Elevating women ranks among the most substantive measures governments can take to mitigate the climate crisis. Educating and empowering women can have a quantifiable effect on reducing a country’s emissions, and actively involving women in discussions on climate policy can often lead to much more impactful outcomes. The ecofeminist movement has for decades been highlighting how gender inequality intersects with the environmental crisis. The lessons we can learn from ecofeminism may hold the key to recognising how elevating women can help reduce emissions and create more equitable societies.

—

Ecofeminism first emerged in North American and European academic circles in the 1970s as an offshoot of the feminist movement, and specifically linked the subjugation of women to humanity’s oppressive relationship with nature. It was employed as a theoretical framework to better understand how hierarchical and dualist definitions of gender could explain humanity’s dominating role in its relationship with the environment.

Beginning in the 1980s, ecofeminism began to inform feminist and environmental activist and artistic movements. Heroes of the ecofeminist movement include several major intellectual and political figures. Françoise d’Eaubonne, a French author considered a leader in her country’s feminist movement, coined the name “ecofeminism” in 1974. Petra Kelly was a German politician who co-founded the German Green Party, the first political party with a predominately environmental platform to achieve national prominence.

By the end of the 1990s, ecofeminism began to come under fire from critics, who dismissed the framework as essentialist, in that it could not fully address either feminist or environmentalist concerns. Ecofeminism’s exclusive focus on the relationship between gender and nature left no room for considerations of other crucial factors, such as race or class. Janet Biehl, an American social ecologist, notably criticised the ecofeminist framework as an oversimplification of complex hierarchical structures and forms of domination.

What Exactly is Ecofeminism?

Today, the relevance and use value of ecofeminism has largely faded from activist and intellectual circles. However, the concepts behind the framework can still be applied to understand why elevating women can intersect with achieving equitable sustainability targets, and have such a measurable effect on mitigating environmental impacts.

Ecofeminism seeks to reexamine both the feminist and environmentalist movements and augment each of their arguments. The framework examines how gender and nature intersect, specifically how binary definitions falsely categorise opposing groups, assigning disproportionate value to one grouping and encouraging hierarchical thinking.

Binary definitions are used to easily distinguish between what is dissimilar. Within the context of gender, binaries are used to distinguish between male and female. When examining humanity’s relationship with nature, a similar binary exists wherein man-made creations are considered entirely separate from nature.

Binary definitions give rise to oppositional dualism, where one side is not only described as different from the other, but as its complete opposite, such as opposite genders. Ecofeminism claims that a similar oppositional dualism exists in conventional definitions of humanity’s relationship with nature. When humans look to develop further, natural environments are seen either as obstacles to be overcome or resources to be exploited. Within this framework, human development is seen as opposite to the preservation of nature. Urbanisation, for instance, necessitates environmental loss.

Oppositional dualism is complemented by the creation of hierarchical structures where cultures assign more value and power to one side of the binary. Ecofeminism sees hierarchies exhibited in gender relations through patriarchal social structures, and in relations with nature through an anthropocentric view that humanity is more valuable than nature and all other living beings.

An ecofeminist framework cites hierarchical thinking and oppositional definitions as reasonings behind the subjugation of both women and nature. These constructs can often justify masculinised acts of violence and domination towards women, animals and the natural world. These acts are often expressed through masculine cultural norms, such as hunting, domesticity and exploitation.

Ecofeminism was at a time quite popular in universities, but was never really able to break out of scholarly circles. The theory was also criticised for its shortcomings. By only considering the connection between women and nature, ecofeminism failed to account for the differences between individual women that can only be understood through more comprehensive frameworks analysing race or class.

In the 1990s, the environmental justice emerged as a framework employed by scholars and activists alike. Environmental justice refers to the fair treatment of all people, regardless of identity, in the development and implementation of environmental laws, and often addresses environmental concerns of direct relevance to society, such as pollution and food security. Environmental justice’s broad scope internalised what ecofeminism could not, and became the primary tool for a new generation of climate activists.

But in spite of environmental justice movement’s successes, its broad nature means that gender is rarely specifically addressed as a key to understanding the climate crisis and how to solve it. Highlighting gender inequalities and improving women’s access to healthcare, education and support resources has a measurable impact on reducing emissions and minimising environmental degradation. Studies also show that elevating women in legislative fields yields better outcomes in environmental policymaking, as well as more coherent efforts in international environmental cooperation. Despite its limitations, ecofeminism may provide a framework that addresses not only gender inequality, but also indicates what social stigmas need to be removed for nations to pursue more robust and impactful environmental action.

Ecofeminism’s Role in Elevating Women

Intersections between the environment and social issues are ubiquitous, although often overlooked. Resolving issues in one area can have a cascading effect on improving conditions in the other. For instance, decades of racist housing policies in Richmond VA, USA, limited investments towards improving living standards in neighbourhoods that were primarily home to communities of colour. Today, these neighbourhoods can be up to 8°C warmer than predominantly white neighbourhoods during summer, severely affecting health standards, especially for children. Understanding the structural reasons behind inequities can shed light on how these issues can be resolved, in this case by creating more urban green spaces and tree cover in these neighbourhoods to improve both environmental and health quality standards.

Failure to recognise the intersections between climate change and social issues damages the prospects of finding solutions to either. In the case of gender equality, elevating women through social initiatives, specifically improved access to healthcare and education, has a direct impact on reducing emissions by reducing a country’s total fertility rate.

Currently, the world’s population is around 7.8 billion. By 2050, the UN estimates that this will balloon to between 9.4 and 10.1 billion. Climate change solutions are tied to population; when a population increases, more food and energy need to be produced. Additionally, as populations in developing countries grow, so does their economic capacity, as more and more people are able to escape poverty and accumulate wealth.

Population growth accompanying economic expansion in developing countries is neither unnatural nor undesirable, although it will inevitably lead to higher individual carbon footprints and rises in nations’ overall emissions. To mitigate the environmental impact of population growth, states can pursue social initiatives that promise equal access to healthcare and education opportunities regardless of gender.

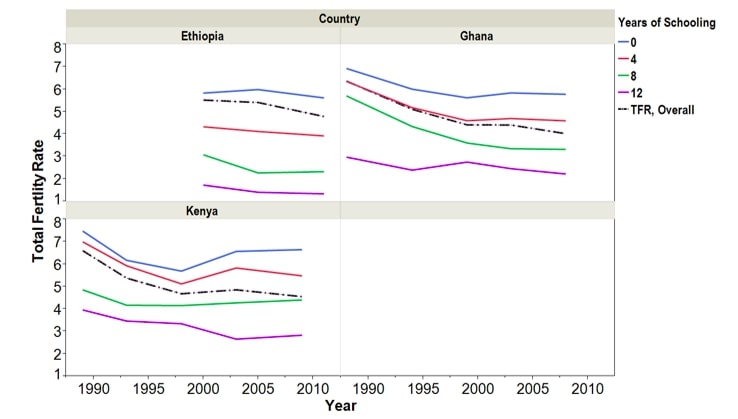

Where women spend more years in school, total fertility rates tend to fall. Studies worldwide show that improving access to education grants women more varied career options, the choice to delay marriage and ultimately have fewer, healthier children.

You might also like: How Some International Treaties Threaten Our Ability to Meet Climate Targets

Fig. 1: Relationship between female education and fertility rates in Ethiopia, Kenya and Ghana; World Bank; 2015.

Cultural, economic and health factors currently impede far too many women, particularly young girls, from attending school. The UN estimates that women make up more than two thirds of the world’s illiterate population, and that only 39% of girls in rural areas attend secondary education, compared to 45% of rural boys.

From a social perspective, improving literacy rates for women yields important benefits. Upward mobility and increased job opportunities can give women more agency to decide what to do in their lives, and are less likely to be forced into marriage or marry as children. Additionally, as literacy rates among women rise, income level, nutrition and child survival rates tend to rise as well.

Policies that can achieve these outcomes include making schools more affordable, granting girls easier access to healthcare and contraceptives, reducing the time and effort for youth to get to school and making schools safer spaces for young girls overall. Social initiatives that allow young girls better access to healthcare and education can empower and elevate women to make their own career and life decisions. This can have cascading positive effects on the environment by reducing total fertility rates over time. It is important that any social initiative addressing fertility rates or the roles of women not act as a form of forceful population control, such as a one-child policy, which can entail unintended and severe social consequences.

In addition to curbing population growth, improving women’s access to education can have a strong impact on sustainable resource management in economies reliant on agriculture. In many countries, women are responsible for the management of natural resources, including water, fuel sources and food. A 2015 study of communities in the Western Himalayas showed that women tend to be responsible for the conservation and management of critical natural capital, including forests, wetlands, wildlife and agricultural fields to supply basic needs for their families.

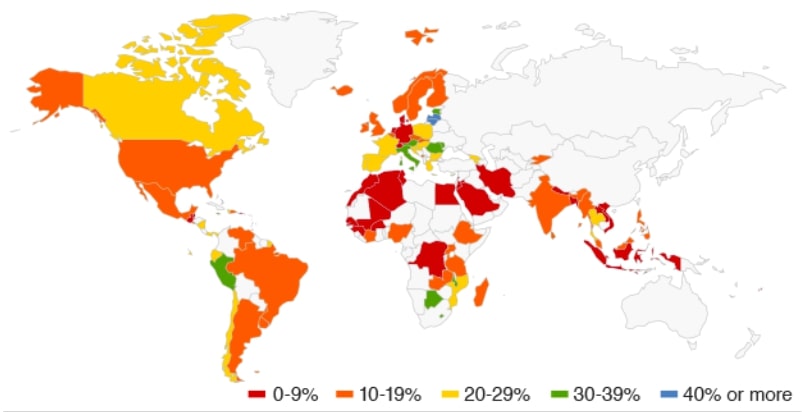

Another important factor to consider is that cultural barriers in many parts of the world currently impede women from owning their own land and securing loans or insurance policies. Globally, only 13.8% of agricultural landholders are women, despite the fact that 38.7% of employed women work in agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

Fig. 2: Percentage of agricultural land controlled or owned by women by country; FAO Gender and Land Rights Database, sourced by BBC; 2017.

These obstacles, combined with women’s roles as land managers and lack of access to education, make the effects of climate change, resource loss and agricultural failure significantly more palpable and dangerous for women than for men. In situations of poverty and resource scarcity, women tend to bear greater burdens than their male counterparts. A 2020 study demonstrates how traditional gender roles intensify and gender-based violence increases when climate change depletes natural resources and ecological services.

These inequities create what is called the agricultural gender gap. Because of cultural restrictions and economic limitations, women tend to produce less from the same amount of land as men and are forced into a low productivity trap. This leads to unnecessary demand for further land development and deforestation. Worldwide, if women farmers had the same economic and legal rights as men, global crop yields could increase by up to 30%, making agricultural production more efficient and limiting further environmental loss. In addition, closing the agricultural gender gap could save up to 150 million people worldwide from hunger.

The agricultural gender gap serves as an example of how social initiatives can yield positive environmental outcomes. Ensuring better access to quality education and healthcare, and therefore elevating women to become more active decision-makers in their communities, can be a uniquely effective force in economic growth and development.

The Importance of Women in Environmental Policymaking

It is critical for legislators to understand how social issues are linked to environmental impacts. Climate change does not affect people equitably, and policymakers need to understand how to account for these inequities with climate legislation that spurs fair socio-economic growth while tackling the climate crisis.

As in many political and decision-making spheres, women are alarmingly underrepresented in global environmental policymaking. Women hold only 12% of top national ministerial positions in environmental sectors worldwide. Combined with a lack of decision-making responsibilities granted to women in local communities, the voice of environmental policymaking has always been disproportionately male.

Elevating and empowering women should not stop at ensuring access to education and healthcare. Women should have their voices heard at all levels, and actively participate in environmental policymaking. Permitting women to do so tends to lead to more effective environmental policy outcomes.

Women have often been found to be more invested in social issues, including education, healthcare and environmental impacts. Research also indicates that women who hold an elected office tend to prioritise resolving tangible issues that directly affect other women, families and children. Given that women and children are disproportionately affected by climate change, women in politics have shown themselves to be more aware of environmental impacts, and integrate relevant solutions into their policy agendas.

Women in decision-making roles have also shown a higher proclivity for protecting natural resources. A 2015 policy brief catalogued women’s participation in local and national environmental policymaking in El Salvador, Chile and Vietnam. The report found that women are often in better positions to apply local knowledge to climate responses, and tend to prioritise preserving natural resources.

In addition to a predisposition towards strong domestic climate action, female decision-makers have also proven to be better negotiators and more likely to cooperate in international environmental pacts. A 2005 study found that, controlling for other factors, countries with a higher proportion of women in government were more likely to ratify international environmental treaties than other nations. The study also found that women in politics were significantly less likely to impose environmental and health risks on others.

There are a growing number of studies and reports worldwide that indicate how women tend to prioritise environmental protection and strong climate action. A 2014 Australian study found that women tend to consider environmentalism a stronger part of their personal identity than men. A study of US homeowners affirmed that women are often more conscious about the environmental footprint of the products they consume. A review of research done between 1988 and 1998 concluded that women have stronger environmental attitudes and behaviours than men, regardless of age or country of origin.

A 2021 study analysed the demographics of current environmental activists by surveying 367 respondents across 66 countries. The study concluded that the newest generation of climate activists skews female. Of the study’s respondents who were over 65, only one quarter were women. Of respondents under 25, two thirds were female. This trend reflects a demographic shift of climate activism. The newest generation of climate activists tends to be young, female and highly educated. Developed and developing countries alike need to harness these trends and elevate today’s female youth to become political leaders in the climate movement.

Fig.3: Age and gender demographics of climate activists across 66 countries worldwide; Boucher et al; Energy Research and Social Science; 2021.

Revisiting Ecofeminism

The ecofeminist movement attempted to define how binary definitions and hierarchical structures define gender relations and humanity’s relationship with the environment. Perhaps the theory was too far ahead of its time, as the disproportionate impacts of climate change on women could not yet be visualised.

Women are 14 times more likely to die from a climate-related disaster than men, and suffer disproportionately from resource depletion and consequential poverty. These impacts are caused by traditional gender roles that limit opportunities for women, and lacking access to education and healthcare services only exacerbates the issue.

While modern approaches such as environmental justice are able to broadly define how climate change affects different people in different ways, the relationship between the environment and gender can shed light on very substantive solutions to both issues, and should be addressed specifically by policymakers. Understanding the connection between the environment and gender is not only important because of the disproportionately gendered impact of climate change, but also because of the potential environmental solutions that can emerge by elevating women.

In addition to education, states must provide women with the resources needed to finance their own ambitions and pursuits. Microfinancing, a type of financial or crediting service that directly targets individuals and small firms that are otherwise unable to access conventional banking services, has proven particularly successful in elevating women in rural areas. Microfinancing can be provided by local communities, governments, NGOs or specialised microfinance institutions.

By empowering women and granting them equitable access to critical services, countries can improve their economies, improve the efficiency of their economic and material output and markedly reduce their emissions. Elevating women to actively participate in environmental policymaking at all levels also allows for a more determined and proportionate political voice.

A framework such as ecofeminism can help acknowledge how social issues and the environment are intertwined, and how solutions in one area can influence positive outcomes in the other. Where social inequalities and climate change intersect is often where the most impactful resolutions and policy measures can be found. Recognising where these intersections lie and how to meet them is critical to ensuring equitable sustainability and understanding humanity’s relationship with the environment.

Featured image by: Flickr