As human-caused climate change becomes an increasingly tangible part of our lives, its deniers are quieting down. The same political groups, mostly right-wing, who historically discredited the veracity of climate science, are now faced with overwhelming evidence that climate change is real and serious. But these groups are still here, as are their ideologies; they have simply adjusted their messaging. Climate denialism may be on its way out, but in its place environmental concerns are being co-opted in subtler and even more insidious ways, shedding light on a resurgent dark legacy of environmentalism that must be confronted, called ecofascism. How do we tackle it?

—

In terms of its political and economic implications, the challenge of climate change is incompatible with the precepts of traditionally right-wing political groups, who are traditionally married to the ideologies of expanded individual liberties, free markets and small government. Climate change inevitably requires governments to spend and regulate more, and for political parties more dogmatically opposed to such action, like the Republican Party in the US, denying that climate change is a problem worth intervening has been a convenient and attractive weapon of choice.

Today, the irrefutable evidence of climate change has made climate denialism redundant in most of the world. Since ‘once-in-a-century storms’ became an annual occurrence, climate deniers have had very little to stand on, and most major political parties in the world have abandoned denial rhetoric.

But the political precepts of these groups have not changed, and as climate change becomes a larger part of our lives, far-right politicians and groups have started to appropriate environmental narratives to further their goals in other areas. There is growing interest among political scientists in the emergence of what is being termed ecofascism, an ideology that marries environmentalism with more extreme right-wing social and political trends.

Ecofascism is not a new phenomenon, but as lawmakers from across the political spectrum begin to internalise the reality of climate change, environmental policy considerations will take on much more prominent roles in legislation. There is a real threat that far-right political parties and extremist groups and individuals could weaponise climate change and environmental concerns to fuel and justify their own social and political vision of the world. This could be in the form of bolder anti-immigration laws, more stringent population control measures or even outright violence and oppression.

Twisting environmental narratives to validate far-right ideologies and violence sounds dystopian, but it is already happening. Often, these beliefs are based on inaccurate or nonexistent science, and only serve to justify the grievances of unscrupulous leaders or unstable individuals. As climate change begins to take hold of our lives in more and more complicated ways, a new type of environmentalism could emerge, one that is marked by hatred and distrust of outsiders, tribalism and violence. This brand of environmentalism is dangerous, and it needs to be stamped out early by politicians and public institutions.

Ecofascism: The Far-Right & The Environment

In April 2021, the Attorney General of the US state of Arizona sued the Biden administration for failing in its duty to protect the environment. The lawsuit was based on one grievance in particular that the Attorney General’s office had with federal policy: immigration laws.

Biden has made efforts to overturn his predecessor Donald Trump’s immigration policies, including suspending a controversial ruling that forced asylum seekers to wait in Mexico for their US immigration hearings. These policies have increased the number of migrants being legally allowed into the US through the southern border, creating some concern amongst Republican politicians traditionally opposed to expanding legal immigration.

As part of his office’s lawsuit, Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich insisted that Biden’s new policies neglected an environmental review on how more immigration could increase pollution and emissions, saying: “Migrants need housing, infrastructure, hospitals and schools. They drive cars, purchase goods and use public parks and other facilities. Their actions also directly result in the release of pollutants, carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which directly affects air quality.”

Brnovich, who has in the past publicly misrepresented established climate science, is tapping into a common grievance that populist and right-wing leaders commonly rely on: anti-immigration sentiments among the public. By expressing worries over pollution and overpopulation however, the lawsuit essentially weaponises environmental narratives as tools for political gain.

Environmental concerns have been appropriated by far-right political groups for a long time. The Nazi party infamously considered conservation a policy priority, and was among the first political parties in history to champion renewable energy. But assuming that the environmentalism Hitler and his political adherents advocated for came from a place of genuine concern for the Earth and its inhabitants would be innacurate. Nazi environmentalism justified the part’s concerns towards the dangers of overpopulation and resource depletion, itself a driving factor behind the racially-motivated Holocaust campaign.

The Nazi party used environmentalism as a propaganda tool to recruit more members and improve their public standing, but quickly abandoned any ambition concerning environmental legislation as soon as the war started. Since the days of Nazi Germany, this faux environmentalism has been continuously recycled by far-right and extremist groups as a justification for unjustifiable beliefs.

Today, far-right neo-Nazi groups and radicalised individuals have cloaked themselves in environmental and ecological rhetoric to validate their stances, but their positions are largely the same, citing concerns over overpopulation, immigration and multiculturalism as certifiable reasons behind their supremacist views.

In the manifesto of a white supremacist who fatally shot 51 people in a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2019, the killer identified himself as an ecofascist and an ethnic nationalist in the same breath, equating immigration to ‘environmental warfare.’ That same year, another lone gunman shot and killed 23 people in a Walmart store in El Paso, Texas. The gunman claimed to have been inspired by the Christchurch shooter, and he had posted his own manifesto before the attack. The manifesto (named ‘An Inconvenient Truth’ after Al Gore’s environmental documentary) decried unabated population growth, resource depletion and environmental degradation, stating that he was attempting to stop a ‘Hispanic invasion of Texas.’

Disturbed individuals initiating mass shootings while justifying their beliefs with environmental concerns is a very different scenario to someone in Arizona holding reservations about expanded immigration. How did we get here? How large is this dark side of the environmentalist movement? And most importantly, what do we do about it?

A Malthusian Trap?

Right-wing political concerns over immigration and further straining of resources are rooted in the more apolitical fear of overpopulation. These concerns have been around since 18th century British scholar and economist Thomas Malthus proposed his Malthusian mathematical theory of population growth. In Malthus’ view, populations grow exponentially, while sustenance, including food and other basic resources, grow linearly. This would mean that, in the absence of a cataclysmic event that forcefully stops population growth or more draconian population control policy, overpopulation will eventually outpace the availability of basic resources needed to survive.

Malthus’ predictions have been proven wrong several times, and his views have been criticised from across the political spectrum as overly pessimistic and even inhumane. Malthusianism becomes dangerous when its questionable science is taken seriously by lawmakers. In the mid-19th century, the British government scrapped many welfare programmes designed to provide food to the poor, basing this decision on a Malthusian argument that helping the poor only leads to these groups having more children and thereby increasing poverty.

Human populations have almost never behaved in the way theorised by Malthus. As a country’s wealth increases and total fertility rates decrease, societies have an overwhelming tendency to reach a new replacement level; it might take some time for fertility rates to readjust, but they are regardless overwhelmingly inclined to do so. Wee see this in the world today, where the wealthiest nations with easier access to food and resources are having the fewest babies, and poorer countries with higher food insecurity possess the highest fertility rates. For countries that have implemented forceful population control measures, such as the one-child policy in China, the result has been a looming demographic crisis.

You might also like: Opinion: Getting Real About Net Zero by Jonathon Porritt

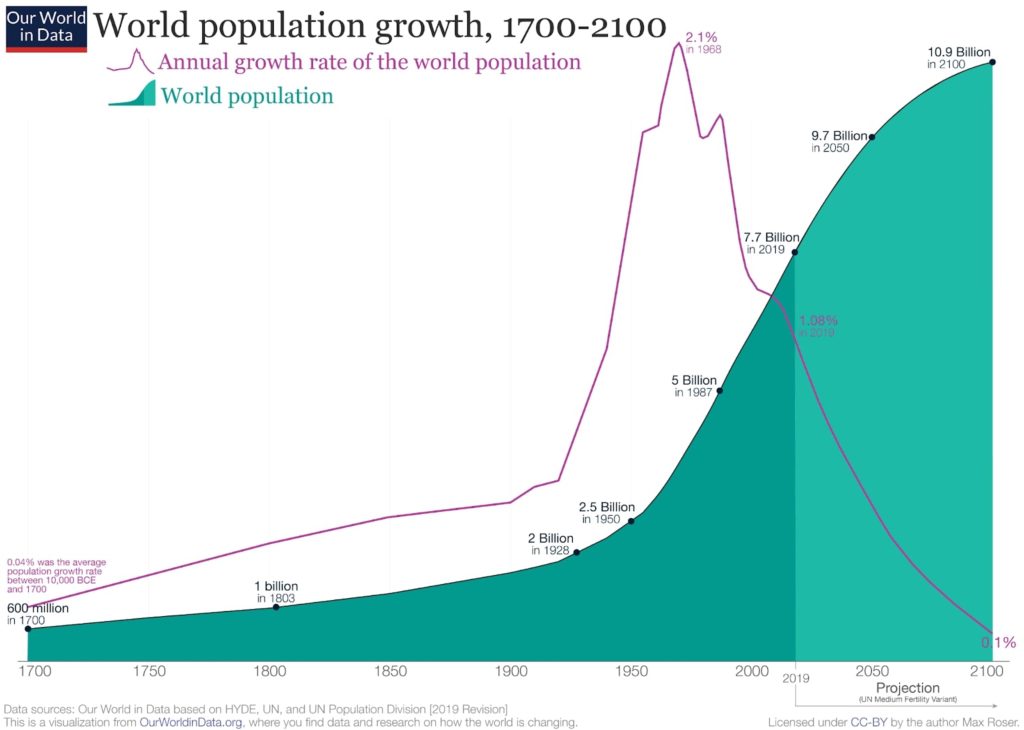

Figure 1: World population growth 1700-2100; Our World In Data. Data by United Nations; 2019.

The UN expects the world’s population to grow until around 2100 where it will peak and stabilise at around 11.2 billion. While this figure is certainly high, and likely to be adjusted in future, it does not spell our inevitable doom. A world with a population of around 11 billion would put little extra strain on the Earth’s capacity to provide, as long as we humans are able to change our patterns of high consumption and waste, without necessarily having to sacrifice quality of life. Technological developments, employing outdated agricultural techniques, reducing food waste and improving global distribution of resources would ensure that we could sustainably feed billions more. Wars, inequality and climate change are much bigger factors than populatoin numbers in determining a natural system’s capacity to support human life.

For instance, the Earth would be able to carry a much larger population if all of its inhabitants received their electricity from renewable sources, but would not be able to handle nearly as many if that population was entirely reliant on fossil fuels, given how the impactof climate change would affect resources. The effects of climate change will play a much larger role in determining whether the Earth is able to provide for its inhabitants, but population control measures have very little to do with countering climate change. The only way we can really do that is by ending our relationship with fossil fuels.

When Malthusianism intersects with political ideologies rooted in racial or social biases, ideas are proposed that may appear sensible on the surface, but the actual policy that accompanies them is nearly always based on a racialised approach to population control. These efforts generally seek to decrease population numbers of oppressed and poor groups in order to maintain the living standards and safety of wealthier groups.

These views were surprisingly common as recently as the 1960s and 70s, when the world was swept by a wave of overpopulation scares. American ecologist Garrett Hardin, who popularised the concept of the tragedy of the commons in 1968, also introduced the highly controversial idea of lifeboat ethics, which laid out a belief that it was morally excusable to “let struggling nations drown.”

Cloaking themselves in a perceived environmentalism and pragmatism, the policies that these ideas have historically led to have validated twisted and racially-motivated population control campaigns which eerily sound like eugenics. In the wake of the 1960s overpopulation scare, forced sterilisation campaigns were waged against Native American and Hispanic women in the US and Puerto Rico. In the 1970s, the Indian government forced millions of men from lower castes to participate in compulsory sterilisation programmes. If they did not comply, all social safety nets and government-assured rights would be essentially gutted.

While these dark legacies are not all tied to far-right political groups, they are tied to ecofascism, and the twisted brand of ecofascism that is resurging today is most definitely aligned with the alt-right. In the manifesto of the Christchurch shooter, Malthusian fears of overpopulation were directly addressed: “There is no green future with never-ending population growth, the ideal green world cannot exist in a world of 100 billion, 50 billion or even 10 billion people.” The El Paso shooter stated in his own manifesto that: “Everything I have seen and heard in my short life has led me to believe that the average American isn’t willing to change their lifestyle, even if the changes only cause a slight inconvenience. […] So the next logical step is to decrease the number of people in America using resources,” explicitly referring to non-white immigrants.

While it might seem harmless for political figures and other leaders to sound the alarm about overpopulation’s impact on the environment, these concerns can not only be wildly overblown, but can excuse and validate racist policies and heinous acts of violence.

Eco-fascism: What Next?

How do we minimise the voices of these resurgent fascist ideologies, while also combating climate change? The answer to this challenge is as complex as the reasons that caused it to emerge in the first place. Countless factors of our modern world- unregulated access to extremist content on social media and the ubiquity of alternative facts chief among them- have led to the formation of echo chambers online and in real life that only reinforce and embolden these dangerous ideologies, a trend that may have been exacerbated by the induced lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eradicating these ideologies from our streets will take time and effort. Eradicating them from the web more so.

But climate change does not care about your political leanings. Or your class, income, race, gender, nationality or religion. You could not believe in climate change at all, but it would still affect you, in fact it probably is already. To counter these divisive and dangerous ideologies, we must first separate the truths from the untruths, especially online where misinformation can spread like wildfire. We must then ensure that our institutions are bound to facts and are trusted by the public to act as educators. Extreme ideological positioning, left or right, has no place in the fight against climate change, and the energies and passions of people who fall victim to alt-right messaging need to be redirected towards real environmental progress.

To counter the dangerous rhetoric of these groups, we need to respond with action that proves them wrong. When right-wing leaning politicians lament increased rates of poverty and joblessness, they often blame overpopulation and immigration. People need to know that it is market failures and runaway capitalism that creates inequality, not too few resources for too many people. It is a mismanagement of natural capital that leads to environmental degradation and biodiversity loss, not immigration. And it is empowering women and supporting education and economic growth in poor countries that stabilises population numbers, not forceful population control.

As climate change creates increased scarcity over the coming decades, it is unknown whether wealthy countries will choose to hoard their resources or share them with the developing world. Will weathy nations passively permit climate change to fuel global migrations at an unprecedented scale, or will they finance adaptation measures in the developing world? Will nations with high resilience lock out everybody else, or will they recognise that doing so would only reinforce these abhorrent and extreme ideologies that never really went away? Accepting climate migrants and investing more in improving resilience in developing countries will be important acts of solidarity that not only acknowledge the past responsibilities of wealthy nations, but also work towards building a future more equipped to counter climate change.

What ecofascism and other extreme environmentalist ideologies fail to understand is that there is no rational argument for isolationism under the threat of climate change. Even if a wealthy country is able to reduce its own emissions, climate change will still affect it if it does not assist countries with fewer resources in doing the same.

There is some good news. People, especially young people, are increasingly inclined to band together in the understanding that climate change transcends boundaries. Today’s youth, and all the potential that it represents, cares deeply about climate change and the environment, probably more than anything else. Youth climate activism is global, and possesses one of the loudest voices. If governments can reduce the omniprescence of dangerous online echo chambers and promote education for all, people, especially young people, can find a sense of purpose in burgeoning activist movements that are actually helping to save the world. Violent extremism could be stripped of its most indispensable fuel: susceptible young minds.

Mobilising public and popular support to counter climate change is crucial to motivating legislators to do what has to be done, but they can also save imperiled youth from dangerous ideological positioning. This is only possible if governments ensure climate change messaging is clear and transparent. Shifting to a low-carbon economy is what will allow population growth to continue and eventually stabilise at a point where a much lower percentage of the world is living in poverty. Giving credence to unfounded overpopulation concerns and magnifying the grievances of extreme political ideologies gets us nowhere closer to solving these problems.

Featured image by: Flickr