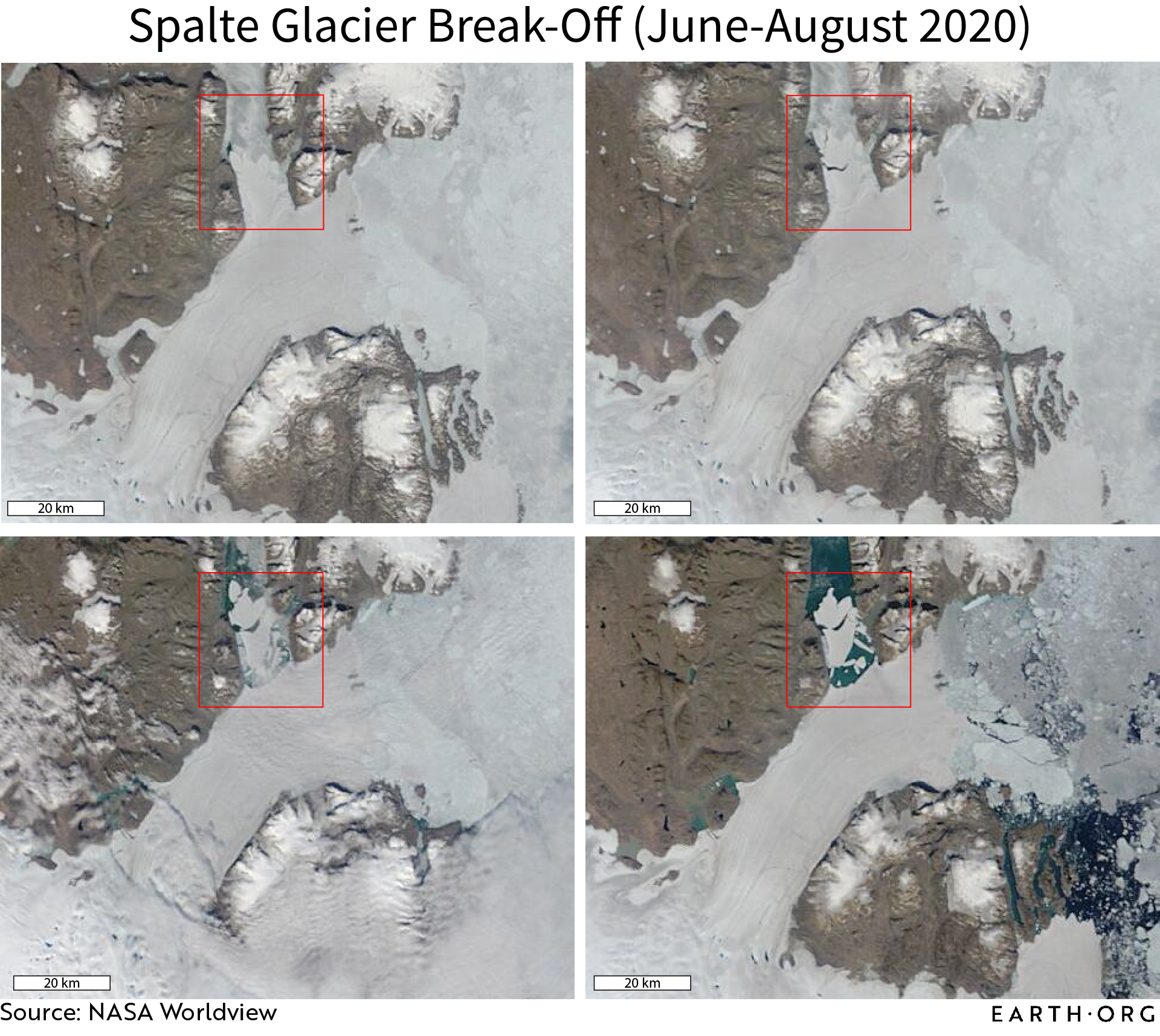

While COVID-19 was the biggest issue of 2020, we at Earth.Org are hoping that as the virus becomes somewhat manageable, the attention will be turned to climate change in 2021. Between the COP25 conference being postponed to this year and a damning WWF report about the decline of species, countries have a limited time in which to act if we are to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change. We have put together 6 reasons why 2021 will be an important year in the fight against climate change.

—

- COVID-19 Has Changed Everything

Besides the human lives lost or shaken in general, COVID-19 has delivered the most significant economic shock since the Great Depression in the 1920s and 1930s. To restart economies, governments have produced stimulus packages, and some have used them as a way to incorporate green spending into recovery plans.

The EU and US President-elect Joe Biden have promised trillions of dollars of green investments to reboot their economies while achieving decarbonisation as well. It is hoped that other countries will join them- and many have pledged to, as detailed later- which will help to reduce the cost of renewable energy globally. Already, a new report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) has found that global renewable energy electricity installation will hit record levels in 2020 compared to the sharp declines in the fossil fuel sectors caused by COVID-19. Almost 90% of new electricity generation in 2020 will be from renewable energy sources. The EU and Biden also say that they intend to stick a tax on imports of countries that emit too much carbon in an attempt to encourage them to clean up their acts.

It is hoped that the world will use COVID-19 to forge a greener path, but countries need to cooperate to ensure that this task is taken on by all.

- Carbon Emissions Have Dropped, But Where To From Here?

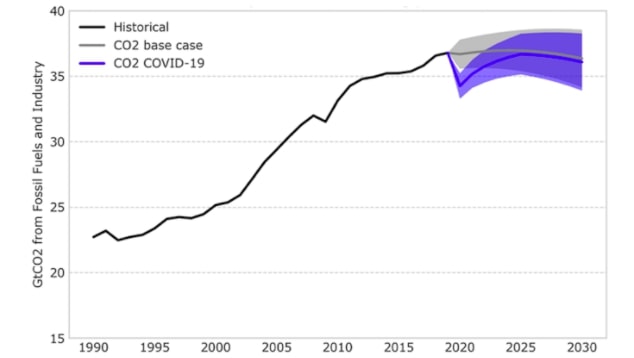

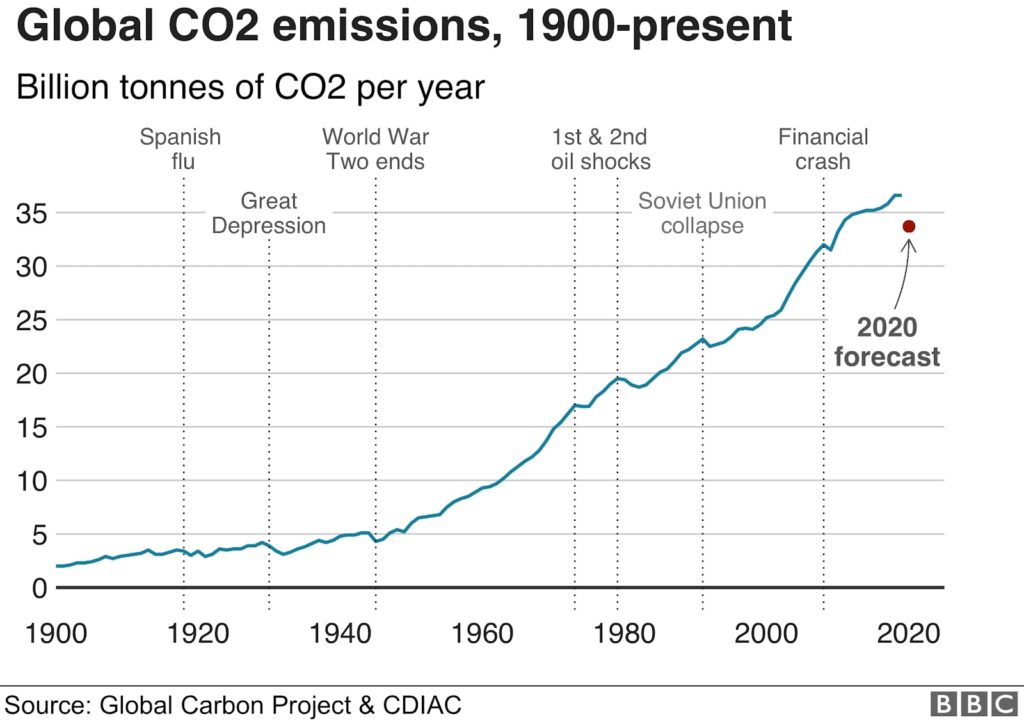

While the annual Global Carbon Budget report says that global emissions dropped 7% in 2020, it will make no difference to long-term climate change. Further, according to the UN, despite the growth of renewable energy, developed nations are spending 50% more on sectors linked to fossil fuels than on low-carbon energy.

This drop is temporary because it was due to behavioural changes, not structural. However, these behavioural changes can become structural; for example, if more people continue to work from home and if cities are made more cyclist and walker- friendly. Other changes, like switching to renewable energy and an increase in electric vehicles, should also be pursued urgently.

According to the IPCC, emissions need to be halved by 2030 if we are to meet the 1.5C goal as outlined in the Paris Agreement. Considering that this year, atmospheric carbon dioxide is set to hit 412 ppm, this can’t come sooner.

You might also like: What Obstacles Do Developing Countries Face When Investing in Low-Carbon Energy Projects?

Source: BBC

- Renewable Energy Sources are at Their Cheapest

In October 2020, the International Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organisation, said that the best solar power schemes now offer “the cheapest source of electricity in history.” In much of the world, renewables are already often cheaper than fossil fuel power when it comes to building new power stations.

If countries ramp up their investments in wind, solar and power batteries, in a few years it will make more commercial sense to shut down and replace existing coal and gas power stations.

Source: BBC

- A Rise in Carbon Neutrality Commitments

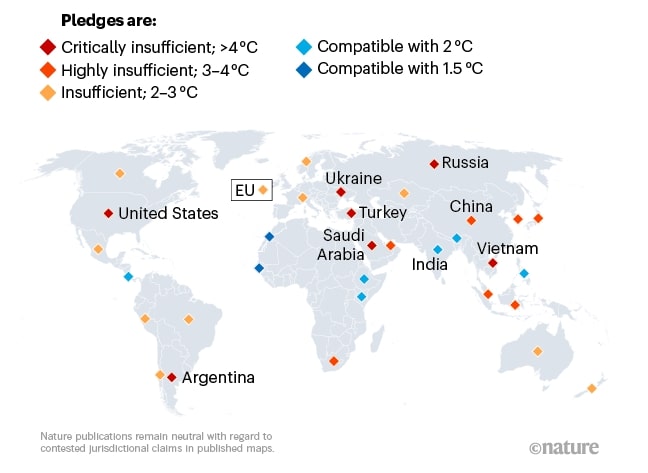

2020 was a year in which many countries, some being major emitters, committed to reducing carbon emissions to zero this century. In September in a surprise announcement, China pledged to reach peak emissions by 2030, and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. In June 2019, the UK pledged to reach zero emissions, followed by the EU in March 2020.

Since then, Japan and South Korea have joined what the UN estimates is now a total of over 110 countries that have set net zero targets for mid-century. Together, they represent more than 65% of global emissions and more than 70% of the world economy, according to the UN. President-elect Joe Biden in the US has made climate change one of the central tenets of his campaign, so it is hoped that in 2021, he can make some headway in bringing down the emissions of the biggest economy in the world.

- Important Climate Conferences

After being postponed last year, the COP26 conference will now take place in Glasgow in November this year, where world leaders will discuss their climate plans. The conference is seen as the successor to the landmark Paris meeting of 2015, which was the first time nearly all nations of the world came together to agree that climate change action needed to be taken by all. However, the world has fallen far short of the targets set by the agreement, which was to keep global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100, but ideally to keep it below 1.5C.

Following current trajectories, the world is expected to breach this 1.5C threshold within 12 years or less and to hit 3C of warming by 2100. It is hoped that Glasgow will allow countries a chance to improve on their previous commitments.

- The Business Community is Going Green

Fossil fuels are becoming an increasingly unattractive investment. Added to this is that the cost of renewable energy is falling and there is mounting public pressure for action on climate, all of which is changing the attitudes in business. Why invest in new oil wells or coal power stations that will become obsolete before they can repay themselves over their 20 to 30-year life?

These “stranded assets” are causing sustainability to come to the fore in the business world- Tesla’s share price has skyrocketed, while Exxon’s has plummeted. Meanwhile, more investment firms are making it clear that they will no longer invest in dirty fuels and that the companies they do invest in must embed climate risk into their financial decision making.

In 2021, it is imperative that countries with big climate commitments follow them up with strategies to achieve them to fight against climate change. This is the hope at Glasgow; that countries will sign up to policies that will start reducing emissions now. We don’t have much more time.