This year, people have been battling one of the most severe locust infestations in recent history from East Africa to China. COVID-19 is exacerbating the problem, hampering preventive measures, while scientists suspect climate change may be helping the locusts to proliferate.

—

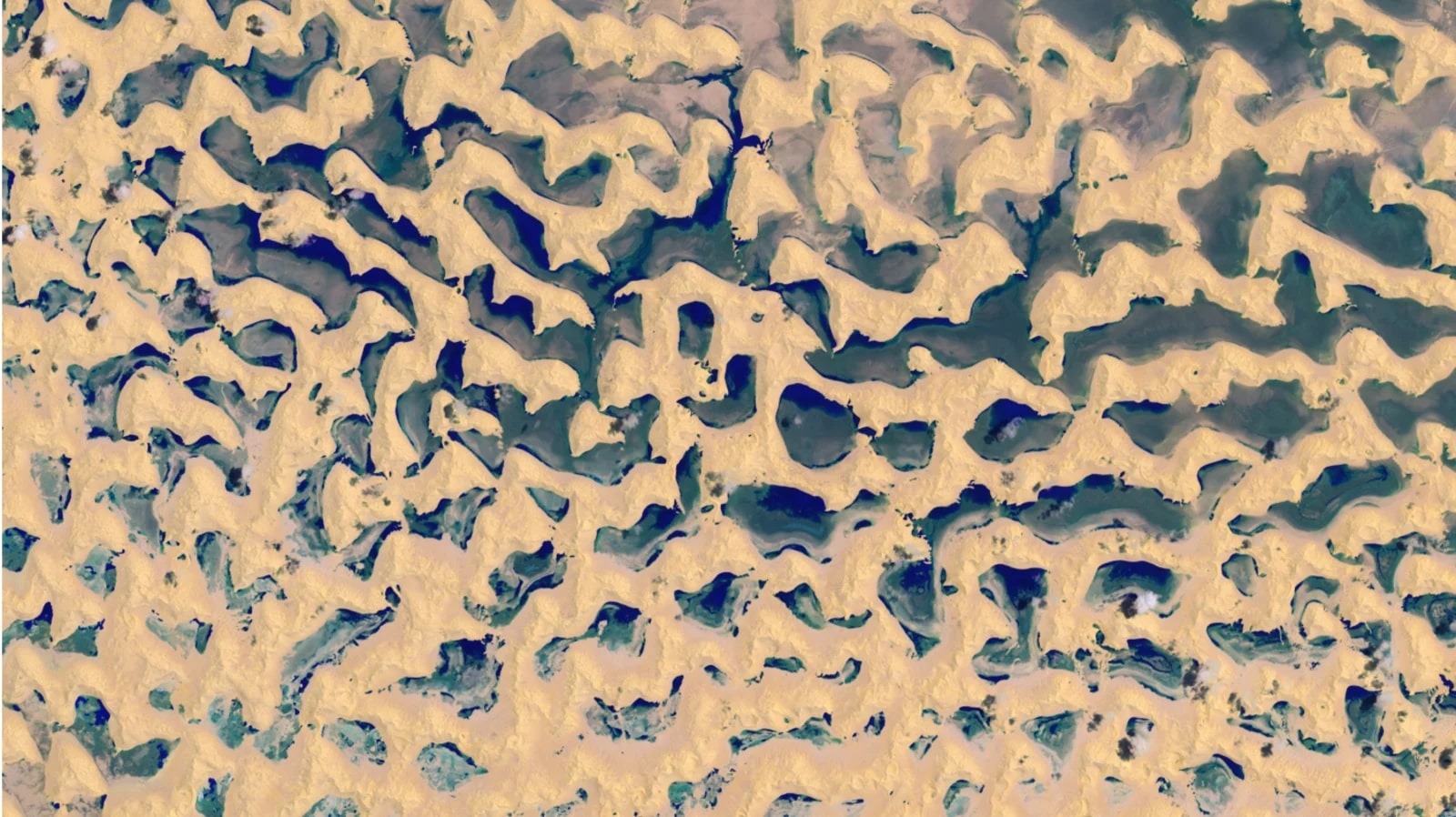

The desert locust, or Schistocerca gregaria, is always present in the deserts between Mauritania and India. Usually solitary, they can switch to a single mass behaviour when concentrated in high numbers. Extreme weather events, notably heavy rainfall, increase the chance of a locust swarm forming; rain provides moist soil for the insects to lay their eggs in, and allows vegetation to grow and provide shelter and food.

Satellite image of Rub’al Khali, days after Cyclone Mekunu made landfall in 2018. Lakes formed in between sand dunes, allowing some plants to grow, which fuelled the proliferation of desert locusts. (Photo by Lauren Dauphin via NASA Earth Observatory).

Lack of food can also drive relatively small groups to form an outbreak that is usually contained within 5000km2. If left unchecked, these can evolve into an upsurge, especially if rain has created favorable conditions in the surrounding regions. If the swarm grows enough to affect two or more regions at once, it is upgraded to a plague which can cover up to 512,000km2 (largest swarm recorded, US Midwest, 1875).

From the Biblical plagues of Egypt to the resurgence of locusts in 2020, these creatures are nothing to scoff at. When roused, a swarm can cover over a hundred kilometers per day, with each little locust eating its own bodyweight in leaves shoots, fruits, flowers, seeds, stems and barks. Needless to say, the wasteland they leave behind is quite bleak.

The Damage

Eastern Africa, the Middle-East and parts of Pakistan and India have long relied on large-scale use of pesticides to deal with locust swarms, but this all came to an abrupt pause when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Flight restrictions, suspensions and cancellations meant the delayed shipment of pesticides used to deal with the desert locusts. As pesticides ran short, and locust surveillance efforts were hindered, food security became an ever-growing issue, not just for the affected nations, but also the regional food supply chains already under strain by the coronavirus food crisis.

The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) has estimated that millions more people will struggle to feed their families, and the World Bank estimated that 90 million hectares of agricultural land are at risk, and that damages in the near future could number in the billions of dollars. The FAO suggested that containing the plague will cost at least US $138 million, but will balloon in cost the longer the locust plague goes undealt.

This year, afflicted countries are suffering the worst outbreaks in decades which begs the question:has climate change got anything to do with it?

Locusts and Climate Change

The unusually heavy rains that hit the East African region are linked to a climatological system named the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). Much like El Niño, this system has three phases (positive, neutral and negative), and the positive phase causes heavy rainfall and storm activity between eastern Africa and India. The IOD’s positive phase lasted from June to December in 2019 and caused more rain than it had in 40 years, leading to massive swarm formation. Moreover, the subsequent winter season was mild, allowing the swarms to persist through to 2020.

It is difficult to be sure, but scientists believe that global warming is amplifying the effects of the IOD.

Monthly Indian Ocean Dipole mode index from January 1979 to December 2019. Credit: NOAA.

The graph above shows the fluctuations in ocean temperatures between the eatern and western parts of the Indian Ocean, a proxy for measuring the IOD. As we can see, this year’s positive IOD has had a longer-lasting, higher-amplitude swing.

Scientists managed to look as far back as the year 1240, and found that positive phases of the IOD were once rare, whereas they are now common and increasing in frequency. Further studies show that this frequency could increase three-fold by 2099 compared to the 20th century.

There is pretty solid evidence that climate change is at least partly to blame for the unexpected resurgence of locust swarms. Authorities would do best to consider this a “new normal” and plan accordingly.

This article was written by Javier Chai Rui Cheng and Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: Geoengineering: What is BECCS?

References

-

Reliefweb.int: https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/desert-locust-situation-update-2-september-2020

-

al-Harbi, M., 2020. Saudi Arabia’s Empty Quarter Now ‘Full’ with Lakes After Cyclone Mekunu. [online] Al Arabiya English. Available at: https://english.alarabiya.net/en/features/2018/05/29/Saudi-Arabia-s-Empty-Quarter-now-full-with-lakes-after-Cyclone-Mekunu.html [Accessed 30 August 2020].

-

Aljazeera.com. 2020. Alarm as Coronavirus Curbs Disrupt East Africa Fight on Locusts. [online] Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/alarm-coronavirus-curbs-disrupt-east-africa-fight-locusts-200403173558211.html [Accessed 30 August 2020]

-

Njagi, D., 2020. The Biblical Locust Plagues of 2020. [online] BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200806-the-biblical-east-african-locust-plagues-of-2020 [Accessed 30 August 2020].

-

Stone, M., 2020. A Plague of Locusts Has Descended on East Africa. Climate Change May Be to Blame. [online] National Geographic. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/02/locust-plague-climate-science-east-africa/ [Accessed 30 August 2020].

-

World Bank. 2020. The Desert Locust Crisis and The World Bank Group. [online] Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/the-world-bank-group-and-the-desert-locust-outbreak [Accessed 30 August 2020].

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)