Yves Saint Laurent once said that while ‘fashion fades, style is eternal’. If only it were so simple.

Earth.Org takes a look at the data on fast fashion’s persistent water pollution.

—

Photo by Ciara Kavanagh, , Small Boutique Fashion Week.

Whether you court couture or stun in street style, New York Fashion Week 2021 was the talk of the town.

Running September 8th-12th, this season’s exposé of exclusive designer content was a bold return to business. As the rag trade bounces back from the pandemic, sustainability seems to be at the core of fashion’s future. The Council of Fashion Designers of America, longtime NYFW architect, launched landmark reports, ‘Sustainability by Design’, and ‘Playbook for Positive Change’, to coincide with the occasion, detailing efforts at reducing carbon emissions, plastic waste, and transport inefficiencies. Growing consumer demand means designers from the highstreet to the heftiest names in the business are taking the long view on fashion’s intersection with expression, economics and our Earth.

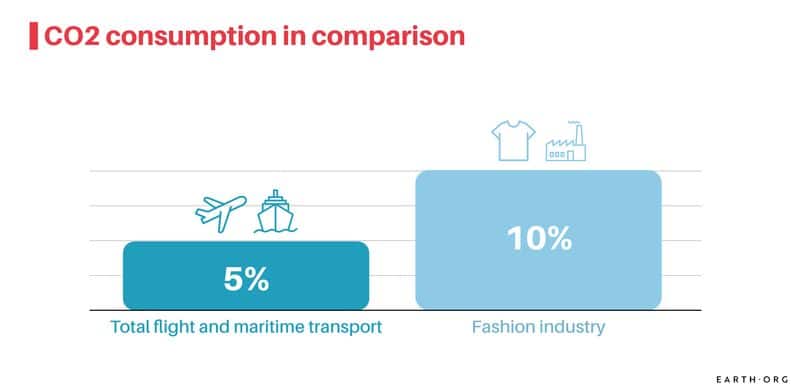

The ecologically minded can breathe a sigh of relief; a more conscious approach to fashion is long overdue. Textile production has skyrocketed in the last 10 years, outpacing environmental regulation across the board, with the fashion industry responsible for a sizable chunk of textile-related carbon, which accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions overall. That’s not to mention the growing menace of microplastics, and the mountains of last season’s landfill. The sustainable innovations at this week’s sartorial soirées certainly tend to these concerns, focusing on timeless pieces, androgynous style and honouring heirlooms.

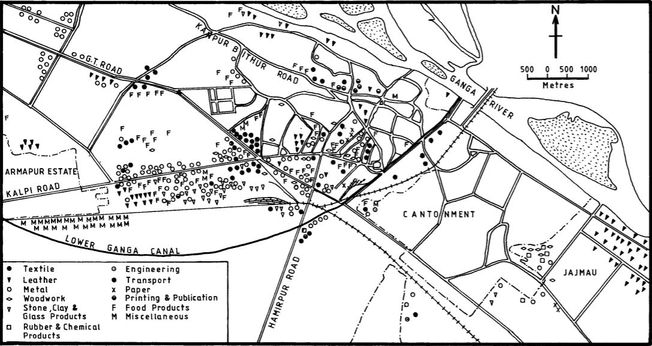

But where does this leave those at the coalface? To focus solely on emissions or textile waste alone overlooks a critical public health and environmental concern: production itself. Alarming studies reveal that fast fashion is slowly poisoning workers at the source. With more than 20% of global wastewater flowing from fabric factories, the case of Kanpur– a booming leather hub in Uttar Pradesh, northern India– is far from anomalous. There, more than 400 textile workshops on the banks of the Ganga readily release industrial wastewater into the sacred river, polluting local water supplies needed for drinking, irrigation and everyday sanitation. Monitoring stations set up downstream by the Central Pollution Control Board register more than 598 million litres of untreated sewage flowing out of Kanpur daily. The (mostly untreated) industrial sewage carries heavy metals like chromium, copper and zinc, and toxic PAHs (poly-cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) out of the factories and into the river as it surges toward the Bay of Bengal; but not before it makes a stop in local crops, daily hygiene, and even dinner plates.

A map of Kanpur’s many textile workshops (indicated with black dots). Many more have sprung up since 2000.

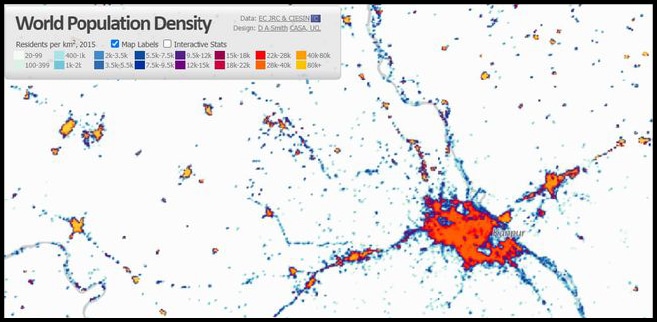

When we say Kanpur is a booming hub, we do not only mean in regard to its industries. It is also very densely populated, which puts many in danger of chemical poisoning.

This map of population density shows the high concentration of dwellings in central Kanpur. The area represented in the industry map above is indicated in the oval.

A recent study of Ganga River samples taken in Kanpur found concentrations of Chromium, Iron and Copper so high that the water, used for crops and cooking, is deemed unsafe for humans to even bathe in. Traces have also been found across tubers, fruits and leafy vegetables growing close to polluted groundwater or irrigated from the river. Given the high population density on the threshold of the production districts, the contaminated water is the obvious choice. In some cases, the heavy metal content far exceeds the limits set by the Bureau of Indian Standards, limiting local consumers to a dangerous fate.

Far surpassing safe levels, the chemicals contained in local food bioaccumulate in the liver, stomach and intestines, leading to an array of cancers. Fatal diseases like renal tumours, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, extensive kidney lesions, osteoporosis, cancer, and nervous system issues are the tip of the iceberg. What’s more, infant mortality is inextricably linked to an accessible supply of clean water in the early years, and data from the region attests to the link between local industrial activity and high infant mortality. A high cost for the price of a cheap jacket.

The human cost of unchecked industrial pollution is well documented- closer to New York, the Flint Water Crisis and Dupont pollution scandal spring to mind. Tannery pollution in Kanpur shines but another spotlight on environmental racism, with the interconnected issues of pollution, climate change and habitat loss predominantly affecting those in the global South- often poor, female, black people and people of colour.

The heightened scrutiny of environmental racism and fast fashion alike is just about beginning to bear fruit, though the road ahead is long. Some ethical names are mainstreaming clean production (check out GoodOnYou.com for data on how people, planet and animals fare from spool to store). More than 220 brands have signed the Bangladesh Accord, legislation advocating for the safety and protection of garment workers following the tragic collapse of Rana Plaza factory that blew the lid off the working conditions that Primark, Mango, and J.C. Penney sign off on.

Granted, the haute couture on New York’s runways is hand-crafted far from the fumes of industrial cities. But as for the trends inspired by the extravaganza, many of which will reach our stores in weeks, much more damage remains to be done with every click ‘buy’.

Though we might like to agree with Yves Saint Laurent, reinventing ourselves every time H&M drops a new collab, nothing fades when it comes to chronic illness and the slow poison of unmet human needs. Sustainable Development Goal #6 calls for safe drinking water and sanitation for all, a basic requirement for a healthy life. Until consumers, rich and poor alike, have the option to dress themselves in truly ‘clean’ clothes, the fashion industry will continue to stymie sustainable development as it affects people of all colours and creeds across the globe.

So, next time you catch yourself wondering whether the price of instant noodles is enough to invest in a t-shirt, you might remember Lucy Siegel’s words: fast fashion isn’t free. Someone, somewhere, is paying.

This article was written by Ciara Kavanaugh. Cover photo by freestocks on Unsplash.

You might also like: What is Climate Change?