Gaining an extra few pounds is no longer a personal issue, but a representation of failure of the systems and environment we live in today. Obesity and climate change are considered two of the greatest threats to our planet and its inhabitants. A recent report by The Lancet Commission on Obesity (or The Lancet in short) has illustrated how closely interconnected these two health pandemics are.

—

Malnutrition, especially obesity, is the leading cause of poor health worldwide. Despite no obvious connection, climate change is also a contributing factor to this issue. And because of its sweeping effects on human health and the natural systems, climate change is now considered as a pandemic by scientists. In this article, we will explain the interactions between obesity and climate change, as described by the study.

The Lancet is a historical and world leading medical journal, ranking second in the general medicine category and considered ethical and credible. Their report, named ‘The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition and Climate Change’, outlines the challenges posed by the combination of malnutrition and climate change. It is a follow-up of the two Lancet pieces on obesity, published in 2011 and 2015 respectively, as this health issue is becoming a prevailing risk factor for poor health and mortality worldwide.

The report developed a conceptual model for The Global Syndemic based on the concept of syndemic. The term is originally used to describe the interactions between two or more diseases at the individual level, which co-occur in time and place, and share common underlying drivers.

Here are a few figures to give you the lay of land. Currently, obesity and undernutrition each affect approximately 2 billion people globally, and in 2017, over 150 million children were stunted (underdeveloped). The cost of obesity accounts for almost 3% of the world’s GDP, while unmitigated climate change may exceed 7% of the world’s GDP by 2100.

So, how do the two interact? The interactions between the two pandemics are numerous but less certain. With climate change, increasing ambient temperatures and precipitations could contribute to a higher obesity rate due to reductions in physical activity. And as extreme weather increases, fruit and vegetable products will become more expensive, making it harder to maintain a healthy diet. As an example, climate changes in Tigrai, Ethiopia, increased the average price of tomatoes by 310% between 2009 and 2015. The increased price might exacerbate the dietary shift towards processed food and beverages, which are based on inexpensive commodity ingredients such as sugar and oils; and often include multiple preservatives, colourings and flavourings. Although not all processed foods are unhealthy, a high intake of these food products is linked to poor diet quality, obesity and diet-related non-communicable (NCD) risks.

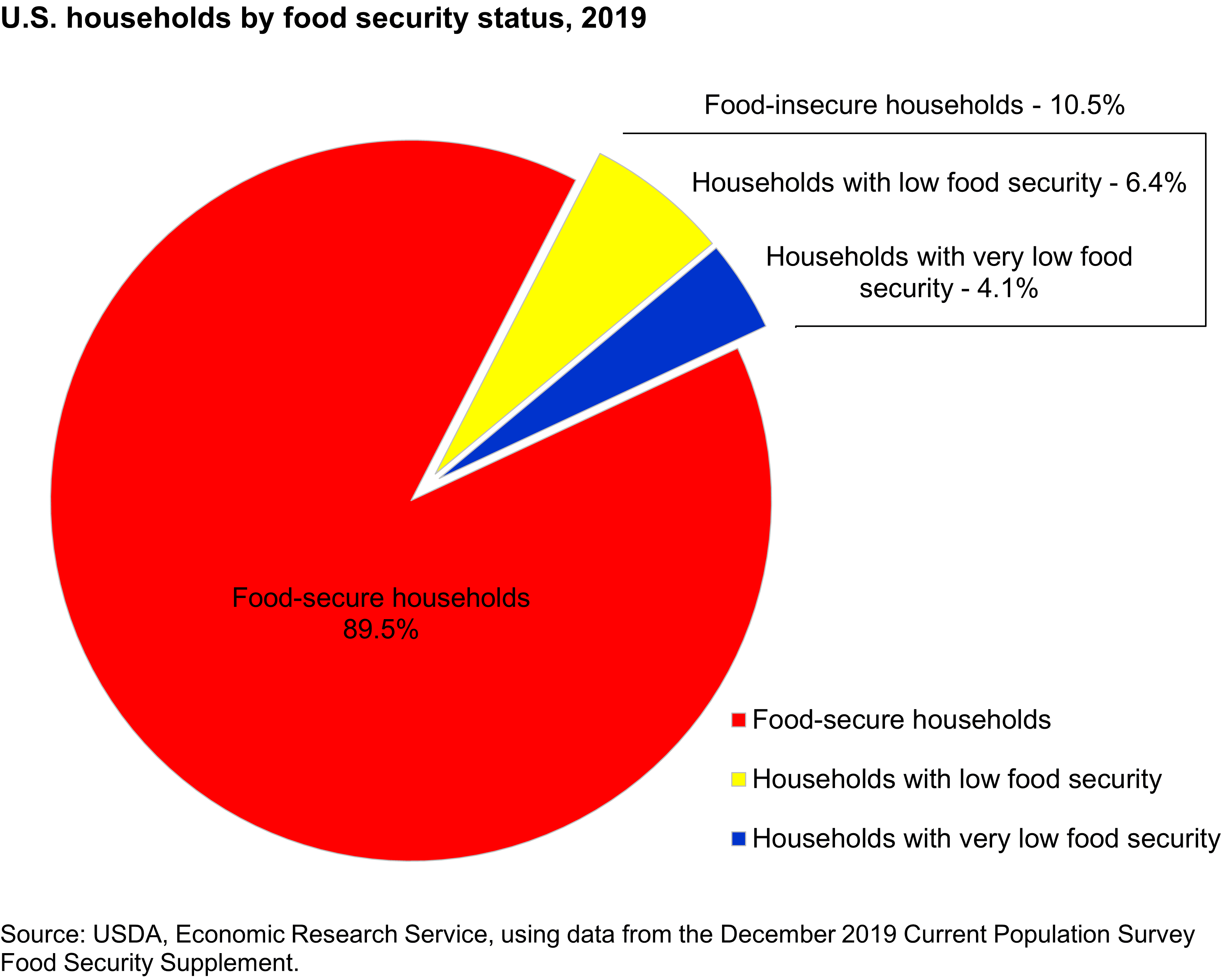

Climate change induced food insecurity is also linked to a higher rate of obesity. Not only in developing countries, food insecurity also happens in economically stable countries such as the US.

According to a study conducted in the US in 2015, food insecure adults had 32% higher chance of being obese. This is a result of those individuals having low nutrient intake, hypertension, diabetes, depression, and other mental health problems.

The major correlation between overeating and climate change is the excess greenhouse gas emissions (GHGEs) that come with an obesity-inducing/maintaining diet. According to the report, obesity is associated with ~20% more GHGEs than the average person’s footprint, of which 52% comes from food and drink consumption.

Research has shown that diets of obese individuals usually have 30% more calories as they require more energy to maintain their greater body weight, and Pradhan’s study (2013) demonstrated the correlation between high calorie consumption and a heavier carbon footprint. In 2015, excess body weight was estimated to affect 2 billion people worldwide; the same year we found that every dietary calorie (1 kcal or 4.184 kJ) on our dinner table is equivalent to 2.21 g of GHGEs. The total impact of obesity on climate change may be an extra 700 megatons per year of CO2eq emissions.

The food system is driving unprecedented environmental damage, accounting for 29% of anthropogenic GHGEs and causing rapid deforestation, soil degradation and massive biodiversity loss. Meat production is at the center of these costs, which extend to human health since a 2016 study demonstrated that high meat availability is the best predictor of obesity prevalence.

Red meat is a well known source for GHGEs, particularly methane and nitrous oxide from enteric fermentation, manure and fertilisation. The production and consumption of red meat have been said to be a substantial driver. Global meat production has increased from 71 million tonnes annually in 1961 to 318 million tonnes in 2014, and is projected to increase further to 455 million tonnes by 2050. The problem may be that consumption per capita has also increased from 20kg to 43kg per person per year from 1961 to 2014. Bearing in mind livestock uses approximately 70% of global agricultural land and is a prime driver of deforestation, matching increasing demand with increased production could have terrible consequences.

The link between malnutrition and climate change seems to be one of two parallel effects, driven by a central causative mechanism: human society. Today, most businesses are driven by profit, and in some cases, so is legislation. The fatal flaw in our system is that the well-being of both our environment and ourselves has not been given a monetary value, meaning it can be carelessly squandered with no immediate (financial) downside. By design, ultra-processed food are highly palatable, cheap, ubiquitous, and contain preservatives that offer a long shelf life. They generate enough profit to warrant aggressive marketing strategies, further increasing their consumption. The industry can even influence policy and acquire subsidies despite the proven detrimental effects of their products. In the U.S., subsidized food is so unhealthy that people who eat the most have a 37% higher chance of being obese.

This article was written by Wing Ki Leung.

You might also like: The Climate Crisis is Threatening Global Food Security.

References

-

Implications of the Western Diet for Agricultural Production, Health and Climate Change: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2018.00088/full

-

Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods: https://www.pnas.org/content/116/46/23357

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)