Every second, an area of seabed the size of a football field is scraped bare by industrial fishing nets. Known as bottom trawling, this method does not just harvest fish; it also razes coral reefs, suffocates ocean biodiversity, and releases carbon stored for centuries beneath the seafloor. Despite mounting scientific evidence of its destruction, this controversial practice continues in much of the world’s oceans, often hidden beneath the waves and political inaction. How did we allow one of the most destructive forms of fishing to become standard practice and why is it so hard to stop?

—

Although seafood is a staple food for billions of people, few are aware that a large portion of it is obtained using bottom trawling, one of the most environmentally harmful fishing techniques ever developed.

Sir David Attenborough‘s recent release, Ocean, has brought unprecedented attention to the destructive impact of bottom-trawling on seabed habitats. Massive industrial nets rip through crucial underwater meadows in one especially terrifying scene that was shot off the coast of Turkey.

Attenborough’s message was unmistakable: we are destroying the seafloor with the same carelessness that caused land-based deforestation. However, unlike the Congo Basin or the Amazon, ocean destruction occurs behind closed doors until now.

What Is Bottom Trawling?

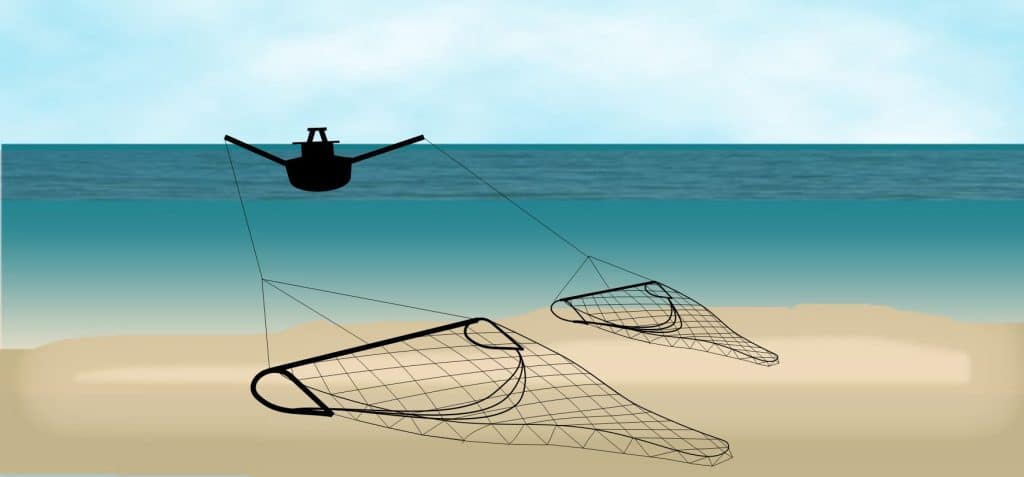

A commercial fishing method, bottom trawling involves dragging big weighted nets along the seafloor to catch fish and seafood that reside close to the bottom, like prawns, haddock, cod and sole. Metal “doors” that plough the seafloor, upsetting everything in their path, hold these nets open.

Bottom trawling is the most popular industrial fishing technique, producing over 30 million metric tonnes of seafood annually worldwide, according to National Geographic.

However, it is also the most damaging. In addition to capturing fish, these nets also capture coral, sponges, sea turtles, sharks, rays, and anything else that gets in their path. According to Greenpeace, up to 92% of the catch in some European waters does not comprise the target species. Dead or dying, these unintended victims are frequently discarded back into the ocean.

Environmental Destruction and Habitat Loss

Bottom trawling does a lot of damage to the environment, and it is usually permanent. A single pass of bottom trawl can destroy structures that took hundreds or even thousands of years to form in fragile ecosystems like coral reefs or sponge fields. Parts of the North Sea and the Atlantic have gone from being complex, biodiverse ecosystems to flat, lifeless wastelands.

Trawling also impacts marine food webs and kills off species already weakened by overfishing and climate change. Predators lose their prey, reef systems fall apart, and fish populations have a hard time bouncing back.

The Carbon Problem: A Hidden Climate Threat

Bottom trawling’s impact extends beyond the marine environment. A landmark study published last year found that dragging nets across the ocean floor disturbs old carbon stores that are buried in sediments. When these sediments are disturbed, they release carbon dioxide – up to 370 million metric tonnes every year, or as much as the whole aviation industry generates in a year.

Scientific studies have shown that 55-60% of the carbon dioxide that comes from disturbed marine sediments gets into the air over between seven and 10 years, warming up the planet. The remaining 40-45% stays in the ocean, worsening ocean acidification and hurting marine ecosystems.

Where Is Bottom Trawling Allowed?

While banned in some areas, bottom trawling is still a common practice around the world, accounting for some 25% of global fish catches. 10 countries, including China, Vietnam, Indonesia, are responsible for roughly 64% of the global bottom trawling catch.

The practice remains widespread also across the high seas – the open ocean lying beyond any nation’s jurisdiction. Here, regional fisheries management organizations often lack the resources or authority to effectively regulate these practices.

United States

More than half of the seafloor in US federal waters is now off-limits to bottom trawling. This is especially true along the West Coast, where important fish habitat designations prohibit trawling across large areas of the Pacific.

Asia

China has put in place a number of restrictions on bottom trawling since the 1950s, but enforcement is lacking. The country still has one of the biggest distant-water fishing fleets in the world, which often operates in international waters, with little oversight.

Vietnam operates the most active fishing fleet in the South China Sea, even surpassing China in some areas. However, due to weak enforcement, the country struggles to monitor its vessels and uphold fishing regulations, resulting in widespread illegal fishing, including repeated incursions into Indonesian waters. Indonesia has responded by detaining and destroying foreign boats to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, but challenges persist as both countries face pressure from declining fish stocks and ongoing maritime disputes.

Africa

West Africa has some of the hardest problems to deal with. Laws in Ghana, Nigeria, and the Ivory Coast prevent foreign trawlers from getting a licence to fish in the country’s exclusive economic zones, which extend as far as 200 nautical miles beyond its territorial seas. However, Chinese trawlers have been able to navigate around this problem by working with local businesses.

Governments in Ghana and the Ivory Coast have tried to respond. Since 2016, they have put seasonal bans on both industrial trawlers and traditional canoes so that fish stocks can recover. But these short-term closures have not stopped the decline of small pelagic fish. At the recent UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France, Ghana announced that it will ban bottom trawling and all industrial fishing from its waters and will double the size of its inshore exclusion zone.

North Africa also has trouble enforcing the law. Artisanal fishers in Tunisia, for example, are having trouble because of widespread illegal bottom trawling, which has led to fewer fish.

Europe

In its 2023 action plan to protect the marine ecosystem, the European Union has mandated the end of bottom trawling activities across all marine protected areas by the decade’s end. However, enforcement is currently weak. Destructive fishing, like bottom trawling, affects 86% of the area set aside by Natura 2000 – a European network of core breeding and resting sites for rare and threatened species, and some rare natural habitat types – to protect marine habitats.

Meanwhile, Norway recently banned bottom trawling near deep-sea coral reefs. But according to a study published in March, Norway remains among the European countries offering the highest subsidies for bottom trawling, along with Italy, Denmark, the UK and Sweden. The total value of the marine life brought onto land via bottom trawling is highest in Norway, followed by Iceland, the UK, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands.

New Zealand

Bottom trawling is a significant commercial fishing method in New Zealand, though its extent is limited and heavily regulated. While remaining the most common method for catching fish and shellfish in the country, efforts are made to manage its impact on the seabed and marine environment. The government has previously stated that “New Zealand is a world leader in successfully managing the effects that bottom trawling has on the seabed, closing one of the largest areas of marine space to bottom trawling in the world.”

Why Does Bottom Trawling Continue?

The primary reason bottom trawling continues is economic inertia. The method is cheap and quite lucrative in terms of catch. Furthermore, governments subsidize the practice heavily. The European Union spends an estimated 1.3 billion euro (US$1.5 billion) on industrial fishing subsidies every year, many of which use bottom trawling. National Geographic says that this method only provides 2% of Europe’s protein. However, contrary to having widespread public support, bottom trawling actually faces significant opposition from European citizens. Recent polling shows that 73% of Europeans support a ban on bottom trawling, with over 250,000 Europeans signing a petition urging the EU to end bottom trawling in marine protected areas.The practice costs European society between €330 million and €11 billion annually, primarily due to CO2 emissions from disturbing seafloor sediment.

In the meantime, enforcement is still very low. According to the Observer, only 38 out of 377 MPAs in the UK are safe from bottom trawling. In 2024 alone, over 20,000 hours of trawling occurred in MPAs, undermining their entire purpose.

The fishing lobby has been vocal in its opposition to bottom trawling bans. In June 2025, the UK government proposed extending the ban on bottom trawling across 41 offshore Marine Protected Areas, expanding coverage from 18,000km² to 48,000km².

The National Federation of Fishermen’s Organisations (NFFO) strongly opposed the ban, arguing that “this ban will cause huge hardship to fishermen and their families” and claiming the government announced it “without any notice to fishermen or their representatives.” The NFFO contends that “trawling does no damage to large parts of those sites” and that the restrictions are unnecessarily broad. The fishing industry responded with frustration to the UK Government proposals, with similar sentiment echoed by French fishermen who called the proposals ‘brutal’.

Despite industry opposition, 80% of UK adults support banning bottom trawling in protected areas, and over 180,000 people from the UK and EU signed a petition calling for an end to the practice.

Public Awareness, Shifting Sentiment and Recovery Progress

Despite this opposition, public awareness is growing. Following the release of Ocean, a Geographical survey showed that 75% of the British public supports banning bottom trawling in MPAs. Many citizens, especially younger generations, have been shocked by the visuals of underwater destruction and have taken to social media to demand change.

David Attenborough, one of the world’s most trusted environmental voices, helped catalyze global awareness about ocean degradation. In his 2025 documentary Ocean with David Attenborough, he warns: ‘We are draining the life from our ocean. Now, we are almost out of time.”

But, he says, there is still hope. Marine ecosystems are recovering in areas where bottom trawling has been prohibited or restricted. Fish stocks in Hawaiian waters have recovered. Scallop populations and kelp forests have started to reappear around the Isle of Arran in Scotland. Whole coral gardens have returned to Alaska, where trawling has been prohibited for more than ten years.

Marine ecosystems are resilient, as demonstrated by these examples, but only if given the opportunity. Although it can take years or even decades, recovery is achievable.

The Path Forward: Solutions That Work

If the international community is serious about ocean conservation, several measures must be implemented:

- Ban bottom trawling in all MPAs. If protected areas are not protected in practice, the concept becomes meaningless.

- Redirect subsidies away from destructive fishing practices and toward sustainable alternatives, such as pole-and-line fishing or trap-based systems.

- Increase transparency in the seafood supply chain. Consumers should be informed of how their fish was caught.

- Invest in surveillance technologies, such as satellite tracking and onboard cameras, to ensure enforcement.

- Expand international treaties and strengthen the powers of RFMOs, particularly in the high seas.

Conclusion

Bottom trawling is a modern-day environmental crisis. It is a choice, not an inevitability made possible by outdated subsidies, poor enforcement, and limited consumer awareness. But it is not too late to reverse course.

Attenborough’s Ocean documentary has brought long-overdue attention to the practice. It has shown the world what bottom trawling looks like and more importantly, what happens when we stop doing it. We’ve seen coral reefs return, fish stocks recover, and marine biodiversity bounce back. The ocean has the power to heal itself but only if we give it space and time.

Banning bottom trawling in protected areas, reforming subsidies, and ensuring transparency in seafood sourcing are essential first steps. The decision is ours to make and the time to act is now.

Featured image: Stephane Lesbats via Wikimedia Commons.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us