“Experiencing even the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of the consequences brought by the climate crisis may be exactly what global leaders and negotiators need to accelerate the climate agenda,” writes Chin Chin Lam.

—

By Chin Chin Lam

It is vital to reflect on the progress made at the 2022 Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27), which was hosted in Egypt last November.

COP27 carried an important agenda to actualise previously made climate pledges and to deliver solutions to developing countries on climate adaptation and loss and damage. A historic deal was reached to create a loss and damage fund to offer compensation to the countries most vulnerable to climate change.

But apart from this, the progress made in climate negotiations and actions was disappointing and, frankly, quite underwhelming.

You might also like: Did COP27 Succeed or Fail?

The COP27 venue in the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh generated controversial headlines itself, with some people calling it a simulation for participants to experience the real-life situation of food and water scarcity caused by the climate crisis. Others were discontent with some of the very much non-soundproof negotiation rooms, and the poor arrangements of transportation to the venue.

Chin Chin Lam at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in November 2022. Photo: Supplied.

As someone who attended the conference last year, I unfortunately agree with the sentiments above, in addition to the lack of general hygiene and quantity of washrooms, especially in the Covid-19 era. However, the difficulties of holding one of the largest two-week international conferences in a developing country must be recognised.

When compared with COP26 host Glasgow, Scotland, the disparities between a developed and developing country host are clear. One must be reminded that the reason for such disparity in hosting the annual COP event extends to why developing countries are suffering so heavily from climate injustices.

Developed countries have contributed the most to the current climate crisis through mass industrialisation, which grew their economies, while developing countries suffer the effects of global industrialisation and stolen resources through historic colonialism. Experiencing even the “tip of the iceberg” of the consequences brought by the climate crisis may be exactly what global leaders and negotiators need to accelerate the climate agenda.

The COPs are two-week conferences where global leaders, delegates and civil society from around the world meet and push forward the Paris Agreement, an international treaty negotiated at COP21 that outlined a commitment to keep the mean global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably limit the increase to 1.5 degrees, thus reducing the effects of the climate crisis.

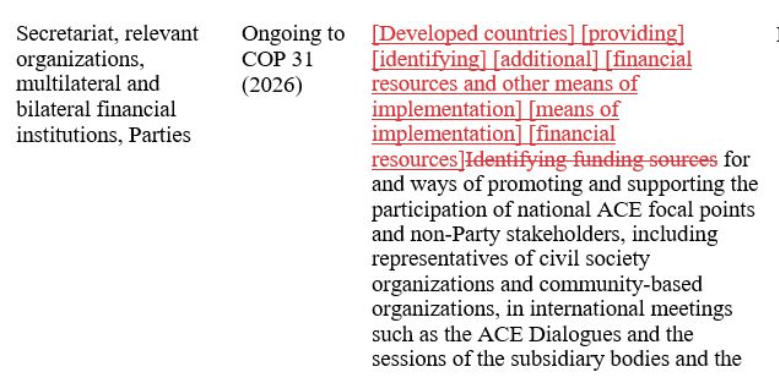

An example of parties at COP negotiations going through texts and debating on the wording chosen. Some discussions on a few words can take hours. Photo: Supplied.

Often at negotiations – where some rooms are quiet and comfortable – parties can debate for hours on a single word or phrase to be included in a decision text. The irrelevant, minute details are so focused on, the party representatives can lose their focus of the bigger picture and the real critical demands beyond the walls of their meeting rooms.

Progress is slow, and there is a clear [dis]connection to the outside world and a lack of urgency to help countries which are already suffering devastating impacts due to the climate crisis.

(I am writing “[dis]connection” in the format negotiators use when deciding on how to word agreement texts).

Apart from the lack of urgency, there is also a [dis]connection between the narratives portrayed in the pavilions and through the protests of civil society and those discussed in the negotiation rooms.

At the Pakistan Pavilion – in mourning after devastating floods in August caused the deaths of over 1,700 people and impacted 33 million – the simple yet powerful texts of “The Lost and The Damaged – Pakistan’s Climate Catastrophe” and “What goes on in Pakistan Won’t Stay in Pakistan” provoked grief and heartbreak among many participants of COP.

The Pakistan Pavilion at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in November 2022. Photo: Chin Chin Lam.

Through various protests and demonstrations at COP27, the cries of civil society echoed throughout the venue. The voices of marginalised indigenous communities, whose livelihoods and cultures are deeply connected to and dependent on nature, were among the loudest last year.

The demands from the next generation were equally roaring, greatly enabled by the first-ever Children and Youth Pavilion at COP27. Yet the urgency of those calls for rapid climate action was not reflected in the negotiation rooms.

As witnessed at COP27 last year – and from personal experience – people are more likely to take real ambitious action while experiencing the impact of the climate crisis first-hand. The plethora of youth climate leaders I met at COP27, including Marciely Ayap Tupari from the Brazilian indigenous community of the Amazon Forest, and Salote Nasalo of Fiji, were determined to lead climate action after witnessing their own homes severely affected by the crisis.

I am also reminded of the record-breaking extreme heat Hong Kong witnessed last summer, sitting in my room without an air-conditioner (to reduce my carbon footprint) suffering from heat exhaustion, and determined to advocate for more temporary heat shelters in Sham Shui Po.

All the while feeling frustrated with the lack of climate adaptation and resilience policy and action in Hong Kong, further amplifying the risks for vulnerable groups – such as residents of subdivided units, the elderly, people experiencing homelessness, or outdoor workers – who are already suffering from the consequences of extreme heat caused by climate change.

A street cleaner. File photo: Lea Mok/HKFP.

Therefore, it is crucial to amplify the voices of civil society at COP, and enable them to have a greater say in high-level negotiations at the conference. This is important to bridge the gap between the currently [dis]connected negotiations and the people who are beyond the walls of the meeting rooms, in hopes of forming more ambitious climate actions and decisions.

There is great power in empathy, a core value of the design-thinking process which is essential to identify the best solutions.

Empathy can be gained through experiencing the consequences of climate change through storytelling, strong imagery or words, and demands echoed by civil society from around the world. It is something that the Pakistan Pavilion, countless protests and youth leaders successfully delivered at COP27, despite most not having a seat at the negotiation tables. The power of people and their efforts must be continued for COP28 next year.

COP28 will be held in Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, and will conclude the first global stocktake of the Paris Agreement. The global stocktake is a two-year process that happens every five years, and is essential to assess, collectively, the progress of the implementation of the Paris Agreement and address opportunities for enhanced action. COP28 is assumed to be more mitigation focused, as countries review their carbon reduction progress.

Global Day of Action Protest at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, on November 12, 2022. Photo: Chin Chin Lam.

Civil society will continue to share stories, make voices heard, and demand global leaders and negotiators not only to better represent marginalised communities already suffering from the climate crisis, but also, to apply pressure for faster and bolder action.

With the success of the first-ever Children and Youth Pavilion at COP27, COP28 should expect the voices of the next generation who are protecting their future to be even louder. This was also reflected by the Minister of Climate Change and Environment of the United Arab Emirates, Ms Mariam bint Mohammed Almheiri, who expressed her desire to expand youth participation in the COP proceedings.

To also bridge the gap between the [dis]connection of Hong Kong to the international climate conference, it is hoped that Hong Kong will officially send delegates, especially youth delegates to participate in next year’s COP28.

Furthermore, it is hoped the city will take much more ambitious climate action to keep the goal of the Paris Agreement – 1.5 degrees – alive, and to ensure that citizens and local communities have the capacity and adequate infrastructure to adapt to the extreme weather events and climate disasters that are already happening.

Featured image by UN (Flickr)

This article first appeared on Hong Kong Free Press (HKFP) and is republished here as part of an editorial partnership with Earth.Org.

—

About the Author:

Chin Chin Lam is an urban planner and a youth climate advocate who is determined to transform Hong Kong and other cities worldwide into sustainable developments. Her passion extends outside of her professional work, and she is actively involved with several youth-led, professional, and non-governmental organisations such as YOUNGO, the Youth Constituency of the UNFCCC, Hong Kong Institute of Planners, WalkDVRC and CarbonCare InnoLab.

Chin Chin is also the founder of the Community Climate Resilience Concern Group, which advocates for better climate adaptation facilities for residents of inadequate housing, and the founder of social media platform Urban Acupuncture Hong Kong, which aims to push the agenda of sustainable urbanism to the next generation of city shapers.