Sustainable waste management capacity worldwide lags far behind the continually growing waste production rate. Countries with stricter regulations for disposal therefore must export much of their trash in order to maintain their own standards. Historically, the US and many wealthier members of the EU bloc used China as a dumping ground, but it shook the waste industry in 2018 with a new policy.

Earth.Org takes a closer look

—

Prior to January 2018, China handled nearly half the world recyclables for the past quarter of a century, accepting 95% of the EU’s and 70% of the US volume. Inherent to waste shipping is the inevitable inclusion of contaminated products, whether intentional or not. This left China with an impossibly large amount of plastic it could not recycle, plus a good deal of toxic waste. It had no choice but to enact the “National Sword” policy shortly after New Year’s in 2018.

Since then, richer, more prolific waste producing-countries have been scrambling to find new places to dump their trash. Especially since applying their own waste management standards to so much material would be extremely costly and oftentimes beyond their capacity.

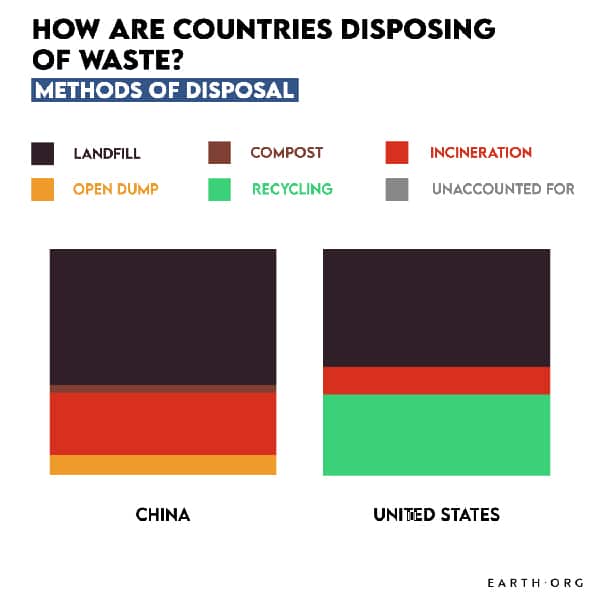

Source: World Bank.

After China’s ban, the US turned to South-east Asian countries, like Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam. Because of how difficult it is to sort and correctly dispose of waste, particularly certain dangerous types, there is widespread exploitation of poorer countries’ lack of regulations for easy dumping. Moreover, these often lack the means and infrastructure for waste processing, meaning much of it ends up in open dumps or is dangerously incinerated, wafting toxic chemicals toward nearby settlements.

For the moment, incineration is on the rise, especially in Europe where waste-to-energy plants are the new trend. These contain most emissions and are a viable solution for the time being, but they still produce harmful pollutants.

Meanwhile, China has one of the largest municipal solid waste volumes in the world, and it is growing rapidly. In order to deal with this, policy and regulations have been set up to create better sorting programs, leading to better management down the line. However, as the largest manufacturer of electronics in the world, it struggles to sustainably handle its harmful e-waste products.

It is seeking to move away from its traditional landfills and develop a blossoming private recycling industry.

Over the coming decade, up to 111 million tons of plastic will have to find a new place to go. The upside is that this could force countries to expand and develop their waste processing infrastructure, resulting in a better situation than before the “National Sword”.

This article was written by Oowen Mulhern.

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)