Former US President Franklin D. Roosevelt presided over his country’s economic and social recovery from the Great Depression during the 1930s. FDR’s relief policies, collectively known as the New Deal, increased government spending and regulations, and at least temporarily shifted away from the laissez-faire economic approach that had become scripture in the United States. Among the various initiatives of the New Deal, FDR created the highly successful Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which employed and trained America’s youth in jobs related to conservation. Could it be applied to the modern-day era to both alleviate poverty and conserve the environment?

—

The Civilian Conservation Corps programme came into effect in April 1933, only weeks after FDR had been sworn in as president. It recruited young, unemployed men during the Depression. CCC workers, or ‘enrolees’ as they were known, were provided training to complete conservation projects on federal and state-owned land across the country. These projects included forestry, flood control, wildfire prevention, trail maintenance, erosion control, wildlife management and structural improvements to infrastructure such as dams, bridges and roadways.

The Civilian Conservation Corps programme was specifically open to men aged 18 to 25. Potential enrolees had to meet some requirements, namely being unmarried, 5 to 6.5 feet tall, weigh over 107 lbs and possess at least six teeth.

Enrolees lived in semi-military camps across the country. Food, clothing, shelter and medical care were provided by the government. In addition to job training, enrolees could pursue general education through evening classes. Enrolees worked for a maximum of 18 months, and earned a base monthly salary of USD$30 (the equivalent of around $600 dollars in 2019), of which $25 was to be sent home to families.

By 1933, the unemployment rate in the US had reached an unprecedented 24.9%. Of those unemployed, it is estimated that over a third were under the age of 25. The programme planned to redirect the energy, frustrations and potential of unskilled and undereducated members of what had already been termed a ‘lost generation.’ It was also emblematic of FDR’s life-long interest in nature and environmental conservation. At the time, FDR’s notion of integrating economic stimulus with the preservation of a country’s national resources for the general public’s enjoyment was a novel idea, although the president strongly supported introducing environmental conservation into the national discourse.

The Civilian Conservation Corps was discontinued by the United States Congress in 1942, as the country prepared to enter World War II. By this time, the need for work relief had declined, and the military was specifically seeking out CCC enrolees to aid in the war effort. By this time, the CCC had essentially laid the groundwork for America’s current national park system.

Contemporary sources at the time praised the initiative, and modern retrospections consider the CCC to be among the most popular and successful of FDR’s New Deal policies. Amid current high unemployment among youth worldwide as the COVID-19 pandemic limits economic growth and job opportunities, some have proposed the possibility of resurrecting the CCC. Could a modern incarnation of FDR’s programme alleviate the economic anxieties and environmental impacts of the modern age, and how could it be implemented in developing countries?

Economic, Environmental and Social Dimensions of the Civilian Conservation Corps

By the programme’s termination in 1942, the CCC had employed nearly three million men, around 5% of the male population in the US at the time. It was credited with improving the physical and psychological condition of a beaten down generation. It heightened morale for a disillusioned youth, and increased the employability of young, undereducated workers, who acquired important skills during their time with the CCC.

The voluntary educational initiatives offered by the CCC were extremely popular, as over 90% of enrolees over the programme’s nine-year existence participated in courses such as reading and writing, mathematics, engineering, art, mechanics and first aid.

In 1939, 91% of CCC enrolees that year had participated in at least one of the educational programmes offered at camps. The 1939 class of CCC workers included 8 936 enrolees who learned to read and write, 5 176 who received an eighth grade-level of education, 1 408 who received high school diplomas and 97 who received college degrees. In the same year, over 30 000 enrolees secured jobs that required skills taught at CCC training and educational camps, while countless others continued their education following their CCC commitment.

In addition to its economic and social benefits, the CCC has left behind a strong environmental legacy. The programme is credited with planting three billion trees, half of all the reforestation work ever done in the country, in the span of nine years. It was also responsible for the development of more than 800 new state parks, and optimising approximately 40 million acres of farmland through erosion control work. Structural improvements and maintenance of key infrastructure was also undertaken, as drainage ditches, dams and fire control towers were rehabilitated across the country.

Possibly the most crucial impact of the CCC, however, was that it expanded the capacity for conservation work in the US. Many of the CCC’s former enrolees, especially those who served in the military and were beneficiaries of FDR’s 1944 GI Bill that ensured free tertiary education for war veterans, received university degrees and became leaders in the fields of forestry, wildlife preservation and resource management.

While its legacy is predominantly positive, the CCC was a product of its time and its failures should not be ignored. The CCC was only open to male applicants, and reinforced traditional gender roles by forcing young women to remain at home while men left to becomes enrolees. It also limited opportunities for women to pursue careers in forestry and environmental conservation, and led to the formation of a male-dominated industry over subsequent decades. Eleanor Roosevelt, an important figure in the history of women’s rights and FDR’s wife, was aware of these issues, and created a sister initiative to the CCC known as the She-She-She Camps.

The initiative allowed women to live independently with close support for months at a time and earn an education. The programme differed from its male counterpart in that it did not require manual labor from its enrolees. Instead, the female camps focused on vocational training, counseling and encouragement. The She-She-She Camps prepared women for a variety of careers, not necessarily related to conservation, and received a large volume of applications. However, it was also mocked and criticised extensively by lawmakers, and a lack of government funding meant that only 8 500 women served between 1933 and 1942.

You might also like: South Africa Plans to Reach Net Zero Emissions by 2050, But Can it Let Go of Coal?

Image 1: History.com; Eleanor Roosevelt speaks at a camp in Bear Mountain, New York, August 1933; History.com

The Civilian Conservation Corps was implemented while segregation laws still existed in much of the US, and the enrolees’ camps were no different. Despite African-Americans losing their jobs at a higher rate than other groups, the CCC capped Black enrolment in the programme at 10%, reflecting the racial makeup of the United States at the time. Camps were initially integrated, although the CCC eventually succumbed to political pressure from southern states and began segregating camps based on race. Most camps that housed African-Americans were placed in extremely remote locations. It is estimated that nearly 150 CCC camps exclusively housed Black enrolees, however the first camp to boast an African-American staff and administration was not established until 1940. There were approximately 250 000 African-Americans and 80 000 Native Americans enrolled in the CCC. A strength of the initiative, considering the era, was that there was no disparity in compensation or benefits based on race.

Image 2: The Living New Deal; An instance of a racially integrated camp at Marsh Field in San Diego, California; thelivingnewdeal.org

Sustainable Development as Stimulus for Economic Recovery

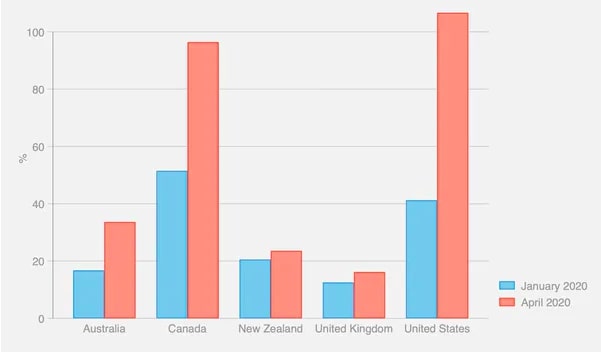

In April 2020, the United States reached an unemployment rate of 14.7%, the highest rate since the Great Depression. Young people are encountering the most difficulties, as it is estimated that over 7.7 million Americans under 30 are currently unemployed. The pandemic has severely affected the service industry, with the hospitality and retail sectors suffering the most. These sectors tend to be the largest employers of young, pre-professional and low-wage workers. These statistics do not include young people who have had to resort to part-time work, were furloughed, or have dropped out of the labour force entirely.

Figure 1: OECD Labour Force Statistics; Unemployment rates by age group in OECD countries from February to July 2020; oecd.org

As governments begin to contemplate policy and stimulus measures to encourage recovery, reconciling economic targets with environmental conservation presents an opportunity. The CCC addressed the broader societal need for environmental resource conservation, while also working to rectify the plight of America’s youth by providing jobs and education. Our contemporary broad societal challenges are climate change and environmental degradation. The most severe repercussions of these crises will fall on the shoulders of the world’s youth, who now also face severe economic struggles in the pandemic-induced recession.

A series of underlying issues exacerbate the current climate crisis. Outdated infrastructure, inefficient energy systems, overused and degrading land and polluted waterways all add to the mounting environmental challenges society faces. To move forward and meet the climate crisis on level terms, the growth of sustainable jobs will play a critical role.

Could a modernised model of the CCC work when facing these challenges? The transparent answer is that there is no reason it shouldn’t. Climate change ranks as the most concerning and important issue for global youth, and an international survey found that 89% of young respondents believe that their generation can and should play a key role in combating climate change. There is an abundance of social and civic will on behalf of young people to donate their time, energy and skills to the fight against climate change.

A modern CCC could adapt some functions of the New Deal programme directly. A 2018 study found that 90% of protected sites worldwide were suffering from degradation caused by human activity. Governments can fund job training for out-of-work youth interested in environmental conservation and set people to work in restoring protected lands. This could include maintaining trails, replanting trees and clearing invasive species.

More than 130 regional conservation corps agencies exist in the US, as holdovers of the CCC model. Through a mix of federal and private funding, some of these organisations have had great successes on a local level. The Mile High Youth Corps in Colorado, for instance, has successfully attracted young volunteers from a range of backgrounds to help combat the devastating wildfires that ravaged the state earlier this year. The California Conservation Corps has also mobilised young workers to participate in the state’s COVID-19 response.

A modernised version of the Civilian Conservation Corps should also transcend the original initiative’s mandate and focus on the climate crisis and transitioning to a green society. Green construction work, such as solar panel installation, weatherising buildings and retrofitting obsolete equipment are important contributions that do not require a high degree of technical skill or expertise. Firms that specialise in green construction already exist in high numbers, and can play an important role in the transition towards a low-carbon society. Government plans can set aside grants and contracts for these companies, with the expectation that these firms will make use of their funding to employ and train young workers.

A modern CCC can also radically augment the capacity for a country’s sustainable development industry, by creating a transparent career pathway for young people to embark upon. Participation in a long-term conservation programme could entail lowered university tuition costs, preferential selection for advanced degrees in sustainable development and guaranteed positions with conservation firms after degree attainment. A modern CCC should incentivise participants to pursue lifetime careers in conservation, by partnering with pre-selected labour collectives, universities and trade schools.

For such an initiative to survive and be a lasting force on job growth, it will be important for governments to clearly define an identity. One of the reasons FDR’s incarnation of the CCC only lasted nine years was because it was never considered to be anything more than an economic relief programme. When vast employment opportunities related to the war effort beckoned, these relief programmes were the first to be scrapped. A modern CCC should emphasise its educational component as what sets it apart from a standard public works or economic relief scheme. A modern CCC should be defined as a stable career pathway system for young men and women, clearly emphasising its educational benefits.

A Global Conservation Corps

In June, the UN’s International Labour Organisation estimated that over $10 trillion had been spent by governments worldwide in unemployment relief measures throughout the pandemic. That number is expected to rise and mainly reflect measures taken by wealthier countries. The report also predicted that falling working hours globally would amount to the equivalent of 340 million full-time job losses compared to 2019, again without proportionally representing unemployment in developing nations, where much of the workforce participates in the informal job sector.

Figure 2: The Conversation; Pre-COVID and current unemployment insurance replacement rate for a single person (% of wages replaced by unemployment benefits); Australian Government, Government of Canada, Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (US) & Department for Work and Pensions (UK).

When evaluating the practicality of an initiative modelled on the CCC that is not restrictive to any one country, the first question surely revolves around funding. How would developing countries be able to afford and implement such a programme?

Here, it is helpful to understand the role transnational institutions play in conservation. The World Bank has historically been the world’s largest funder of conservation projects, offering $5.1 billion in funding between 1991 and 2018 to biodiversity conservation projects worldwide, partly through its Global Environment Facility financing mechanism. This mechanism facilitates cooperation between governments, private sector actors and multilateral institutions to provide funding.

International NGOs also play an important role in conservation projects. Major organisations, such as the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), Conservation International and the Birdlife Fund are all major donors to conservation projects. For decades, international NGOs have perfected the art of transnational networking by mediating between states, market actors and regional NGOs and institutions. International NGOs have accomplished impressive conservation goals across the world in large part due to their connections in politics and industry, access to state and transnational funding and effective networking.

In short, the funding to make variations of a Civilian Conservation Corps globally ubiquitous and adaptable to diverse circumstances already exists. Transnational institutions offer grants and funding worth billions of dollars for developing nations to achieve conservation goals, and wealthier states are spending trillions on unemployment benefits.

If governments can see the value of conservation programmes and network efficiently with international actors, global youth can benefit immeasurably. As developed nations will likely have the funds to implement such initiatives independently, international funding can be directed towards poorer countries, where young people are more likely to lack varied career options or access to higher education.

Making training and educational opportunities accessible to global youth is paramount. This can be accomplished by involving international NGOs. These organisations can either use their expertise to train workers directly, or employ their global network to find and hire appropriate experts and educators.

To recover from the pandemic and the recession, governments will inevitably need to increase spending. Markets will not fix themselves and states will need to intervene. Governments are currently spending obscene amounts to support unemployed people, leading to serious budget deficits worldwide and declining mental health conditions for the unemployed. These funds do not need to be spent on the preservation of unsustainable industries. To complete a transition towards a clean economy and a low-carbon future, governments need to recognise which components of their economy do not work and redirect their workforce, coordinate with international actors and dedicate funds to the development of sustainable jobs and industries.