Why this Metric?

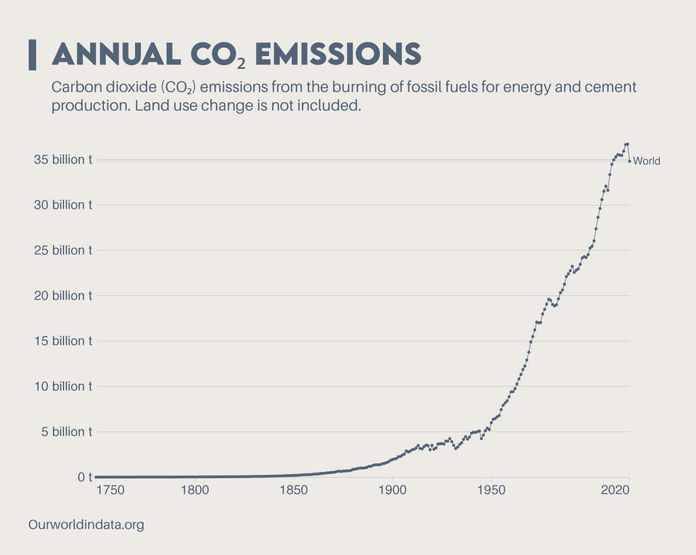

Humans have been releasing greenhouse gases for thousands of years. Driven by the emergence of agriculture, small-scale deforestation and fires contributed comparatively insignificant amounts to what we generate today. The discovery of fossil fuels multiplied the amount of energy we could use and deploy, catalysing the exponential development of our society over the past two centuries.

Despite early warnings from scientists such Svante Arrhenius, CO2’s warming potential was long ignored, but the evidence is now indisputable. Climate change is occurring and we are causing it through excessive greenhouse gas emissions.

Exploring the Metric

What it lacks in heat-trapping potential, CO2 makes up for in sheer quantity, which has led it to produce 75% of observed global warming. Other greenhouse gases might be more powerful, but are either shorter-lived or in trace amounts. Thus, CO2 has become the standard: we speak of mixed greenhouse gases in CO2 equivalent (or CO2e), and its warming potential over 100 years (also standard) is 1.

In light of its outsized influence, we’ve naturally made CO2 the main target of emission-reducing strategies. In doing so, other gases like methane have been neglected, which research has shown might make better targets for short-term results. This is because methane, whose 100-year warming potential is 28 to 36, actually only has a ~15 year lifespan. Its “true” warming potential is better measured over 20 years, where it gets up to 82.

Most methane emissions come from unintentional leaks and lack of attention. Limiting these could yield significant results in the short-term, making it easier to stay under critical warming thresholds.

Where the numbers come from

The data was provided by the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm that generates annual CO2-equivalent estimates for all greenhouse gases by analyzing sector and country-level economic data.

Future Outlook

What might seem simple in principle, i.e. phasing out emissions until reaching net-zero, is actually incredibly complex. Huge societal transitions entail winners and losers, and the losers in the quest for sustainability would be the fossil fuel industry. Its enormous influence allows it to stall policy, while its established infrastructure makes it essential to developing countries growth.

International cooperation could go a long way. Rich countries pledged to give USD 100 billion to poor countries to help them adapt to climate change, which could have given them more liberty to pursue sustainable pathways, but the pledge was broken. Net-zero pledges have been made but are liable to be broken, and even if honored won’t be enough to avoid potential catastrophe.

The good news is that science is coming to the rescue. Satellite technology allows us to monitor our planet like never before, detecting and measuring things like methane leaks and illegal deforestation. It’s also shown that methane is a viable and possibly better target than CO2 at the moment. We urgently need to narrow the gap between science and policy, and have a long hard think about how much we want to protect the fossil fuel industry.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

Check out our other indices here.

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)