The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (the “Montreal Protocol”) is an international treaty which aims to protect the Earth from ozone depletion. The Former United Nations Secretary General, Kofi Annan, contended the Protocol to be not only “the most successful environmental treaty in history”, but also “perhaps the most successful international agreement to date” of any kind.

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

What is the Montreal Protocol?

Objectives of the Protocol

The Montreal Protocol is the first treaty that regulates the production and consumption of nearly 100 ozone depleting chemicals, mainly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). The Protocol was adopted on 15 September 1987 which bound all 197 United Nations Member States. It aims to regulate the progress in a stepwise manner by creating different timetables for developed and developing countries. The parties to the Protocol agreed to cut chlorofluorocarbons by 50% over 12 years, but they swiftly accelerated the reduction to 75% by 1992, and then 100% by 1998.

The Montreal Amendment

Today, we have replaced CFCs with Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) which are gases widely used in refrigeration, air-conditioning and foam applications. While they pose a much lower threat to the ozone layer, some are very potent greenhouse gases, like HCFC-22 with a global warming potential (GWP) of 1,760 that of CO2 on a hundred year scale. Thus, HCFCs are also on a phase-out schedule: developed countries aim for 2020 and developing countries for 2030.

The Kigali Amendment

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are similar compounds to HCFCs , but their lack of chlorine atoms makes them harmless to ozone, yet their GWPs remain thousands of times higher than that of CO2. To support the timely phase out of CFCs and HCFCs, the Parties to the Protocol ratified the Kigali agreement on January 1st 2019, promising to reduce the use of HFCs by 80% over the next 30 years.

Assessing the Protocol’s Success

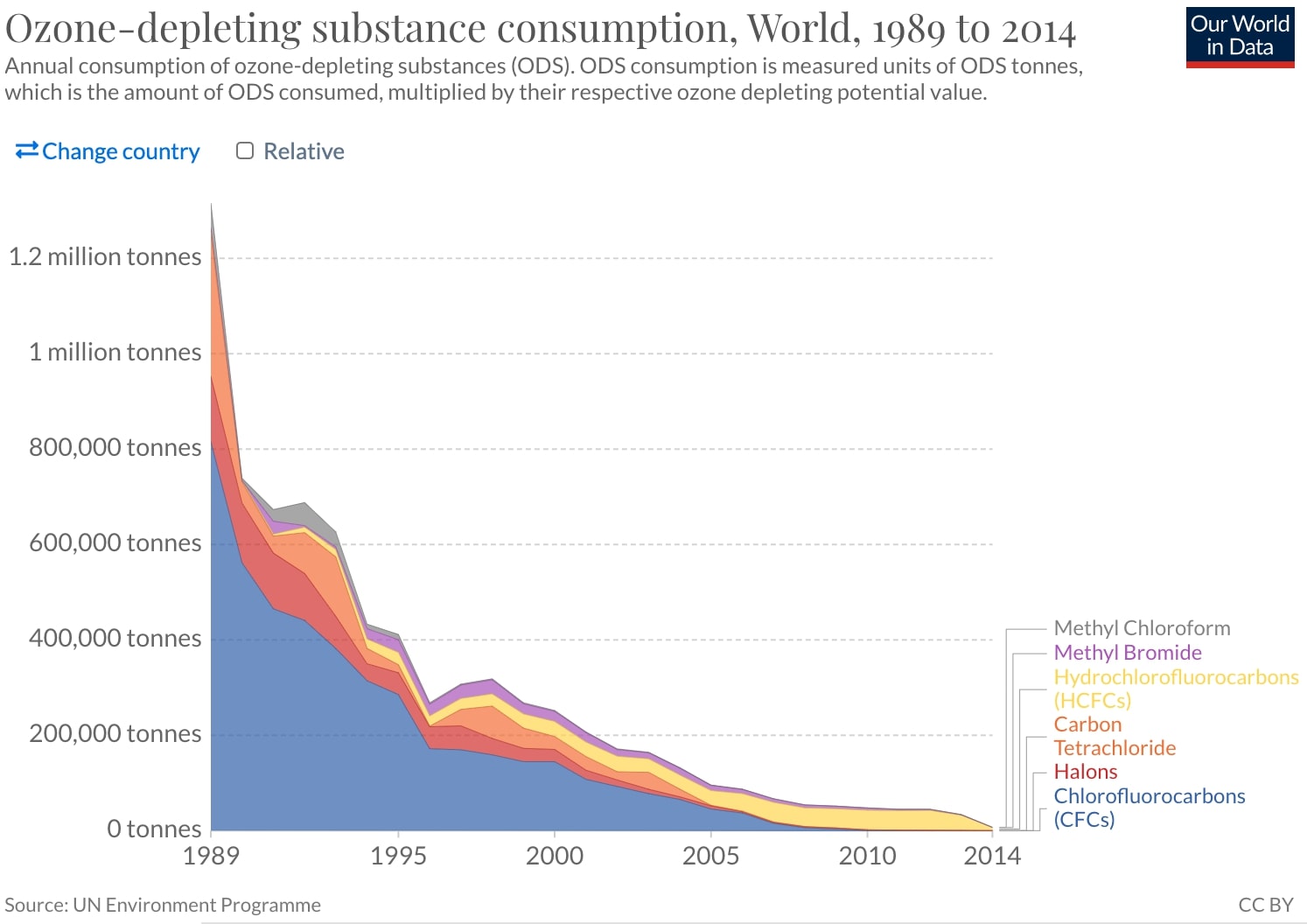

Since 1989, the consumption level of CFCs has attained a sharp drop from 815,613 tonnes to merely 156 tonnes in 2014. HCFC levels have declined from 12,435 tonnes to 6473 tonnes in 2014. The global emissions of ozone-depleting substances overall has plummeted from 1.46 million tonnes in 1988 to 320,000 tonnes in 2014.

Source: Our World in Data

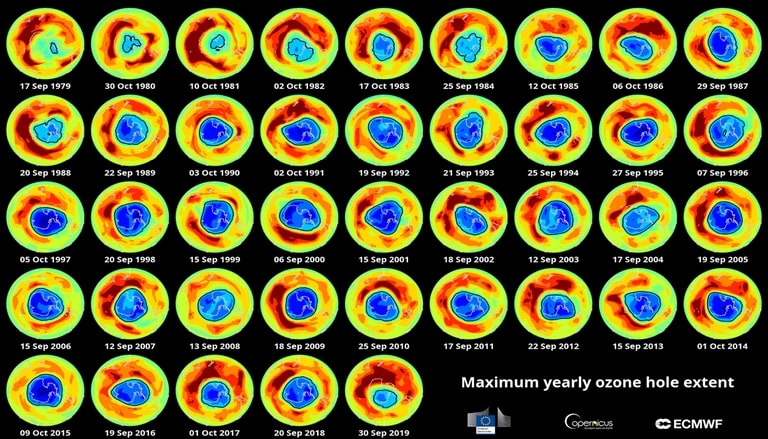

In 2019, the ozone hole is the smallest on record since its discovery. However, NOAA Climate.gov explained that 2019’s small ozone hole was simply the result of an isolated weather event, not part of a trend.

Source: European Environmental Agency, Maximum ozone hole extent over the southern hemisphere, from 1979 to 2019. The blue colours indicate lower ozone columns, while yellow and red indicate higher ozone columns.

Nevertheless, the European Space Agency predicted that the recovery of the ozone hole will continue over the coming years. In the 2018 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion, data reveals that the ozone layer in the stratosphere, the second layer of the atmosphere, has recovered at a rate of 1-3% per decade since 2000. At these projected rates, the Northern Hemisphere and mid-latitude ozone is predicted to recover by around 2030, followed by the Southern Hemisphere around 2050, and polar regions by 2060.. It is estimated that it saves around 2 million people a year from skin cancer.

The Montreal Protocol represents an international success, but this stems from the relatively small number of chemicals to regulate across few industries. Today’s need to phase out all greenhouse gases will require new precedents in international cooperation, which will hopefully occur before our backs are against the wall.

This article was written by Jennie Wong.

You might also like: Are We Getting Over Coal?

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)