Ferry Pier and Queen’s Pier in Central were demolished between 2006 and 2008 to make way for reclamation.

Thousands of Hong Kongers turned out to protest the Edinburgh Place Star Ferry Pier’s demolition, vocalising public dissent to further impact on the natural harbourfront. In response, the government pivoted once more to evaluate the potential for mass land reclamation projects outside of Victoria Harbour to satisfy population growth and demands related to the capacity of the city’s service economy.

Lantau Tomorrow Vision

In 2018, the Hong Kong government announced its latest massive land reclamation project – the “Lantau Tomorrow Vision” plan. With a staggering HKD$624 billion price tag attached, the project aims to house 1.1 million people in an economic and residential hub through the creation of artificial islands covering 1 000 hectares beginning in 2026 or 2027. According to the government’s planning concept, the Kau Yi Chau island will create more than 40 million square feet of commercial floor space, the size of Hong Kong’s Central district. It aims to replicate Central’s functions too: the business district will host an extensive transportation network that connects with Central on Hong Kong island, enabling high value-added logistics and business services on par with the development of the Greater Bay Area market.

The government’s push of the “Lantau Tomorrow Vision” can also be attributed to its capability to address Hong Kong’s severe housing shortage. The government envisions an additional 260 000 to 400 000 residential units from the “Lantau Tomorrow” from 2032, completed in stages to meet the housing needs of approximately 700 000 to 1.1 million people. Among these units, the government will look to provide affordable public housing units, for which 80-90% of Hong Kong households are eligible to apply. Based on a public and private housing ratio of 7:3, the remaining land lots can provide quality residential areas to offer the middle class a wider choice in buying their first homes or replacing old ones. Therefore, the Lantau land reclamation project is not only an effective solution to addressing land shortage in Hong Kong, it also provides a strong foundation for capitalising on growth opportunities in the Greater Bay Area.

However, this new space and opportunity comes at a significant cost; with its heavy price tag, it will drain the city’s fiscal reserves, which have already been severely depleted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Even if the government were to lean towards the private sector for help (which it has been attempting to tap into), this would most likely be unable to account for all future costs that will be accrued from the enormity of the project.

The financial repercussions are only the tip of the iceberg. It is the predicted environmental damage from the project that has led to strong resistance from the public. In particular, the land reclamation project threatens to destroy the entire marine ecosystem in the Lantau area. A team of researchers (part of Ocean-HK study led by Professor Jianping Gan at The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) found two seasonal water zones with low oxygen levels near the reclamation site (south and southeast of Lantau Island). Low oxygen levels can create “dead zones,” which will suffocate marine life and cause others to flee the area. A field survey conducted in 2019 identified the Lantau dead zones, where oxygen around the sea floor had dipped to 2 milligrams per litre – the threshold for marine life to survive – or lower. This sort of oxygen depletion – known as hypoxia – may cause irreparable damage to the marine ecosystem.

In addition, further work associated with land reclamation could worsen water quality, lead to a higher proportion of red tides and dead fish and bad odours. Water will likely stagnate as the water’s ability to flush out waste water (discharges from the Pearl River Delta and around HK) will weaken, which will lead to stagnant harbours across the artificial islands. What’s more, the HK government is considering building canals on the islands, with renderings suggesting it will create a much larger volume of stagnant water that would become foul-smelling. Additionally, these artificial islands could decelerate currents around Stonecutters Island to the north, where a treatment plant discharges waste water from the city’s central urban areas. With a worsening dead zone and being surrounded by a discharge point, one could easily make the argument that this is neither eco-friendly or particularly attractive to a potential homeowner.

With these concerns in mind, the government should consider some of the following mitigation measures. For one, the government must conduct a comprehensive impact assessment in order to determine the exact effects that the project will cause. While the government has portrayed a HK$550 million feasibility study as an impact study, it is primarily a planning and engineering study – usually associated as the last step before construction of the project commences. And, of the HK$550 million budget, HK$350 million will be used for engineering design. Another could involve a costly scheme to remove nutrients from sewage across the city before this waste is discharged. While a proposed upgrade of a harbour treatment scheme would achieve this desired effect, the plan would not cover large parts of NT or outlying islands like Lantau. Another method would be that the proposed islands be designed in such a way that major marine passages would not be blocked and currents could be sped up. Ultimately, a comprehensive study examining ocean hydrodynamics, nutrient sources, waste water cycle in the environment and affected ecosystem will be necessary if we are to proceed with any form of land reclamation project.

Land reclamation has been an integral component of Hong Kong’s development since the territory’s colonial era, as the practice has permitted the city to accommodate its population and foster economic growth. Land reclamation appears to be a mainstay of policy planning for the city in the near future, although its strengths must be balanced with environmental security and minimisation of biodiversity loss. The Hong Kong government has adapted its land reclamation policies to different economic needs over the decades; moving forward, the city will also have to consider the needs and demands of its citizenry.

Featured image by: Flickr

You might also like: Renewable Energy Landscape in Hong Kong: Utilising the City’s Potential