The bushmeat crisis refers to the increasingly widespread practice of harvesting meat from locally available wild animals, mainly in Africa, Amazonia and Southeast Asia. This type of hunting often targets vulnerable species and is a huge threat to biodiversity in tropical regions of the world. Additionally, it poses a threat to food security in the long-term as people come to rely on this unsustainable source of food.

—

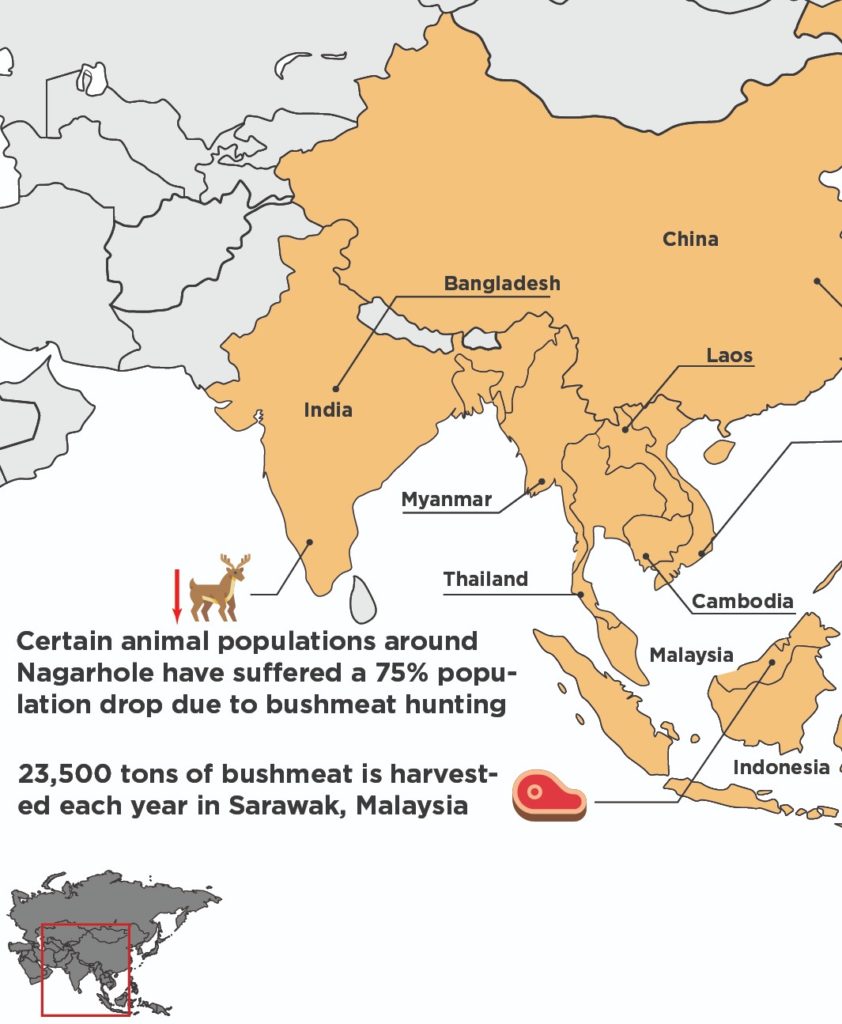

The complete picture of bushmeat hunting in Asia is very cloudy as data only exists for a few places in the region. Nevertheless, we know that over 400 terrestrial species are hunted for bushmeat in South and Southeast Asia. Because most large animal populations have already declined, the main targets are small bodied mammals, like bats and rodents. The result is that Indonesia and the Philippines have 37 and 14 endemic threatened species respectively. These disturbances have ripple effects in their ecosystems, disrupting food chains and even pollination (bats are important pollinators).

Similarly to Africa, tens of millions in Asia depend on bushmeat as a protein source, particularly in rural areas. The biggest driver of excessive hunting is population growth in remote and often forested areas.

The average population density in the Southeast Asian forested areas is 121 persons / km2, versus the 24 persons / km2 in African and Amazonian tropical forests. With this comes deforestation, settlements and their related infrastructure, and farmland accretion. Combined with hunting, there is an enormous amount of pressure being put on the local biodiversity.

It is important to note that economic development is driving down the need, and therefore demand for bushmeat as an essential protein source. Nevertheless, bushmeat is considered as a luxury product in certain cities, thus maintaining a certain level of demand. In Chinese and Vietnamese markets, significant quantities of bushmeat products remain available for non-essential consumption.

In India the hunting trade is generally illegal except for certain indigenous tribes. Overall, its conservation efforts have led to a significant reduction in large mammal consumption. However, bushmeat practices continue among other forest dwelling communities due to population pressure and food security motivations. Cultural practices, like traditional medicine, also drive people to hunt certain animals illegally.

China’s case is different. The population barely relies on bushmeat for sustenance – it is rather international wildlife trade and traditional medicine that keep the practice alive. Some people attribute extreme health benefits to often rare animal products which gravely threaten specific species like pangolins and rhinos. This has led to the extinction of numerous species, both in China and abroad. Their large and influential market is a huge contributor to the global bushmeat crisis. Further, handling massive amounts of unregulated animal products greatly increases the risk of zoonotic pathogen spread. Many are aware that the current Covid-19 outbreak is likely to have commenced in the Huanan wholesale seafood market in Wuhan. Since then, China has strengthened restrictions on animal trade, although no complete bans have been imposed.

The takeaway: bushmeat hunting is endangering medium-sized mammals (mostly because there aren’t enough large ones left to hunt), and also increasing the risk of zoonotic disease. Legislation can be implemented to halt harvesting for non-essential consumption, but the lack of information is a barrier. Diligent research is scarce and difficult to conduct because of the illegal nature of bushmeat hunting, therefore involving potentially dangerous networks.

The second cause is less complex, but just as difficult to address. Many depend on bushmeat for sustenance, and until these people’s lack of resources is resolved, the practice will continue.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern. Mapping by Simon Papai.

You might also like: Bushmeat Hunting in South America

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)