Air pollution is the third leading cause of death worldwide, and most large cities, have fine particulate matter (PM2.5) levels above WHO health guidelines. Here, we take a look air pollution mapping in Johannesburg to better understand the current situation, and where things may be heading.

—

Air pollution is tightly linked to a country or city’s stage of economic development, so it is helpful to take a look back at its history to understand why things are as they are today.

In the late 19th century, South Africa transformed from what was mainly an agricultural society to an industrialized one. Entrepreneurs of the time capitalized on the massive mineral reserves of the region, diamonds and gold in particular.

Johannesburg was founded as a mining camp of about 3,000 people in 1887, but the gold rush caused it to grow to a town of 100,00 within ten years, then to a city of a quarter million by 1914. Labour force demand was the driving force behind all of this, leading to an extraordinarily compacted, uneven development of the city. Quoted as a place, “of unbridled squander and unfathomable squalor,” large parts of its population found themselves pressured to get by in this runaway urban society.

The main difference between the pre- and post-industrialized society was the new presence of mass production and huge factories. No matter where these appeared, records remain of the fetid smoke belched out the chimneys and difficult working hours, returning home covered in grease and soot.

South Africa’s industry developed later than other countries’, lagging behind England and even Australia, but the result was similar: coal and chemical fume-spouting chimneys popped up everywhere.

In its early centuries, the environmental issues of most concern were drinking water control and rationing, water and land pollution and the conservation of wild animals. This last one became a big issue in the late 19th and early 20th, while air pollution remained largely ignored.

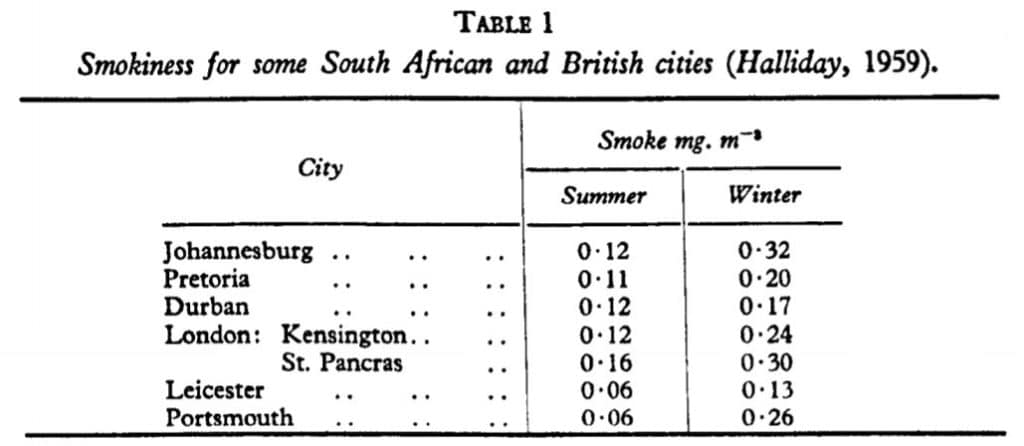

Global concern arose with the London disaster of 1952, where thousands died within days after meteorological conditions created a dense blanket of toxic smog over the city. This prompted many to speak out, and a wave of rudimentary studies appeared. One by P.D. Tyson, published in 1959, cites concerns about South African cities’ “smokiness” being as bad, if not worse than that of British cities. With no differentiation of the types of particles, they measured air pollution in units of actual smoke.

Source: P.D. Tyson (1959).

As you can see, Johannesburg was already one of the most polluted cities of the industrialized world, especially in winter.

As a sidebar: this is an important aspect of atmospheric pollution in general; meteorological conditions will largely dictate whether particles stagnate or get blown away, though of course their amount is also a deciding factor.

Back to Johannesburg, the problem of air pollution was visible, yet governmental inaction persisted. This could be chalked up to the lack of information on the health impacts of noxious fumes. This data was the missing link between pollution and the constitutional right to a safe environment.

A few years later, the Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act of 1965 was the first legislation of its kind in South Africa, though unfortunately it was a largely ineffective piece of legislation. The situation didn’t truly change until 1996 (30 years later!), when section 24 of the South African Constitution robustly enshrined basic environmental rights for its citizens. The National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) came soon after, along with the ratification of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Things were finally moving on a global scale, though South Africans still had to wait until 2004 for the Air Quality Act to come into play, setting precise national norms and standards to regulate air quality. Namely, the particles falling under regulation were sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulate matter (PM10), fine particulate matter (PM2.5), ozone (O3), benzene (C6H6), lead (Pb), and carbon monoxide (CO).

A few or many of these may be familiar to you, but here we focus on PM2.5, the notoriously small particles that can enter deep into the lungs. They have similar health effects to those of smoking, including but not limited to chronic bronchitis, reduced lung function, cancer and heart disease. Berkeley Earth, a climate-concerned think tank, made a conversion formula from PM2.5 to cigarettes in terms of health effects, which we mapped below.

Air pollution mapping in Johannesburg. PM2.5 data from NASA-SEDAC (2016).

PM2.5 air pollution in Johannesburg is, on average, as bad for you as smoking 12 to 14 cigarettes a week. If you think that sounds like a lot, that’s because it is. Most large cities in developed countries have dropped the cigarette index to under 3 a week, many in Europe under 1.

The truth is that Johannesburg’s air quality is lagging behind that of its peers, and its citizens are suffering the consequences. According to a 2019 study, air pollution shaves an average 3 years off the Johannesburger’s life. The combination of vehicle emissions, coal-heavy energy production and forest fires create a serious health hazard which South Africa doesn’t seem ready to take care of.

Policy is filled with glaring omissions like the lack of a vehicle emissions standard; truly a standard nowadays when they are found from Europe to India. A 2019 study estimated a single energy company called Eskom was responsible for over 300 deaths a year in an industrial zone near Johannesburg, prompting a lawsuit against the government. It is still ongoing today, and little progress has been made.

South Africa isn’t doing enough to curb its air pollution, but clean technology is becoming more market-competitive everyday and it will soon be the economically preferable choice to improve things. In the meantime, the authorities are racking up a debt with their citizens that cannot truly be repaid, though reparation is certainly due.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: Melbourne Air Pollution

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)