Hong Kong discards between 4-6 million disposable face masks every day. The bulk of these discarded face masks are sent to the landfill along with the general waste. Based on the estimation that each face mask weighs two to three grams, the face masks disposed of at landfills every day would weigh some 10 to 15 tonnes. However, a significant number end up polluting the environment, including drains, streams, and beaches and end up in the sea. According to the Hong Kong Secretary for the Environment, KS Wong, these face masks are not suitable for recycling. She says, “Since disposable face masks, including N95 masks and surgical masks, are made of composite materials of different kinds and metals which are difficult to be separated, they are not suitable for recycling or discarding in recycling bins to avoid contaminating other recyclables.” How can the world achieve a “zero waste” future?

—

The global figures are approximately 1 000 times more at 15 000 tonnes of masks a day. The bulk of the discarded face masks are either incinerated or sent to the landfill along with municipal solid waste (MSW).

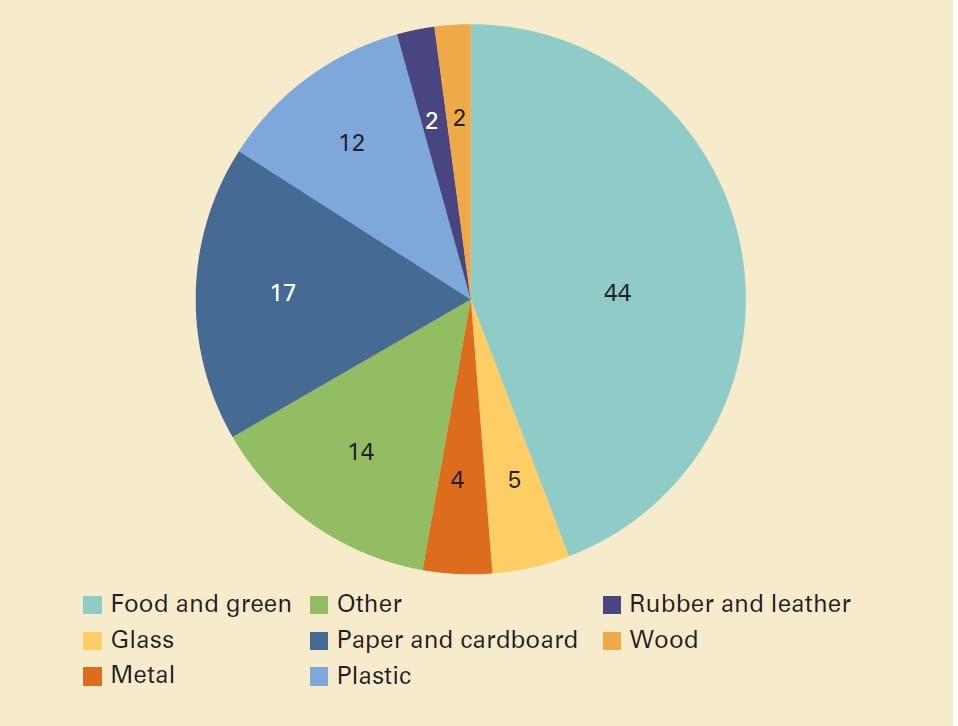

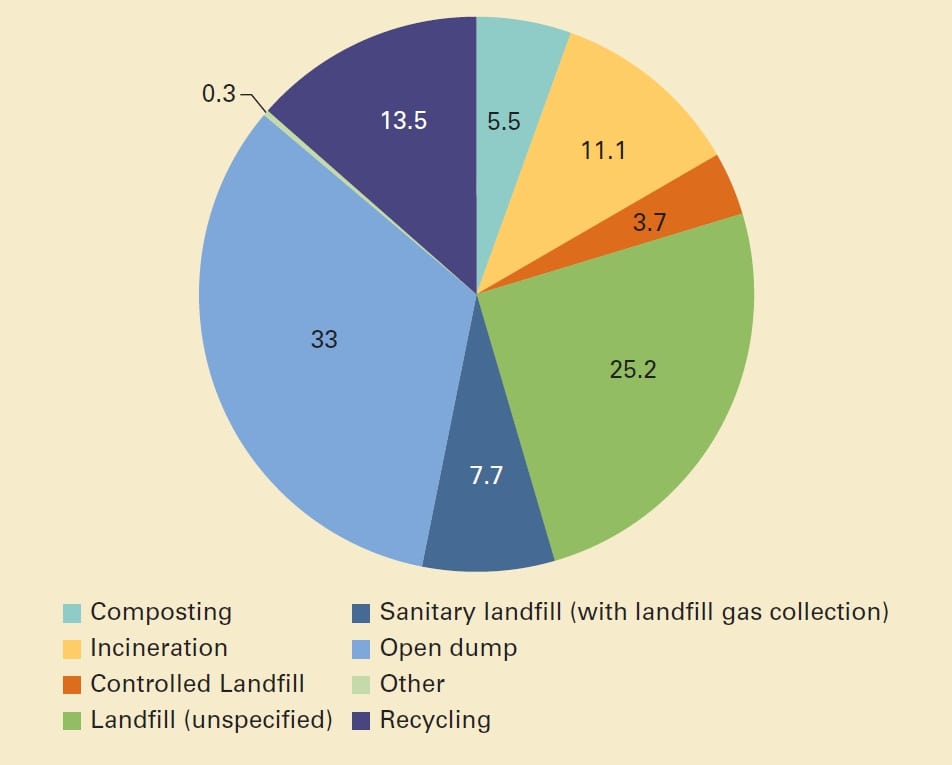

The sustainable management of increasing quantities of wastes such as MSW, Industrial Wastes, Agricultural Wastes, Construction Demolition Waste (CDW) etc, is a global challenge. MSW generation will increase to 3.40 billion metric tonnes by 2050 from around 2.01 billion tonnes currently as per a World Bank report. In 2016, 12% of the world’s MSW was plastic, of which the world produced 242 million tonnes. It is estimated that only 13.5% of today’s waste is recycled and 5.5% is composted.

Plastic waste is choking our oceans, yet our consumption of plastics is only increasing. The COVID-19 pandemic has added significantly to this crisis due to the sudden increase in the consumption of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). An estimated 1.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide–equivalent (CO2-equivalent) greenhouse gas emissions were generated from solid waste in 2016, which is about 5% of global emissions. Without improvements, solid waste-related emissions are anticipated to increase to 2.6 billion tonnes of CO2-equivalent by 2050. 44% of all MSW is food waste (contributing 50% of the GHG emissions from rotting) and 33% of all MSW is disposed of in open dumps and/or burnt.

The global distribution of population compared to the percentage of waste generation shows China and India to be major contributors (together accounting for 36% of the world’s population and 28% share of MSW generation), followed by the USA (4% world’s population contributing 12% of the waste). Such disparities are likely to be further exacerbated by the pandemic. For example, South Asia is one of the hardest-hit regions by the outbreak, with India recording nearly 9.8 million cases. The pandemic outbreak in the South Asia region is not only harming public health through community transmission but is becoming a huge liability in terms of its environmental impact. The healthcare waste management system of the South Asia region is the least developed among the World Health Organization regions.

Delhi, the capital of India, generated about 371 tons of biomedical waste per day in June 2020. This was an increase of 1 400% from May’s 25 tons per day. Uttar Pradesh, the most populated state in India, generated about 247 tons of infectious medical waste per day in July 2020, but was able to safely handle less than 10 tons per day of it. Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, generated 206 tons of biomedical waste daily in July, a steep increase from 3 tons per day before COVID. Similar trends of infectious medical waste generation due to COVID-19 have been observed in other countries of the South Asia region.

While the prospects of a zero waste future may look utopian in light of the above scenario, it is not as difficult as we are made to believe. Hong Kong has performed abysmally against its own target as per the 2013 Government-issued “Hong Kong Blueprint for Sustainable Use of Resources 2013-2022,” which set out a comprehensive strategy to reduce waste and increase recovery and recycling. A recycling fund of HKD$1 billion has not made a significant dent yet and the draft mandatory waste charging scheme proposal that was stuck in the legislative process for almost a decade was recently dumped. However, the experience of neighbouring Taiwan and South Korea is highly encouraging. South Korea adopted a waste charging policy back in 1995 and observed that the overall waste disposal rate dropped by 17% by 2001 and by 40% by the year 2010. The recycling rate increased to 60% in 2010 from about 16% in 1995, and the economic benefits of the recycling industry increased from HK$1.7 billion in 2001 to HK$7 billion in 2009. The “Per Bag Trash Collection Fee” system, adopted from Taipei, has worked well in Seoul, which is now a global model for recycling. This illustrates the fact that modern societies driven by rampant consumerism need to pay for their environmental footprint – be it in the form of a carbon tax or waste charging system. The detrimental effect of our lifestyles driving climate change can only be tamed by such a ‘user pay’ model and implementation of circular economy principles by producers and manufacturers.

For a ‘zero waste’ future to be realised, the first step has to be for policymakers to change their mindsets. Each component of the municipal solid waste stream is recyclable. Food waste and organic matter can be composted, metal, glass, and paper have well-established re-use. Its the waste plastic that has been a big challenge given its volume due to low density and capacity to pollute the environment. While recycling disposable face masks is not easy (nor is plastic waste), it is not impossible. It has been demonstrated that much of such waste plastics can be converted back to fuel oil through catalytic thermal pyrolysis, used in lightweight plastic aggregates for use in concrete, or melted and reshaped into plastic products like bricks, blocks, and plates. Only with such innovative ideas can the world hope to achieve a ‘zero waste’ future.

You might also like: 6 Things the World Must Do to Tackle Climate Change- Lancet

Figure 1.(a) Composition of Municipality Solid Waste and (b) Methods of disposal (Source: Datatopics.worldbank.org).

Figure 2. Share of Global Population against waste generation (Source: recyclinginternational.com).