“Conservation must be reframed as a long-term commitment. Until the community confronts the uncomfortable truth that starting new projects holds no value unless existing ones are sustained, billions of dollars will continue to be spent on initiatives that provide the illusion of progress while nature continues its decline,” writes Ajay Sawant.

—

COP30 has come and gone, leaving behind a familiar mix of new commitments and renewed political promises. But amid the declarations of progress, one issue that received almost backhanded attention is the quiet abandonment of conservation projects after their high-profile launches.

New research published in Nature Ecology & Evolution by a team co-led by Matthew Clark from the University of Sydney’s Thriving Oceans Research Hub shows just how widespread the problem is. Across nine major community-based conservation programs studied in Africa, roughly one-third of participating groups stopped carrying out their conservation responsibilities because implementation simply fell apart. Clark warns that this figure is likely an underestimation, representing only a sliver of a much larger and largely undocumented global pattern.

The scale of this problem is staggering. Between 1892 and 2018, governments around the world collectively undermined legal protections for conservation areas through 3,749 documented events, known as Protected Area Downgrading, Downsizing and Degazettement (PADDD), affecting approximately 2 million square kilometres across 73 countries. To put this in a better perspective, the total area stripped of protections is equivalent to the size of Greenland. Nearly two-thirds of these rollbacks were directly linked to industrial-scale resource extraction, including mining, oil exploration, and large infrastructure projects. But besides the formal and informal withdrawals, one thing that has remained consistent is the existence of these efforts as “ongoing” on papers.

The Financial Mirage

The financial dimensions of such abandonments reveal a clear disconnect between investment rhetoric and long-term commitment.

Globally, conservation spending ranges from $87 billion to $200 billion annually, depending on what activities are counted. And as climate and biodiversity losses intensify, these investments are projected to reach up to $540 billion by 2030 and $740 billion by 2050. Despite this, emerging evidence suggests that over one-third of these initiatives are abandoned within a few years of launch.

Clark notes that the core problem is uncertainty itself. “We have virtually no line of sight on how long these programs endure,” which makes it nearly impossible to design conservation for the decades it requires. He adds that without continuous financing, “the kind that treats conservation like public infrastructure,” projects inevitably stall or disappear once short-term funding cycles end.

When analyzed, these abandonments primarily occurred in locations facing intense land-use pressures or where external funding is uncertain. Often, reliance on short-term donor funding creates a precarious foundation for conservation efforts that require decades, or even perpetuity, to yield meaningful ecological recovery. In the Comoros, for instance, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are almost entirely funded by donors with no government budget allocations. So, when a donor withdrew a planned 1.5 million euro (US$1.76 million) allocation, efforts to establish an Environmental Fund for Protected Areas stalled completely, leaving active conservation projects vulnerable to collapse.

Political Reversals Accelerating the Crisis

Abandonment, besides slow institutional neglect, can also be triggered overnight by political decisions. For instance, in mid-2025, the US government cut more than $300 million from international conservation funding, affecting hundreds of protected areas and conservation initiatives worldwide. Those cuts were accompanied by attempts to remove formal protections from major sites within the country, including the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument and all 18 of California’s national forests.

Subsequent reporting has detailed the far-reaching consequences of such changes. In parts of Africa and Latin America, multi-year grants from the now-defunct US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the US Fish and Wildlife Service worth tens of millions of dollars were cancelled or frozen, leaving NGOs, community groups, and park authorities scrambling to pay rangers, maintain equipment, or even keep basic patrols going. Individual organizations reported losing the majority of their operating budgets for key landscapes when single large grants disappeared. For communities where each conservation job supports up to entire extended families, these abrupt reversals translate directly into lost livelihoods, frayed trust, and pressure to return to extractive activities.

The abandonment study points to a subtler driver: that conservation systems are designed around charismatic funders, not resilient governance. When the figurehead moves on, the project’s foundations move with them. In that context, it is hardly surprising that community groups in Africa, or rights-based fisheries users in Chile, drift away from conservation commitments when the external support and political shield that once sustained them disappear.

Following the precedent, the UK government has also confirmed that it will not contribute to the new Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) proposed by Brazil in the lead-up to COP30, which seeks to raise US$25 billion in public sponsor capital from governments and public institutions, leveraging a further US$100 billion from private finance. Set against the widening fiscal retrenchment among major donors, the UK’s refusal reflects a broader political shift in which countries are increasingly oriented towards unsustainable, announcement-driven models of conservation, one in which the architecture for long-term support erodes even as the stewardship ambition continues to grow.

Why Conservation Accounting Fails

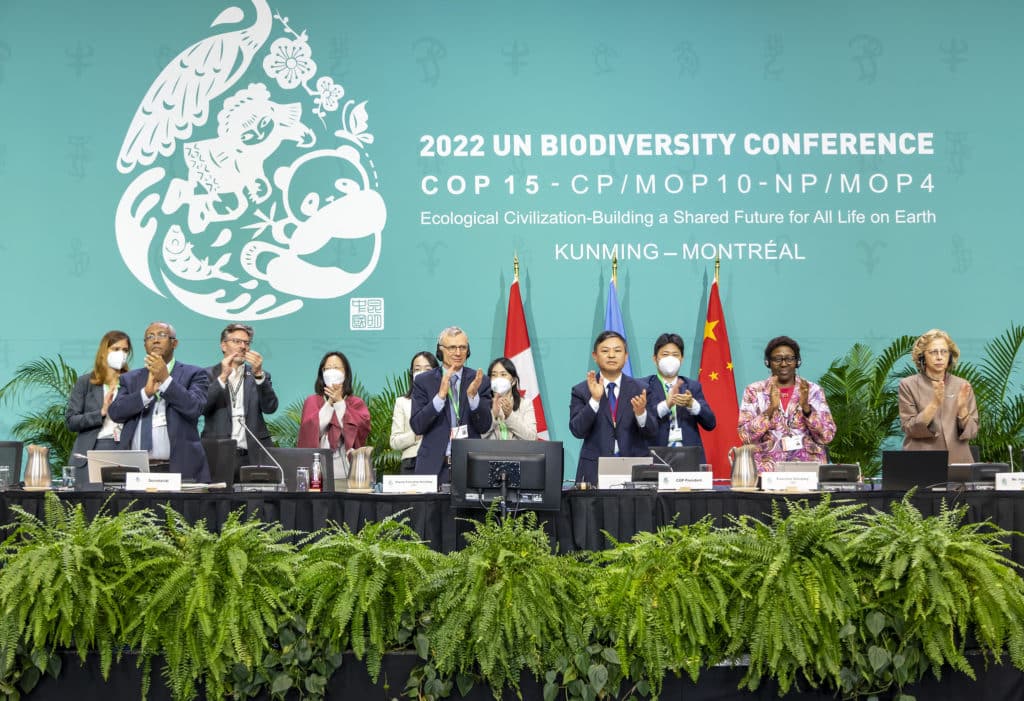

The core problem is in how conservation progress is measured and reported. International biodiversity targets, including the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework goal to protect 30% of land and ocean by 2030, focus almost exclusively on establishing protected areas. But no one is asking if the parks we have established are being managed effectively, or if the projects even still exist in any meaningful way.

Abandoned projects, which are often inactive, are frequently calculated in official reporting, masking the true state of environmental protection and inflating estimates of progress. This failure is particularly concerning for climate change mitigation efforts, where carbon offset credits may be awarded for projects that quietly cease operations, undermining the integrity of carbon markets and climate finance mechanisms.

The lack of monitoring adds another layer to this problem because many conservation programs include only initial monitoring requirements. When reevaluations do occur, the focus is on the direct drivers of biodiversity loss, like land-use change or pollution, while underlying indirect drivers like political instability, competing economic interests, conflicting policies, and insufficient funding are rarely addressed. Expert assessments reveal that biodiversity-damaging subsidies, external economic interests competing with conservation goals, and policies that conflict with biodiversity objectives are major factors explaining the lack of conservation success.

The Way Forward

First, conservation should be judged not only by where it starts, but by how long it lasts. Projects, donors and governments should publish how many initiatives remain active, funded, and enforce their rules five, 10, and 20 years after launch. A marine protected area that slowly loses its manpower and budget after five years, for instance, should not continue to count toward 30×30 targets in the same way as a site that has been effectively managed for decades. Making “time survival” a core metric would immediately change incentives, rewarding organizations to keep their work going.

Second, external conservation funding should come with a binding “exit strategy” that is co-designed and agreed with local communities before a project begins. Too many initiatives often assume that communities will somehow take over once donor money runs out, even when there is no realistic revenue stream, legal authority, or institutional capacity to make that possible. To avoid this, funders should be required to state up front what happens when their grant ends in terms of who pays salaries, who holds legal rights, and what minimum conditions must be in place before responsibilities are handed over. If no credible answer exists, the project should not go ahead in its current form.

Third, conservation needs a cultural shift around failure. At present, very few projects formally report that they have stalled, scaled back, or been abandoned, even though practitioners privately acknowledge this happening. Journals, donors, and governments should create safe channels and incentives to document when and why initiatives end, similar to how medicine and public health now treat program discontinuation as a legitimate research topic. Normalizing this kind of reporting would make it harder to overclaim success and would give practitioners an evidence base on what frequently does and what only occasionally works.

Perhaps most critically, conservation must be reframed as a long-term commitment. Until the community confronts the uncomfortable truth that starting new projects holds no value unless existing ones are sustained, billions of dollars will continue to be spent on initiatives that provide the illusion of progress while nature continues its decline. The crisis is not inevitable. A comprehensive meta-analysis found that conservation interventions improved biodiversity or slowed its decline in 66% of cases compared to taking no action. The challenge is ensuring that today’s investments endure long enough to deliver those results.

Featured image: Marcelo Perez del Carpio/Climate Visuals Countdown.

—

This article was originally published on Mongabay.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us