The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997 and came into force in 2005. It aims to reduce greenhouse gases emissions by setting individual targets with parties to the Protocol.

Earth.Org seeks to assess the Protocol’s effectiveness, and identify what we can learn from its execution.

—

Large Emitters Lack of Commitment

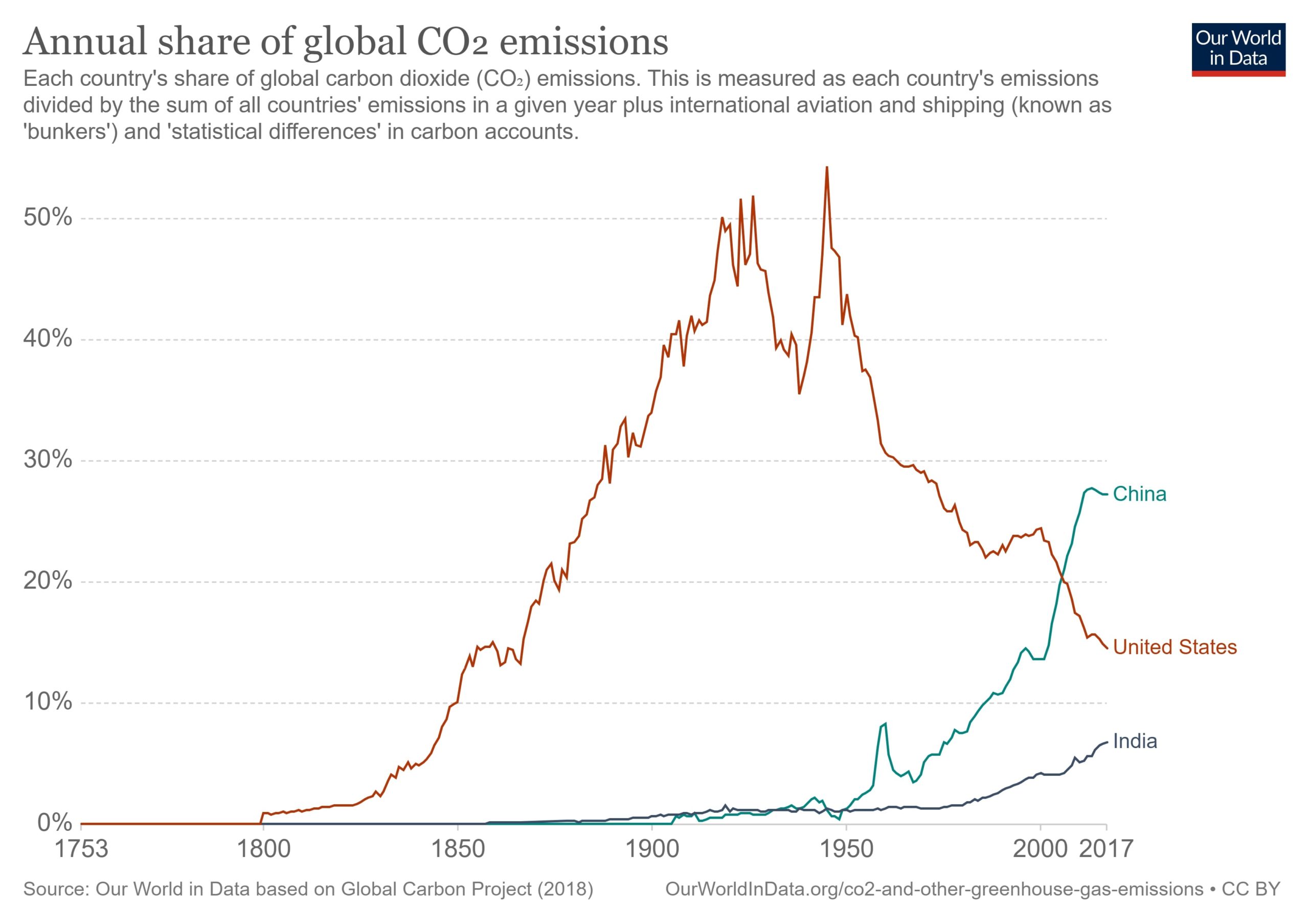

The Kyoto Protocol binds 37 industrialised nations to reduce emissions, however, developing countries are only asked to voluntarily comply since their contributions would be more symbolic than anything else. China and India, both still developing and housing the 1st and 2nd largest populations on earth, knew fully well their emissions were going to keep rising as a consequence of their growth. Thus, they chose not to adhere to the Protocol, immediately limiting its potential as their emissions alone would outweigh the reductions of other smaller nations.

Source: ourworldindata.org

The U.S. was originally part of the agreement, but dropped out in 2001 due to the concern of an economic turndown. Mr. George Bush, the former US president, stated that complying with the Protocol would mean limiting the country’s growth and argued that there could be other ways to cut emissions without harming the economy.

When Canada withdrew in 2011, many thought the Protocol had failed. A year later, estimates showed a 20% drop in developed countries emissions (vis-a-vis 1990 levels). Despite global emissions rising by an overall 38% over the same period, Kyoto Protocol’s effect remains significant.

Emissions trading

Per the Protocol’s requirements, developed countries were to cut greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 18% by 2013-2020 compared with 1990 levels. Joint implementation, defined by Article 17 of the Protocol, allowed developed countries who are unable to meet their targets to purchase emission credits from developing countries. This effectively allowed developed countries to buy their way around their commitments.

The initial idea was to direct finance toward the most cost-effective projects, while maintaining climate benefits. A 2015 report revealed that around 80% of the projects under the Kyoto Protocol’s emissions trading system were of low environmental quality. The joint implementation system actually increased emissions by roughly 600 million metric tons. Russian and Ukrainian companies were the main profiteers, having issued 90% of the credits.

A Limited Success

The Kyoto Protocol’s deadline is 2020, so by definition it is not meant to be a long-term solution. As we saw earlier, developed countries reduced their emissions by 20% overall thanks to this agreement, which is both commendable, but insufficient.

How then to assess its effectiveness? Had it been a resounding success, fully achieving its potential, it would have curbed the US, China’s and India’s emissions by 20%, along with other committed nations. Were this the case, we would still require more ambitious goals like those of the Paris Agreement in order to stay below 1.5 or 2C warming. Further, it only applied to industrialised countries, meaning it could not limit the growth of those in development which together, account for 75% of global emissions.

It is more reasonable to see the Kyoto Protocol as a first step toward a greater international commitment to reversing greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. Along the way, we have witnessed how some loopholes can be exploited to skirt pledges, and hopefully we have learned from these mistakes.

This article was written by Jennie Wong.

You might also like: What is the Kyoto Protocol?

References

-

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, What is the Kyoto Protocol?, from: https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol

-

BBC News, Kyoto: Why did the US pull out?, from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/1248757.stm

-

Our World in Data, United States: CO2 Country Profile, from: https://ourworldindata.org/co2/country/united-states?country=~USA

-

Deutsche Welle, Tackling climate change from Kyoto to Paris and beyond, from: https://www.dw.com/en/kyoto-protocol-climate-treaty/a-52375473

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)