As climate change slowly transforms the world’s weather, so does the suitability range of crops. There are big questions surrounding the future of food, including how we will feed over 9 billion people by the end of the century, so we take a look at a facet of the problem here.

—

When carbon dioxide’s atmospheric warming properties were first discovered in Sweden in 1896, it was broadly seen as a good thing. Why not? Sweden is a cold country, and a little extra warmth could benefit both the people’s mood and their agriculture.

Over a century later, we are sitting in the midst of a rapidly changing climate whose warming has a myriad of knock-on effects. While it is clear that the overall effect is negative, especially for those in harsh, under-developed countries, some consequences might be more nuanced.

Crops in particular are a hot topic. Many studies have looked at the adverse effects of climate change on crop yields, but according to Lindsey Sloat, a researcher at the Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability at Colorado State University, they overlooked an important factor. Crops will suffer in their current layout, but suitability will actually shift.

What does this mean? This means that climate-induced losses can be mitigated and even overcome by migrating our crops to newly suitable areas. Crop migration is already in full swing; some areas of Sicily, Italy have become too hot for their perennial grapevines, pushing farmers to grow more exotic fruit like avocado and passion fruit.

Unfortunately, physically moving to follow a particular plant’s growing range isn’t realistic in today’s world. Farmers will therefore be limited to a new selection of crops once conditions have changed, regardless of local demand, resources and endemic plant diseases.

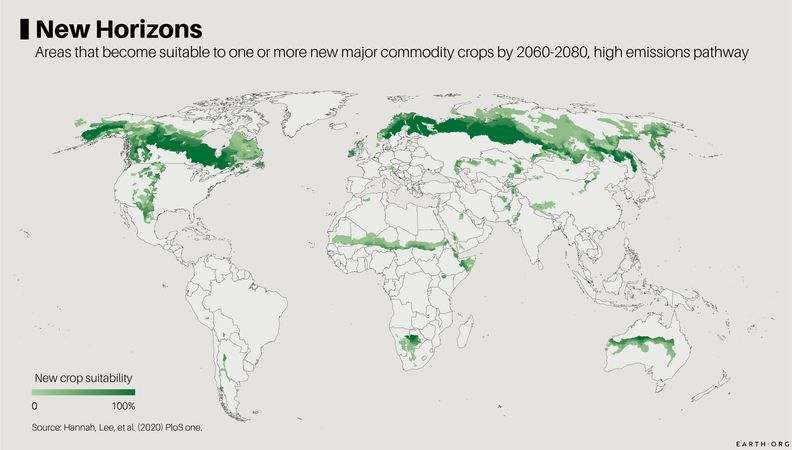

Lee Hannah and a team of researchers from Conservation International, Virginia, USA, modelled the extent of climate-shifted agricultural frontiers in a high emissions scenario.

These new frontiers are equivalent to over 30% of the current agricultural land on earth. Investing in them would mean a massive disturbance of biodiversity, water resources and ground carbon.

Watersheds serving over 1.8 billion people would be affected, diverted for irrigation or contaminated with fertilizers and pesticides. The scale of change induced by climate change is huge, and the cost of adaptation just as daunting.

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)