In popular imagination the Arctic is a harsh, dark wintery landscape, hardly the first place one associates with sunshine as a resource. Yet solar power has been increasingly taking hold above the Arctic Circle, in particular among indigenous communities with some of the strongest motivations to become energy independent and reduce the carbon emissions exacerbating climate change.

—

The Pronounced Effects of Climate Change and Diesel on Indigenous Communities

Nowhere on Earth is experiencing the consequences of anthropogenic climate change as visibly as the Arctic. The region is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the world and this is manifesting as severe sea ice loss, decreased land snow cover and accelerated glacier retreat (ref. 1).

For indigenous communities, who have held deep cultural and spiritual ties to the land since time immemorial, these changes are immediate threats to their ways of life. Climate change is not a distant, slowly emerging issue to comfortably debate and someday plan for- it is there, and it is now.

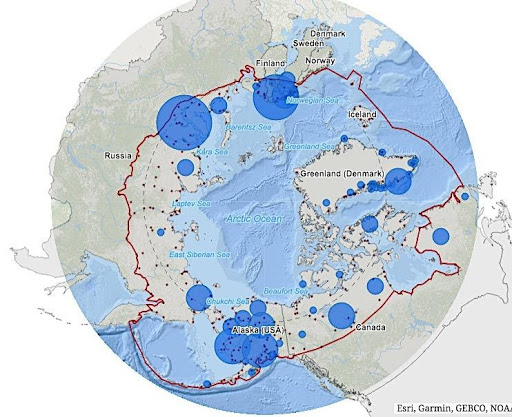

The world’s dependence on fossil fuels for energy is also not only challenging indigenous groups by way of global warming but by keeping the electricity supply expensive and unreliable in their remote northern locations (ref. 2). Many of these communities constitute Arctic settlements outside regional and continental power grids (Figure 1) where it can get extremely expensive to import diesel, the region’s primary fuel source, at times needing to be flown in due to impassable winter conditions.

Figure 1. Indigenous populations’ distribution in the Arctic (blue circles); the AMAP Arctic boundary is shown in red Source: AMAP, Natural Earth

The Arctic is Actually Great for Solar

It might be counterintuitive to think of solar power as very promising in the Arctic but its conditions actually fare quite well.

For one, while winters in the Arctic are indeed dimly lit months, summers there have some of the planet’s longest days, meaning photovoltaic panels can operate round the clock (ref. 3). In the spring, snow reflects sunlight off the ground and further enhances output (ref. 4).

The cool year-round temperature keeps panels from overheating and this makes them more efficient, able to generate up to 25 percent more electricity per hour than in warmer southern regions.

A big issue with solar panels in general is that they need to be regularly cleared and dusted to let sun rays in, but in Northern latitudes panels are tilted up to 45 degrees to optimize solar irradiance, as the sun is ever only so high in the sky, and this lets snow and debris simply slide off.

Given these advantages, plus the last decade’s advancements in this technology, it makes sense that Arctic indigenous communities have increasingly sought to tap into solar power by their own means.

Examples of Solar in the Arctic

Take the Old Crow Solar Project. The community of Old Crow in the Yukon, Canada, a village of about 250 people part of the Vuntut Gwitch’in First Nation, decided in 2008 to seek energy security and independence and has since scaled up to a solar framework that will reduce their yearly diesel use by about 190,000 liters. This translates to 680 fewer tons of CO2e emitted each year. Backed by a $400 million Arctic Energy Fund commitment from the Canadian government, the project’s full implementation was set for this year, and despite being stalled due to COVID-19 residents are enthusiastic to be on what they agree is the right path. Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm explained this as an application of modern technology that embodies ‘our Indigenous values of living in balance with our land in perpetuity (ref. 5).

Another example is the village of Colville Lake, population 160 and gathering area of the K’asho Got’ine Dene First Nation (ref. 6). This community was among the last in the N.W.T. to get electricity at all, and in 2016 became the first to be powered by a solar/diesel hybrid system. Their reliance on imported fuel is estimated to be 40 percent less than average, and during the summer the solar component is the town’s main power source. Residents say there is less noise and less smell of diesel, and they are proud to be moving back towards their roots in self-reliance.

These projects have drawn the attention of other off-grid communities across Canada and the Arctic regions of the US, Finland and Denmark. Organizations like the Indigenous Clean Energy Social Enterprise are helping advance indigenous leadership in the renewable energy sector (ref. 7).

Technological challenges in solar power exist but they are small compared to issues like obtaining supportive national policies and financing, and thoroughly educating and training community members. How well best practices are implemented will largely determine the success of similar projects going forward (ref. 8).

This article was written by Debbie Sanchez. Cover photo from BBC.com.

You might also like: The 2020 Arctic Report Card

References

- https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/arctic-meteorology/climate_change.html

- https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/09/f78/AEO%20Factsheet-%20Energy.pdf

- https://insideclimatenews.org/news/24022020/solar-finland-nordic-renewables-sanna-marin-climate-targets-turku/

- https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200219-the-solar-farms-fighting-climate-change-in-alaska

- https://arctic-council.org/en/news/the-old-crow-solar-project/

- https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/colville-lake-solar-power-1.3604310

- https://indigenouscleanenergy.com/

- https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/best-practices-solar-arctic-infographic/

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://earth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)