New forest carbon flux maps published last month present a paradigm shift for monitoring forests worldwide. The maps integrate data from various sources to show carbon emissions and sinks at unprecedented detail, offering long-awaited guidance to present and future climate policy and conservation efforts.

—

The study, published in Nature Climate Change, also shows that tropical rainforests are by far the most important ecosystems in the fight against climate change.

A new framework

Current forest conservation efforts operate largely on a regional basis. Studies and reviews from different states and organizations report forest carbon emissions according to their different methods, relevant to their objectives, capabilities and geographic scales. This makes it difficult to compare and consolidate datasets, and so the big picture of global forest carbon dynamics has been an elusive yet imperative intent.

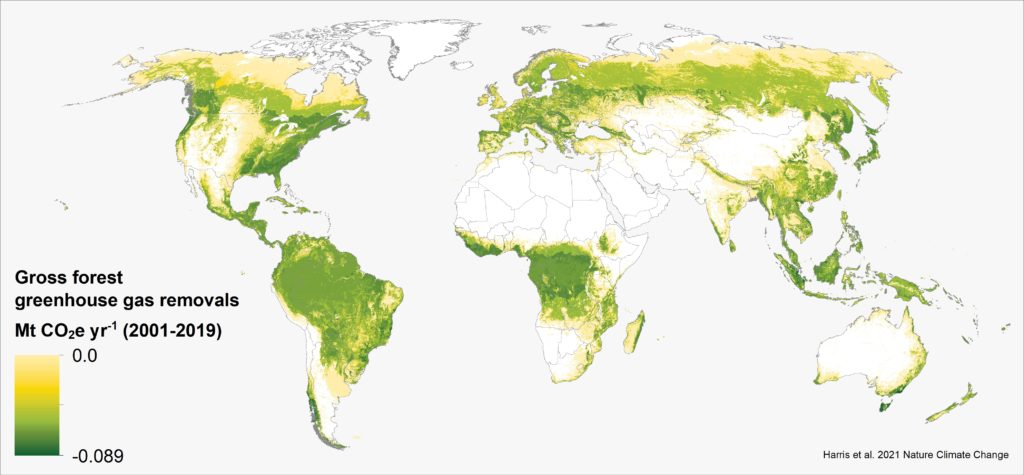

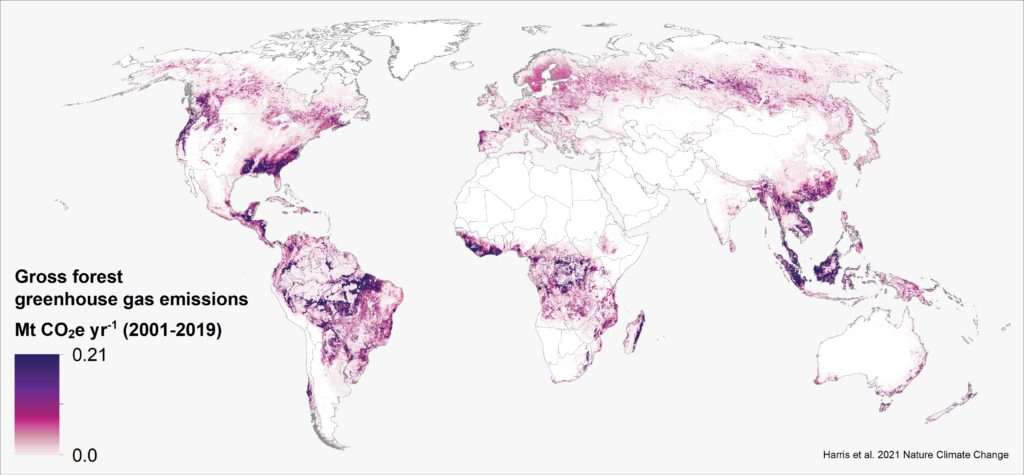

The novel, consistent global analysis platform here presented is thus a game-changer. It consolidates measurements from satellites and atmospheric and ground-level instruments across the world to present global maps at an extraordinary 30m/pixel resolution. Forest carbon sources and sinks can be easily identified down to the community scale.

“Our global maps are like getting new prescription glasses and finally being able to see the movie screen,” says David Gibbs, study co-author and GIS Research Associate at World Resources Institute.

As new data is generated, the framework can be updated and even more complete maps made. By narrowing down what is known about forest carbon, researchers can identify what is not known, and thereby better quantify uncertainties and better allocate future resources.

A more robust understanding of forest carbon fluxes also means better understanding the overall global carbon cycle, key for accurately predicting how much and how fast the planet has yet to warm. The IPCC’s 5th Assessment Report indicated that land use change such as deforestation accounts for about 12 percent of global GHG emissions each year, and another 12 percent comes from agriculture, the main driver behind deforestation.

What the maps show

The good news is that over the last decade forests were an overall net carbon sink, each year absorbing about 1.5 times the annual carbon emissions of the United States.

“Of course, forests could be an even larger carbon sink and doing even more to mitigate climate change if we destroyed fewer of them,” said Gibbs.

The study confirmed that tropical forests are the largest contributing forest type to global carbon fluxes.

Among the world’s three largest rainforests, only that of the Congo River Basin is still a strong net carbon sink. The rainforest in Southeast Asia, much of it in Indonesia, been largely cleared for plantations, had its peat soils drained, or been damaged by fires; it’s now a net source of emissions.

The Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, is on the cusp of becoming a net source if deforestation continues as it has, especially in the last four years. The primary driver there is forest clearing for soy monoculture farms and livestock grazing. Commercial farms created just in recent years span thousands of hectares and export millions of tons of beef and grains each year.

It is now evident that cutting down such old-growth, primary forests as that of the Amazon is the worst thing happening right now in regards to forest carbon. Established forests, rather than any new wooded areas, are predominantly responsible for carbon capture; their stores have taken hundreds of years to accumulate, and once released that carbon will be out in the atmosphere, warming the planet, for generations to come.

Planting new trees can offer a hopeful sight, and there are ways to do this well, but over the last two decades these accounted for only 5% of the global forest carbon sink.

The best thing we can do is thus to protect the mature forests we still have.

What can be done

The world loses a staggering 27 football fields of forest every minute.

That’s according to the latest report by the New York Declaration on Forests (NYDF), a major international declaration to protect forests whose ambitious goal is to halt all natural forest loss by 2030.

The NYDF’s latest focus report found a significant gap between commitments and actions against deforestation. For instance, in 2019, one-third of 350 major companies whose supply chains contribute to deforestation reported nothing about mitigating the practice. Closing this gap will require effective legislation, enforcement and management. A game changer would be companies engaging in jurisdiction that reduces deforestation, lending their finances, their expertise, and their voice.

National parks and protected reserves, such as indigenous territories in the Amazon off-limits to mining and clearing for farms, are an equally powerful tool – nearly a third of the world’s forest carbon sinks are in areas such as these.

Understanding and responding to climate change requires gathering the myriad tidbits of information available and piecing them together to paint a full picture of the situation. Scientists and journalists have been hard at work for over 30 years to do so, and are managing to produce unequivocal results today, greatly thanks to satellite technology. The maps above are a powerful argument for action, and tool for decision-making.

This article was written by Debbie Sanchez.

You might also like: The State of the Climate #2

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)