- Population (2019): 51 709 098 (28th most populated country).

- GDP per capita (2019): USD$31 762 (Ranked 29th globally).

- Emissions (2018): 673 Mt (12th highest emitter).

- Earth.Org Sustainability Index Ranking: 112th.

Pledges & Targets

- Paris Agreement & NDC: South Korea’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), last updated in October 2021, targets the following:

-

-

- To reduce GHG emissions by 40% by 2030 compared to 2018 levels.

- Ending all overseas coal financing.

-

- Road to Net-Zero: In October 2020, South Korean President Moon Jae-in announced the country will commit to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050.

- Clean Energy Goals: South Korea has set out a 42% renewable energy target for 2034, up from renewables’ less than 6% share of the country’s energy mix in 2020. The country aims to generate 30% of its energy from renewable sources by 2030.

State of Affairs

South Korea’s largest challenge lies in how to rapidly decarbonise its electricity sector. In 2020, renewable energy made up less than 6% of the country’s energy mix, while fossil fuels accounted for 86%. Alarmingly, coal still supplied 40% of the country’s energy needs. Considering South Korea’s wealth and capacity for innovation, the country could aspire to be much more aggressive in decarbonising its economy and expanding its capacity for renewable energy.

South Korea’s president, Moon Jae-in, announced a substantive multibillion-dollar Green New Deal in 2020 that would include investments in green infrastructure, clean energy and electric vehicles. In addition to ending overseas public financing for coal production, the plan would introduce a national carbon tax, create new urban forests, expand and strengthen the country’s recycling infrastructure and establish a stronger foundation for new installations of renewable energy. While this legislation is promising, in its current form it would reduce South Korea’s emissions by only 12.3 million tonnes of CO2 over the next five years, which would be decidedly insufficient.

To move forward, South Korea will need to combine a reevaluated and highly ambitious Green New Deal with an equally ambitious NDC compatible with the Paris Agreement’s goals. The government is expected to announce this new NDC before COP26, and the hope is that it will begin to chart a pathway for South Korea, among the few developed countries so heavily reliant on fossil fuels, to decarbonise its economy.

Climate Vulnerability & Readiness

The ND-GAIN Country Index by the University of Notre Dame summarises a country’s vulnerability to climate change and other global challenges in combination with its readiness to improve resilience. The more vulnerable a country is, the lower their vulnerability score, while the more ready a country is to improve its resilience, the higher its readiness score will be, on a scale between 0 and 1. South Korea’s scores are:

- Vulnerability: 0.36 (ranks 50th out of 192 countries).

- Readiness: 0.73 (ranks 8th out of 192 countries).

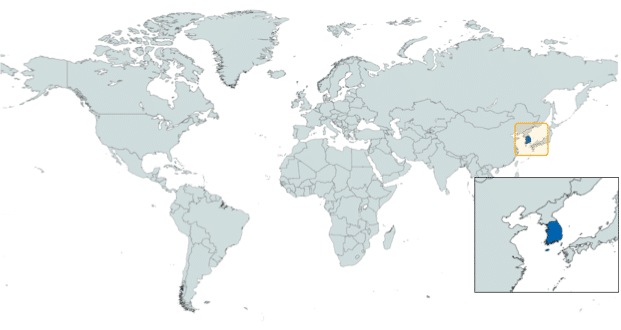

South Korea, the world’s 3rd most densely populated country, with a population of 486 persons per km2, contains one land border to the north and is otherwise surrounded by seas. Per the World Bank, climate change impacts will primarily be felt through floods, storms, landslides and epidemics. Nevertheless, South Korea is regarded to have comparatively high readiness and resilience, given its economic wealth.

South Korea occupies the southern end of the Korean peninsula, spilling out from Asia into the Pacific Ocean. The country is particularly vulnerable to flooding, storms and sea level rise. Between 2007 and 2016, natural disasters incurred KRW 3.4 trillion in economic losses due to disrupted commercial activities (almost USD$2.9 billion), and cost the government about 7.1 trillion KRW in restoration after natural disasters. In addition, rainfall-induced landslides are a frequent occurrence throughout the country. During the 2011 rainy period, there were 58 deaths and 200 injuries caused by heavy rainfall and subsequent landslides. Looking forward, sea level rise also presents a serious threat, as rising waters will contribute to a KRW7.5 trillion economic loss and trigger even more critical floods, storms and landslides by 2100.

The service industry in South Korea accounted for more than 50% of the country’s GDP from 2010 to 2020. Given how reliant its economy is on services, South Korea will also be vulnerable to climate change impacts that make the country less comfortable to visit and work in, such as heat waves. Between 2011 and 2020, South Korea had a record 14 days of extreme heat each year, up from 10.1 days recorded between 1973 and 2020. Higher rates of extreme heat harm local economies and businesses by disrupting services and spending, and also have harmful effects on public health, sending more than 2200 people to the hospital due to heatstroke in 2018. Warming temperatures have also hit the fishing industry hard by raising the ocean’s temperature surrounding the Korean peninsula, increasing seafood prices by up to 40% in 2018.

Environmental Policies by Sector

Energy

- Renewables made up 2.8 % of South Korea’s total energy share in 2017, per IRENA.

- Between 2012 and 2017, the share of renewable energy in South Korea’s renewable energy supply grew by 105.6%.

- In 2017, fossil fuels accounted for 85% of South Korea’s energy production. Non-renewable low-carbon options including nuclear accounted for 16%.

South Korea, ranked as the ninth-largest energy consumer in 2019, has historically relied heavily on fossil fuels, which at the time accounted for about 87% of its energy mix. Still, the Korean government decided to continue investing in new petrochemical facilities through the mid-2020s to raise the share of liquefied petroleum gas used within the country’s energy mix in the following years. While fossil fuels are continuing to receive investments, South Korean President Moon Jae-in has promised to promote renewable energy and move away from nuclear and coal power. As a result, the country is targeting a renewable energy share of 42% by 2034, up from 6.5% in 2020. To achieve this goal, the government plans to shut down at least 30 coal-fired power plants and replace them with renewable energy generation facilities with a capacity of 77.8 gigawatts by 2034.

Transportation

- Vehicle registration in South Korea was about 0.5 cars per capita in 2020, up from 0.36 in 2010.

- Per IRENA, transportation accounted for 12% of South Korea’s renewable energy use in 2017.

- In 2016, South Korea recorded about 65,000 new registered electric vehicles.

Per governmental statistics, South Korea’s population is highly concentrated in the north, which is home to the highly populated urban centres of Gyeonggi and Seoul and about 44.3% of the country’s population in 2019. Along with its economic rise, South Korea experienced rapid population growth as well as individual incomes, resulting in a tremendous increase in private vehicle ownership. To solve the challenges of high traffic congestion and tailpipe emissions, the government has reformed the public transport system in major cities. Seoul, for instance, boasts an enviable public transport network that accounted for 65.1% of all transportation in the city in 2011.

Korea is well known for having one of the largest and most modern transit networks in the world. Within the country’s largest cities, most residents rely on subways as their main mode of transportation, which are known for being fast, punctual and convenient. Seoul, the capital, possessed 18 subway lines in 2020 that connected the city with its major suburbs, and also boasted several intra-city connections to other major cities including Busan, Daegu, Gwangju and Daejeon. For longer distances, trains remain a preferable option for most. The train network in Korea connects most cities and regions across the country with travel times generally within a few hours. The Korean government aims to increase green transportation options, including public transit, cycling and walking, from 70% in 2010 to 80% by 2030, and reduce the transportation emissions of citizens from 0.5 tonnes per capita in 2010 to 0.3 tonnes per capita by 2030.

South Korea is also aiming to be a major force in the EV industry, by investing heavily in research and development of battery technologies. With an investment of KRW40.6 trillion in 2021 to support key battery developers, such as LG and Samsung, the government aims to provide domestic competition to neighbouring China, which possesses the fastest growing EV market in the world. The South Korean electric vehicle push involves the country’s major tech and automotive industries. Electronics giant LG invested USD$4.5 billion in 2021 to set up another factory to produce EV batteries, and Hyundai is planning to increase its EV sales from 100,000 in 2020 to as much as 560,000 by 2025, largely through the introduction of 12 new EV models that target a diverse group of consumers.

Biodiversity

- 16.97% of South Korea’s territorial spaces are protected, as are 2.46% of marine areas, per the NGO Protected Planet.

- Per the Yale Environmental Performance Index, 81.41% of South Korea’s population is urbanised.

- Yale EPI ranked South Korea 39th in the world in terms of ecosystem vitality, which measures how well countries preserve, protect, and enhance their ecosystems and the services they provide.

- Per Global Forest Watch, South Korea possessed 4.38 million hectares of natural forest in 2010, extending over 51% of its land area. By 2020, it had lost 15.1 thousand hectares of natural forest.

The Natural Environment Conservation Act of 1991, South Korea’s foundational environmental protection law, was published to define the term “conservation of natural environment” and emphasise a sustainable utilisation of natural resources. In 1981, the government introduced an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) model to hold countries accountable for environmental impacts and to assist in sustainable growth planning. The executive entity of all these acts is the Ministry of Environment. In 1997, Korea launched its first National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plan (NBSA), a legally binding strategy reviewed and edited every five years to ensure sustainable use of the country’s natural resources. The NBSA is an instrument to achieve the targets set out by Korea as part of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), a global agreement on environmental protection.

South Korea’s latest submission to the CBD was in 2018, and outlined targets to strengthen the education of biodiversity protection and integrate the idea into the public’s daily activities. The government also aims to manage threats to biodiversity, mitigate natural habitat loss, reduce pressure on ecosystems and expand and restore habitats while promoting genetic diversity. South Korea also plans to achieve more sustainable agricultural, forestry and fishery systems. Finally, the government plans to lay the groundwork to make use of scientific knowledge and propose more policies to strengthen cooperation internationally.

Wildlife

- Per the global NGO Earth’s Endangered Creatures, South Korea possesses 81 endangered species, of which 3 are plant species and 78 are animal species.

- Per the research group Animal Protection Index, South Korea has enshrined into federal law legislation that recognises the sentience of animal species.

The main legal provision for animal protection is the Animal Protection Act, first implemented in 2017, which has since been progressively improved upon to ensure animal welfare protection. The act was the first in the country to recognise that animals can feel pain and suffering. The act is managed by an animal welfare committee operating under the oversight of the Ministry of Agriculture. However, implementation of these provisions are not always consistent. The Ministry of Agriculture’s brief only protects farm animals, while wildlife and marine animals do not enjoy nearly as many provisions. The responsibilities for protecting wildlife and reducing animal testing is shifted to other entities such as the Ministry of Environment and Ministry for Food and Drugs, whose mandates do not prioritise animal welfare.

Pollution

- Per IQAir, in 2020 South Korea averaged 19.5µg/m³ (micrograms of air pollutants per cubic metre of air), ranking 41th out of the 106 countries and territories where data was collected.

- South Korea has 1 times PM2.5 concentration higher than the WHO exposure recommendation. This implies that South Korea residents are living in a place with relatively poor air quality.

- In 2018, South Korea had on average 1.06 kilograms of waste per capita daily.

In 2019, the air quality of South Korea was recognised as merely moderate, with its PM2.5 concentration being twice as high as the recommended level. By the end of 2020, the condition had slightly improved and was rated as “Good”, however, this drawdown of particulate pollutant matter may be mostly attributable to the global lowering of air pollution during the COVID-19 pandemic, numbers which have since returned to previous highs.

During winter and spring, the air quality of South Korea is the worst owing to the fine dust blown down from China. Airborne particulate matter was as high as 129 μg per m³ in March 2019, mostly due to this seasonal form of air pollution. Other than seasonal pollution, the key contributors to airborne pollutants are emissions from burning fossil fuels and driving oil-powered vehicles. The number of vehicles has surged since the 1980s, alongside the country’s economic growth. In 2019, about 25% of Seoul’s particulate matter came from vehicles and tailpipe emissions.