Deforestation in Spain dates back to ancient cultures, starting from the final period of the Stone Age with the expansion of agriculture. Throughout the centuries, Spain was drastically deforested but it was not until the 20th century that the urgent need for forest protection and regeneration was properly tackled by the government. By 1982, nearly 3 million hectares of previously barren lands had been reforested. However, too many of these reforestation efforts have chosen non-native pines and eucalyptus as the species to be planted – which can increase the risk of forest fires and, in turn, desertification.

—

The History of Deforestation in Spain

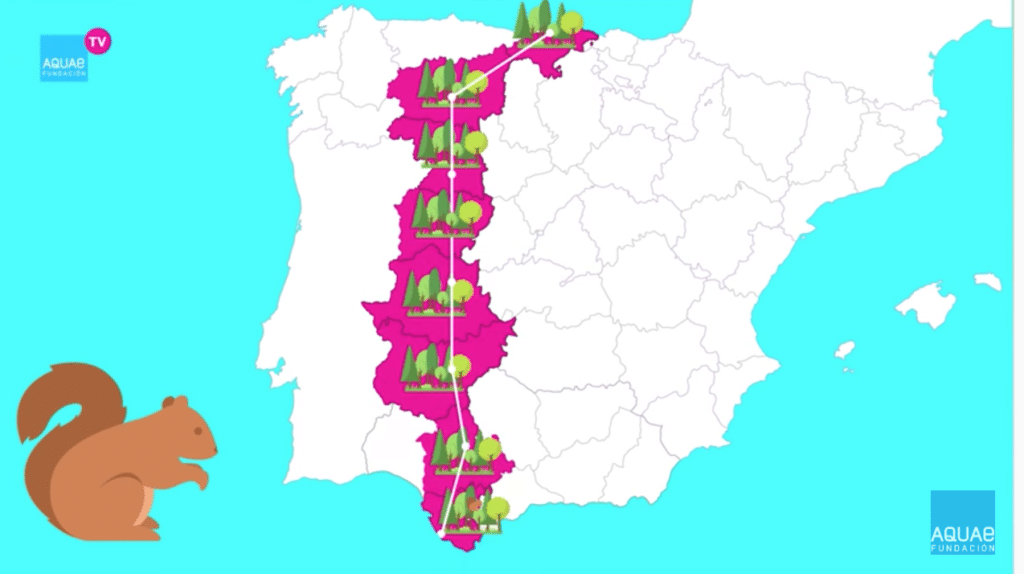

According to a popular legend dating back to the 1st Century, the Greek geographer Strabo described the Iberian Peninsula (where Spain is located) as so lush that a squirrel could cross it from South to North (“from Gibraltar to the Pyrenees”) by jumping from one tree to the other without touching the ground – which would be impossible today. Although the claim is contested and it seems that Strabo never said such a thing, the truth is that since the expansion of agriculture during the Neolithic Period (10000–4500 BC), the Spanish landscape has been greatly deforested. This section, largely based on this paper by María Valbuena-Carabaña et. al., will offer a glimpse into how this happened.

Deforestation in the Iberian Peninsula began centuries before Spain had its name. The factors responsible were wars and invasions; cultivation; fires followed by grazing; and industry and mines. The first to suffer were coastal pine forests along the Mediterranean shores: as the most available sources of timber and pitch (resin) for shipbuilding, they were hugely affected by the expansion of commercial sea routes. By the beginning of the Christian Era (the period beginning with the year of Christ’s birth), only remote mountain forests were safe, since transporting the timber was incredibly difficult back then.

With the expansion of agriculture, forests were transformed into cultivated and grazing areas, resulting in significant changes in the landscape. The first farmers used recurrent fires to clear the forest vegetation. This gave a selective advantage to species adapted to natural fires, and led to, for example, the replacement of the local Maritime pinewoods by Evergreen oaks. As Eastern Mediterranean cultures such as the Romans started colonising the area, the agricultural strain on the ecosystem only grew.

During the Bronze and Iron Ages (3300 to 1200 BC and 1200 to 600 B.C., respectively) mining became popular. As warfare became more important, the use of metal for mainly military use led to a constant demand for charcoal. Mining built on the depletion of forests that was started by agriculture, creating both direct and indirect impacts on forests. Even so, during the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the start of the Early Middle Ages (late 5th and early 6th century AD), there was still a considerable amount of woodland in the peninsula.

From 711 to 756 AD, Arabic culture took over the Iberian Peninsula. During this time, their advanced irrigation techniques allowed for an improved use of the land, and the geographer El Idrisi described a region where woodlands provided vital resources, praised the timber quality and regretted deforestation in Spain. However, the Christian Reconquest (which lasted from 722 to 1492 AD), was fatal for the land: as every part of the Iberian Peninsula was at some point the border between the Moor and Christian Kingdoms, malicious tree cutting and fires drastically diminished the forests that formerly covered the area. By the 13th century, the Christian Kingdoms had almost completed their expansion all the way to the south of the peninsula. They exploited vast, forested and depopulated areas through cattle herding (mainly sheep). This linked the Spanish economy to the worldwide trade of wool, which led to even more drastic deforestation.

Vague and Failed Deforestation Regulations in Spain

It was in the 13th and 14th century that the Castilian government finally recognised the importance of forests in the rural economy, and developed strict regulations aimed at conserving the resources. Ironically, however, because the cattle sector was protected by the crown, it continued to thrive (merino fine wool trade was bringing increased economic profits).

Then, as members of the Bourbon dynasty aimed to protect the commercial routes between mainland Spain and the Spanish colonies in America, the importance of the Spanish Navy grew along with the interest for timber. Two Forest Ordinances passed in 1748, with the main objective of forbidding the cutting of trees marked by and for the Navy. This permitted the Navy to cut more trees than they required, to keep the best and largest, and to pointlessly ruin forests because of lack of knowledge and care. The Ordinances were restrictive and unfair, and as peasants refused to accept them, illegal deforestation in Spain became common.

Afterwards, during the first part of the 19th century, liberal and absolutist regimes alternated in power, and the forest policies varied with each political shift. By the mid-19th century, the demand for Spanish wool fell, and in 1855, a critical event happened: the Minister of Finance, Pascual Madoz, promoted the disentailment law, basically putting public forests on sale. In 1859, a catalogue that classified public forests was completed, permitting the sale of 10,872 woods covering around 3.4 million hectares. Thankfully, the few existing forest engineers managed to add a clause which excluded forests whose sale was considered not appropriate by the government. They were able to keep a total of 19,774 forests (6.76 million hectares), from being privatised.

Between 1855 and 1924, 260,000 private landowners obtained 5.2 million hectares (more than 10% of Spain’s area). In about a century, nearly 18.5 million hectares of land were privatised. Unfortunately (although perhaps predictably) the process failed to accomplish the expected conservation results: many private forests were turned to pastures or arable land for instant profit.

You might also like: 10 Deforestation Facts You Should Know About

Reforestation Programmes in Spain

By the 20th century, deforestation in Spain had drastically altered its landscapes and regeneration was urgent. Between 1901 and 1939, reforestation was promoted for water management purposes, as well as to prevent landslides. Regions that were reforested during this time are established forests today, distributed across Spain, from the Pyrenees to the Mediterranean coast.

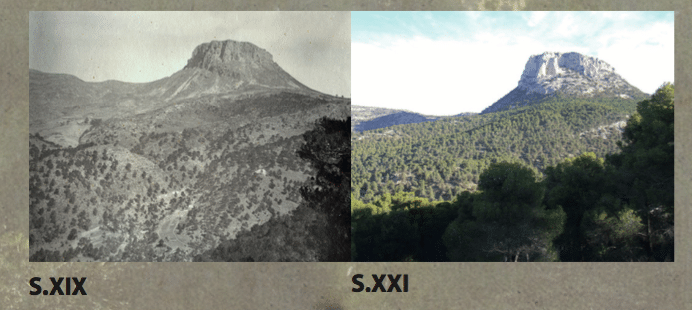

A great example of how reforestations transformed the landscape during this period is Sierra de Espuña (Murcia, Spain). By the end of the 19th century, it was desert-like, deprived of vegetation and would suffer from destructive floods. But by 1917, following the reforestation campaign, it was a green area teamed with biodiversity richness, and it was included in the Catalogue of National Parks.

During the dictatorship (1940-1975) that followed the Spanish Civil War, there was an ambitious reforestation plan, as it was considered an appropriate solution for unemployment. The General Plan for the Reforestation of Spain, published in 1939, recognised the rising productivity of forests over time and aimed to conserve and restore all terrains suitable for reforestation. This led to the reforestation of 2.9 million hectares (11.34% of the Spanish forest surface).

Since 1984, Spain has undergone many social and institutional changes, in addition to joining the European Union. During this time, a good initiative was the common agricultural policy, which provided financial assistance to landowners who planted trees in cultivated land. However, there have been no consistent criteria to assign new forested areas, making statistics hard to interpret and leading to conflictive data. For instance, some statistics indicate that Spain had gained 33% in forest area between 1990 and 2020. However, other sources show a 46% decrease in annually reforested land.

In addition, while almost every regional government has approved a Forest Plan that complies with the EU Forestry Strategies and the Habitat directive, a lack of coordination among administrations has failed to achieve a more integrated strategy towards reforestation.

Forest Fires and Danger of Desertification

Although the reforestation efforts described above have generally had a positive effect, there’s a few issues with the way in which the Spanish have reforested the land. To start with, the species that were mostly used were (often non-native) pines and eucalyptus. Without taking into account the historical transformation of natural ecosystems, this reforestation effort could be problematic. As explained by Moya Navarro et. al., “the Iberian Peninsula cannot be simply filled with trees. In the diversity of Iberian ecosystems we find many valuable but non-forested ecosystems, which are worthy of maintaining, conserving and improving. They provide biodiversity that would be degraded by introducing species that are not adapted to these areas, as would be the case of woodland or changing this type of vegetation.” They go on to point out that planting trees wherever and however is not a good idea. Rather, “a good starting point would be to begin to properly manage the existing forests, instead of thinking of planting new ones in every treeless area”.

Proper management of existing forests is indeed urgent, as one fifth of the land in Spain is currently at risk of turning into deserts, and 31.5% is already affected by desertification. This is due to an increased rate of forest fires, caused partly by a higher average temperature and less rainfall. Fires destroy the topsoil, provoking erosion and ultimately desertification.

If reforestation is not done correctly, it increases the risk of “mega” forest fires. This is because if all the trees and plants are the same age, the same size, and grow more densely together, dead wood and organic matter accumulate, creating ideal kindling for fire, and letting it spread further.

Therefore, as stated by Valbuena-Carabaña et. al., “plant conservation strategies should take into consideration the degree of alteration our ecosystems have suffered and the historical causes of such modifications”. This is important to understand before taking part in citizen efforts which, although driven by good intentions, often lack scientific criteria and can thus put the environment at risk.

To help with forest management, European countries have reintroduced the bison, which is considered a keystone species, meaning it plays a distinct ecological role in shaping the landscape it inhabits. The bison helps create bare soil patches, which allows pioneer plants to move in. It also disperses nutrients and seeds across the territory. In Spain, private landowners have started reintroducing the bison to enclosed National Parks and private lands, as a more sustainable approach to land management and nature and species conservation.

Although deforestation in Spain and society’s use of natural resources has deeply impacted the country’s landscape , a lot of it has been successfully reforested in the last century. Today, Spain is the third country in Europe with the most forest cover (18.4 million hectares, about 36.7% of the country). In fact, Enrique Segovia, the director of WWF Spain, goes back to Strabo’s famous squirrel and claims that it could now cross Spain from North to South, but only on the west.

Segovia goes on to point out that some trees (Sabinares specifically) might be too far apart for a squirrel. However, as noted above, this should not lead to planting more trees between them, as understanding the landscapes (along with the historical changes they have been through) is vital for successful conservation. If Spain manages to refine their approach to restoration in this way, they could even be a model for other countries that wish to make large scale reforestation efforts.

You might also like: Replanting Monoculture Plantations Are Not Reforestation Projects

Featured image by: Pixabay