This is Earth.Org’s comprehensive analysis of climate change vulnerabilities, updated emissions pledges and environmental policies by sector in the European Union.

—

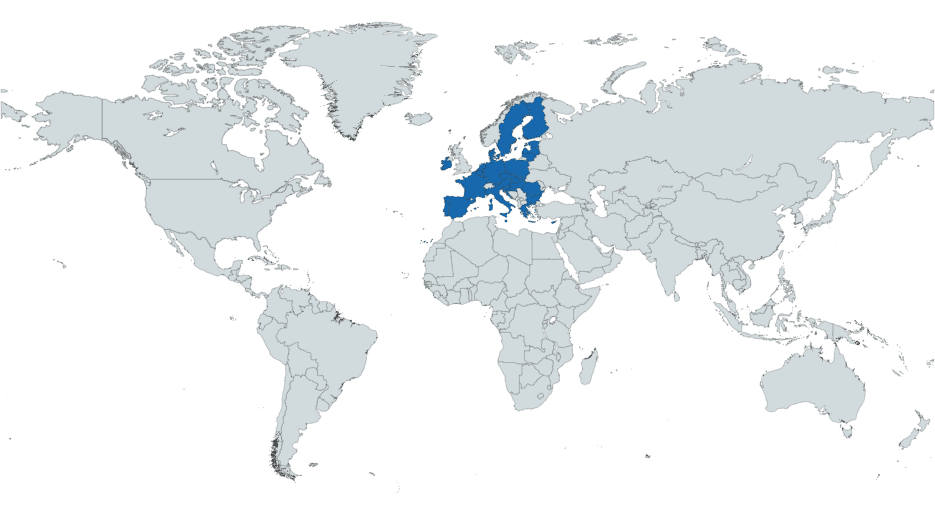

For the purposes of this Country Page, the European Union bloc including all 27 of its members will be considered a single entity and compared to other countries as such. The policies and circumstances of individual countries within the EU bloc are evaluated in more detail within their specific Country Pages.

- Population (2021): 447 512 041 (3rd most populated region).

- GDP per capita (2021): USD$ 38 234 (Ranked 25th globally).

- Emissions (2021): 2.4GT of CO2 emissions (Ranked 3rd highest emitting region).

Pledges & Targets

- Paris Agreement & NDC: The EU’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), last updated in December 2020, targets the following:

-

-

- The EU bloc and its 27 member states are committed to acting jointly and achieve a net domestic reduction of at least 55% in GHG emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

-

- Road to Net-Zero: In March 2020, the European Council endorsed and adopted the objective of achieving a climate-neutral Europe by 2050. As part of this objective, each EU member state is expected to submit their respective, national long-term strategies to reach carbon neutrality by 2050.

- The EU has also announced serious intent to implement a carbon border adjustment tax to target carbon-intensive imports from countries with more lax regulations. The tax is expected to begin operation in 2026, following a transitional period between 2023 and 2025.

- Clean Energy Goals: The EU has announced a target to increase its share of renewable energy in final energy consumption to at least 32% by 2030, almost double 2017 levels.

- Eliminating Emissions: The EU has pledged to cut methane emissions, a highly potent greenhouse gas, by 30% by 2030.

State of Affairs

After updating its NDC in December 2020, the EU is taking on a more ambitious and decisive role in its climate policy. Its original goal, to achieve a 40% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030, was widely seen as insufficient given the wealth and prosperity enjoyed by the EU’s various advanced economies, and the new target is more compatible with what the bloc is capable of achieving. However, to be in line with its 2050 carbon neutrality goal, the EU would need to aim higher, for a reduction target of at least 65% by 2030. While there is yet time for the bloc and its member states to update their commitments further, the EU’s current policies are not compatible with the overall carbon neutrality goal.

The EU considers climate action to be a fundamental pillar of its post-COVID-19 economic recovery plan, which is expected to direct large sums towards moving away from fossil fuels, expanding the capacity of renewable energy in the bloc and electrifying several economic sectors, mainly pertaining to transportation. The EU is poised to implement the world’s first carbon border adjustment mechanism, which will restrict imports from countries still dependent on fossil fuels in their manufacturing industries. The EU carbon emissions trading system has also shown signs of effectiveness in reducing the bloc’s emission rates, although has encountered several implementation struggles.

Given its wealth and capacity for innovation, many consider the EU as the only credible candidate to counter the US and China’s claim for the title of global climate leadership. To do so, the EU would need to ramp up its ambition considerably, but its new NDC and post-COVID-19 economic recovery plans are positive signs. The EU is ultimately beholden to its member states, however, and while some countries are doing very well in decarbonising their economies, others are reluctant or unable to make the same efforts.

Climate Vulnerability & Readiness

As a geopolitical bloc spread over several countries with varying geography, climate and economic capacity, the European Union has a diverse set of climate vulnerabilities, and different EU countries can have vastly divergent levels of resilience to climate change. Per the European Environment Agency, however, the continent will encounter several shared threats, specifically related to droughts, heatwaves and flooding.

Droughts will primarily affect warmer southern European countries in the Mediterranean basin, specifically affecting Italy, Spain, Greece and Turkey. This region is naturally inclined towards hot, dry summers, and seasons will be even hotter and drier with temperature rise. This could lead to water shortages, crop failure and a higher occurrence of wildfires in mismanaged areas, as well as worsening public health conditions in cities and regions affected by heatwaves. Weather-driven fire danger during summers could increase by over 40% in southern and western Europe, with northern countries also experiencing significant increases.

As southern regions warm, countries located in central and eastern Europe will become a lot wetter. Places such as Ukraine, Poland, Romania and European Russia will experience increases in rainfall by over 35%. During winter months, southern Europe could also experience a frequency up to 25% higher than today of heavy and sudden rain occurrence. This increase of rainfall, especially during winter months, could lead to flash flooding and damage essential infrastructure.

Sea level-rise will affect every coastal region in Europe, impacting coastal ecosystems, settlements and human lives. Receding coastlines and periodic flooding will be particularly severe for countries and regions with low-lying terrain. In northern Europe, this will affect the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, northern Germany and southern Sweden. In the south, sea level-rise poses the highest risk to the southern coast of France and the northeastern Italian coastline facing the Adriatic. The threat level to human lives and potential economic losses varies depending on the emissions scenario and degree of sea level-rise, but under a high emissions scenario, where the world is unable to keep temperature rise below 2C above pre-industrial levels and insufficient investments are directed towards strengthening infrastructure, anywhere between 1.5 and 3.6 million lives would be at risk, and the economic cost could rise to as high as €31 billion by 2100.

Despite the severity of hotter temperatures, flooding and sea level-rise in the EU, the high economic capacity of the bloc means that most of its member states will be able to weather the worst impacts of climate change. Many countries will be able to see and anticipate the biggest threats, and prepare accordingly by investing in protective measures and resilient infrastructure. Poorer and less stable nations in eastern Europe may encounter more difficulties in directing sufficient funds towards these initiatives, but it appears that the wealthier western half of Europe will be grappling with the worst impacts.

While Europe may be able to weather the proverbial storm in a lower emissions scenario, a consensus is emerging that the bloc’s biggest vulnerability lies in its dependence on global systems and supply chains remaining intact, meaning that the worst impacts of climate change for the EU may be the ones that occur well beyond its borders. Disruptions to global trade, the potential spread of virulent diseases, geopolitical and security risks and climate change-induced migration will mainly occur in and from the Global South, but will place a heavy strain on the resources of wealthier, more resilient nations such as those in the EU.

Environmental Policies by Sector

Energy

- Per Eurostat, renewables made up the largest share of primary energy production in the EU in 2019, with a share of 36.5%.

- Renewables were followed by nuclear at 32%. Fossil fuels accounted for 28.4% of total energy production in 2019

- The energy mix shares of nuclear and fossil fuels have decreased dramatically since 1990, especially natural gas which has been cut by nearly half. Renewables in the meantime have grown by 48.3% in the same time period.

There is substantial variation between member states in how much energy is sourced from renewable sources. Sweden, for instance, receives more than half of its energy from renewables in 2019, while other countries such as Malta, the Netherlands and Belgium receive less than 10% from renewables. Some countries, such as Germany, have opted to actively denuclearise their energy grids, which has led to a slight uptick in fossil fuel use, while others, such as France, remain reliant on nuclear, keeping fossil fuel’s share down but making the country somewhat laggard in implementing renewable energy.

While the EU has set out general targets for net-zero energy grids, individual member states are at different stages of decarbonisation, with some sorely lacking in sufficiently ambitious policy. These nations will have to adopt stronger environmental and decarbonisation goals and policies to meet the EU’s general targets.

Transportation

- Per Eurostat, transportation was the EU’s most energy-intensive sector by final energy consumption in 2019, accounting for 30.9 of total energy consumption.

- International aviation makes up by far most of the EU’s energy use for transportation, followed by road travel and domestic aviation. Rail travel is the least energy-intensive mode of transport in the EU.

- The EU’s transportation sector remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels, and per the European Environment Agency, accounts for one quarter of the bloc’s greenhouse gas emissions.

- Per the European Commission, transport in the EU still relies on oil for 94% of its energy needs.

- Per the International Council on Clean Transportation, the electric vehicle share of the EU’s total vehicular fleet stood at 11% in 2020, up from 3.6% in 2019.

Similarly to the EU’s energy statistics, there is significant variation between member states as to what extent individual transport sectors have been electrified. Norway’s share of newly registered electric vehicles stands at a staggering 75% of total cars sold, while the shares of 2020 registered electric vehicles in Spain and Italy are less than 5%. The overall outlook for electric vehicles in the EU trends strongly positive, as major market growth has been made in virtually every member state over the past year. However, costs remain high, and not every country has implemented sufficient subsidisation programs.

In terms of wider electrification of the EU’s transport grid, fossil fuels will presumably remain a part of the picture for the foreseeable future, as aviation remains the most carbon-intensive transportation method on the continent. Some countries have implemented policies to reduce air travel over short distances, such as France’s move to ban short-haul domestic flights where rail alternatives exist, but despite these piecemeal measures, the bloc as a whole has not implemented any notable policies to divert traveller traffic away from planes and into more easily electrified trains and mass transit systems.

Biodiversity

- Per the European Environment Agency, 26% of the EU’s land is protected, while around 12% of the EU’s seas are considered Marine Protected Areas.

- Per the World Bank, 75% of the EU’s population is urbanised.

- Per the World Economic Forum, forests covered 42% of Europe’s land in 2019. Between 1990 and 2015, the total land area covered by forests on the continent increased by around 90 000 hectares, approximately the size of Portugal.

While deforestation trends have swept most countries across the globe, the EU has largely bucked the trend and been able to maintain large swathes of forest. Sweden, Finland, Spain and France lead the way in terms of forest cover, with Sweden and Finland both setting aside approximately 70% of their land to forest cover. However, it is important to note that the majority of the EU’s large forest cover is not natural forest, as most have been planted and are used to produce wood to make paper, or timber for construction, or as fuel. These forests are routinely felled to then be replanted in larger numbers. Overall, the amount of forest cover is increasing, as more trees are being replanted than felled, and these trees do act as effective carbon sinks and homes to local fauna, but they are not a perfect substitute for natural trees in protecting biodiversity.

The EU’s protected marine areas are referred to as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). While MPAs cover a wide expanse of waters, they have frequently come under fire for lax management and control, with one study finding that up to 96% of marine parks allowed illicit destructive activities to occur within their boundaries. These activities include illegal fishing, bottom trawling, seabed mining and destructive industrial or infrastructural development. Over half of MPAs reported no management at all. Over the past decade, MPAs were established at a notably fast pace, and criticism has been levied at a perceived sacrificing of quality for the sake of quantity.

Wildlife

- Per the European Parliament, the EU possesses 1 677 species at risk of extinction, out of 15 060 species assessed by the UN. Over half of Europe’s endemic trees are at risk of extinction.

- Since 2015, 36 species have become extinct in Europe.

- The EU has established legislative provisions that recognise animals as sentient beings and protect their rights as such.

Per the French multidisciplinary organisation, Fondation de Droit Animal, The EU adopted laws that prohibited the inhumane slaughter of animals in 1974, and has since expanded its legislation to cover more areas of animal welfare. Landmark pieces of legislation included a 1998 directive that decreed the humane treatment of all animals kept for farming purposes, and the 2009 Lisbon Treaty that officialised the EU’s recognition of animals as sentient beings. EU legislation on animal welfare primarily refers to the humane treatment of farm animals, although the bloc has also implemented provisions protecting animals used for scientific purposes and those kept in zoos.

As one of the world’s major exporters of food and animal products, there is however some institutional resistance to protecting animal rights, particularly where enforcement is involved. While the EU as a whole provides a robust series of frameworks, training programs, scientific expertise and consulting services to help safeguard animal welfare, the responsibility of enforcement primarily falls on the shoulders of the member states, which can occasionally be lacking, since enforcement can still oftentimes be seen as an economic hurdle rather than an opportunity for more efficient production.

Pollution

- Per Eurostat, the annual mean concentration of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in urban areas of the EU bloc was 12.6 μg/m³ in 2019, following several years of progressive decline since a high of over 19 μg/m³ in 2011.

- The bloc has set an annual limit value for PM2.5 of 25 μg/m³. Anywhere that registers levels above this limit is considered very poor air quality.

- Per the European Environment Agency, 19 major cities in the EU possess poor or very poor air quality levels. Data is collected only in cities with adequate air quality monitoring capabilities.

The EU possesses a robust network of air quality and pollution management standards, which have made its larger cities substantially more livable than comparable metropolises across the globe. Since the 1970s, the EU has provided guiding frameworks for member states and cities to follow, mainly directed at controlling emissions of harmful pollutants into the atmosphere, improving fuel quality, and integrating environmental protection requirements into the transport and energy sectors. Important legislation includes the 2013 Clean Air Package, which set out objectives for 2020 and 2030 to reduce emissions of major pollutants, including sulphur dioxide, lead, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and benzene.

As always in the EU, success has been distributed unevenly. Cities with the highest air quality tend to overwhelmingly be in northern Europe, mainly Scandinavian and Baltic countries. Western and central European countries, such as France and Germany, perform reasonably well, with a few statistical outliers. However, southern and eastern European countries, including Italy, Poland and Bulgaria, tend to have the worst air quality standards recorded, in part due to climate, but also due to lack of investment and governmental attention towards reducing pollutants and waste.