From new and expanded protected areas to landmark court rulings, here are some of the policy wins for nature you might have missed in 2025.

—

December is in full swing and, with it, comes the time for reflection. Among countless disasters and endless suffering for those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, stories of progress have also emerged this year. Around the world, governments, civil society organizations and communities made meaningful strides to protect the natural world, preserving precious ecosystems, strengthening legislation and taking destructive industries to court.

Read on to learn about key achievements in nature conservation in 2025.

Expanding Marine Protection

One of the most tangible areas of progress was the expansion and strengthening of marine protected areas (MPAs). This designation grants parts of our seas and oceans with a formal conservation status, allowing ecosystems to recover and thrive. However, not all MPAs are created equal. Some allow certain extractive or destructive activities, while others guarantee full protection of the area, prohibiting any activities that could harm ecosystems.

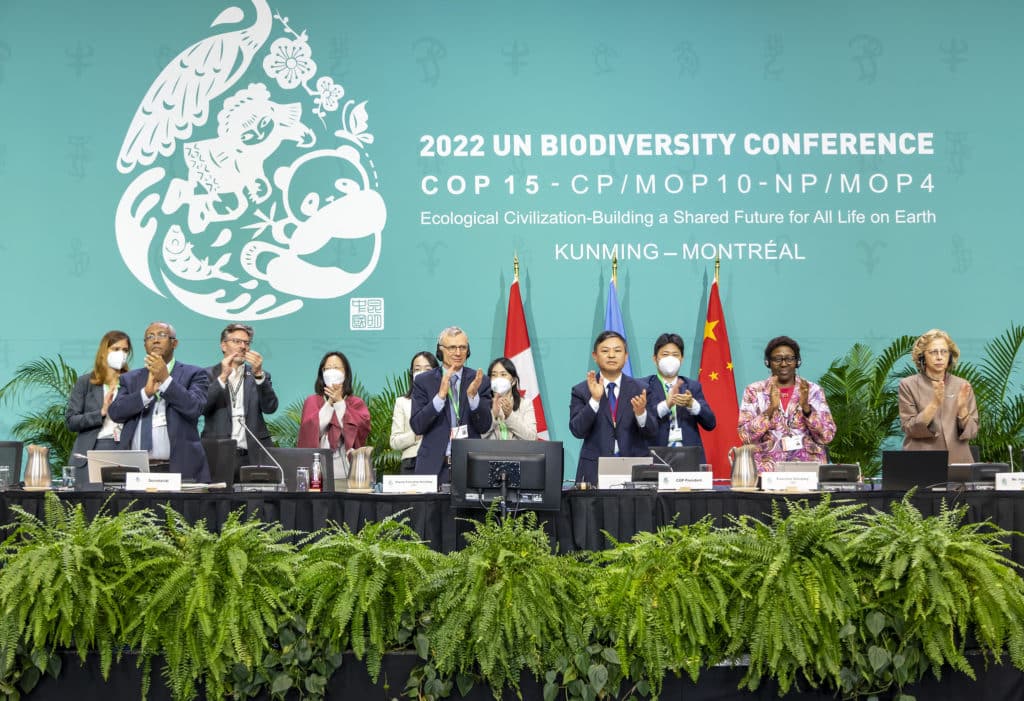

Under the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, countries have pledged to protect and conserve at least 30% of the world’s land and water by 2030 (also known as the “30 by 30” target). Global protection currently falls short of this goal, with only 9.6% of the ocean effectively protected.

However, an important policy breakthrough should change this. In September, Morocco became the 60th country to ratify the High Seas Treaty, meeting the ratification threshold for its entry into force. The treaty establishes a legal framework to create networks of MPAs in international waters – a critical step, given that protecting national waters alone will not be sufficient to meet the 30 by 30 goal.

Against this backdrop, a July study offers compelling evidence that these protections actually work. By using AI and satellite-based Earth observations, researchers found that little to no industrial fishing occurs in fully and highly protected MPAs. The study dispels longstanding beliefs that these areas simply act as “paper parks” – looking good on paper, but in practice doing little to halt ecosystem degradation.

These findings are encouraging given the ongoing momentum to expand and create new MPAs. Plans for a whopping 11 new marine sanctuaries were approved in Australia at the start of the year, followed by Argentina’s creation of a new protected area nearly the size of the US Yosemite National Park. At the UN Ocean Conference in June, Portugal, Colombia and São Tomé and Príncipe, announced 10 new MPAs, while French Polynesia designated the world’s largest protected area. Spain gave the go-ahead for six new MPAs in October and Pakistan designated its third in November.

Some chose to go beyond new designations, strengthening protections in existing MPAs. In the Philippines, a huge coral hotspot off the coast of Panaon Island, home to some of the healthiest and most climate-resilient reefs in the world, received new safeguards. Greece became the first European country to ban bottom trawling in all its protected areas and the UK government unveiled a plan to do the same in 41 MPAs.

Bottom trawling, which involves dragging heavy nets along seabeds, is one of the most destructive fishing practices and can cause irreversible damage to marine habitats.

Safeguarding Terrestrial Ecosystems

On terra firma, governments also stepped up to expand protections. While 17.6% of land is protected globally, announcements made this year suggest that momentum is building towards the 30 by 30 target.

In March, Colombia designated a first-of-its-kind territory to protect an uncontacted Indigenous group. Spanning over 1 million hectares, the new area prohibits all economic development and forced human contact, protecting both the Yuri-Passé people and the rich biodiversity who call it their home. Species found in this region include the oncilla – a small spotted cat currently threatened by deforestation, the giant armadillo, and the giant anteater.

In another groundbreaking win, Colombia became the first country in the Amazon basin to declare the entirety of its Amazonian biome as a reserve for natural resources. All new oil or large-scale mining projects will be banned in the reserve, which covers 43% of the country. In a statement at COP30, Irene Vélez Torres, the Acting Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development, said: “We are doing this not only as an act of environmental sovereignty, but also as a fraternal call to the other countries that share the Amazon biome, because the Amazon knows no borders and its preservation requires us to work together.”

In May, the Kyrgyz Republic announced a new ecological corridor linking existing protected areas to form a connected landscape spanning a total of 1.2 million hectares. Growing data shows that maintaining ecological connectivity through these types of corridors is critical for land conservation to be effective. Not only does this ensure that animals can roam freely, but it also helps maintain genetic diversity and nutritional variety.

In Australia, plans were unveiled for the Great Koala National Park – the world’s first protected area dedicated to the endangered marsupial. The proposal will add 176,000 hectares of publicly owned forests to existing protected areas to form a large reserve of prime koala habitat.

Perhaps the most ambitious 30 by 30 commitment of all came from Suriname, which vowed to protect 90% of its tropical forests. With the highest share of forest cover in the world, Suriname is one of three countries that acts as a carbon sink, alongside Bhutan and Panama.

Advancing Environmental Policy

Not all policy progress came in the form of new protected areas. While some countries scaled back or pulled out of their commitments to conserve biodiversity this year, others introduced innovative policies rooted in environmental justice and the recognition of Indigenous rights.

In New Zealand, a significant legal decision granted a mountain area legal personhood, i.e. the same rights, duties and protections as individuals. The mountain and its surrounding peaks are the third natural landmark in the country to receive this status, following the Te Urewera rainforest in 2014 and the Whanganui river in 2017. Previously known as “Mount Egmont”, the legislation also reverts the mountain’s name back to its original Māori denomination: Taranaki Maunga.

More on the topic: Should Nature Have Rights? A Critical Analysis of Ecocentrism and the Future of Water Protection

A similar move is being considered by other countries. In the UK, for example, campaigners have launched a bill to grant legal rights to nature as a whole. If enacted, the legislation would establish a legal duty of care towards nature, and implement a governance structure to monitor and enforce sustainable and regenerative practices. France’s capital Paris, meanwhile, has called on the national parliament to grant legal personhood to the Seine to better protect it from pollution.

In California, the largest-ever “land back” deal in the state’s history returned over 19,000 hectares of land to the Yurok tribe. The area will now form the Blue Creek Salmon Sanctuary and Yurok Tribal Community Forest, protecting one of the most important Chinook salmon runs on the US’ West Coast. The deal is part of the largest dam removal project in the world. Dams built on the Klamath River in the 20th century resulted in the collapse of its thriving ecosystem, with devastating consequences for the Karuk, Yurok, Shasta, Klamath and Modoc tribes. As part of the project, four dams were removed last year, allowing the river to flow freely for the first time in over a century.

Finally, while many felt disappointed by the outcomes of COP30, it did deliver some notable commitments. Governments pledged to recognize, by 2030, the land tenure rights of Indigenous people over 160 million hectares of land – an area the size of Iran. This came alongside a renewed pledge of $1.8 billion to help recognize, manage and protect Indigenous land over the next five years. The Tropical Forest Forever Facility – a financial mechanism designed to permanently fund tropical forest conservation by paying countries for keeping their forests standing – was also launched at COP30.

Upholding Environmental Justice

In many countries, policy changes were achieved thanks to the tireless advocacy and hard work of local communities and civil society. But when political will falls short, environmental advocates are increasingly turning to courts. While legal cases are often drawn out, some notable successes led to transformative rulings for nature and people alike this year.

One case in particular stood out for its global significance. In July, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued a landmark advisory opinion, stating that governments can be held accountable for their greenhouse gas emissions under international law. The case was brought to the world’s top court by a group of law students and activists from low-lying Pacific islands. In a unanimous ruling, the 15 judges concluded that if nations fail to curb emissions, approve new fossil fuel projects, and roll out public money for oil and gas, they could be in breach of international law. Although the ruling is ultimately non-binding, it clears the path for countries to sue each other over climate change. In a huge win for Small Island States, the court also ruled that rising sea levels do not erase borders or maritime jurisdiction.

At a national level, Nepal’s Supreme Court struck down a 2024 law allowing construction in protected areas, deeming it unconstitutional. In a separate ruling, the court also ordered the government to uphold decades-old restrictions on industrial development in the Lumbini area, considered to be the Buddha’s birthplace.

In Indonesia, local communities who spent years petitioning against the development of a controversial zinc-and-lead mine can finally breathe a sigh of relief. The mine’s environmental permit was revoked by the Supreme Court, which found that on-site waste storage was almost certain to fail due to seismic activity, putting nearby villages at risk of over a million tons of mud and toxic waste being unleashed onto them. “This case sets an important legal precedent in terms of environmental protection and the community’s right to a healthy environment,” Rosa Vivien Ratnawati, the Ministry of Environment’s Secretary-General, told reporters.

Onto the Next One

All these quiet victories matter. They remind us that progress comes through sustained action and that even during challenging years, we can forge ahead. Now onto the next one.

Featured image: Serge Melesan.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us