High-emitting companies and countries commonly use narratives and frames that downplay global warming. The psychological effects of the language that they use significantly influences public opinions and behaviour in their favour. As the climate crisis intensifies, reframing these deceptive narratives, using different words and storylines, is critical. Earth.Org takes a look at the evolution of climate communication in the past 50 years and current best practices.

—

During the recent 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, the summit’s president Sultan Al Jaber proudly presented the Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter, signed by fifty oil and gas giants that together contribute to 40% of global production. By signing the Charter, the industry pledged to achieve net zero emissions in their operations by 2050, though none pledged to cut production, which accounts for 80-95% of the industry’s total emissions. The commitment from the signatory companies diverts attention from what other countries are pushing for, which is phasing out fossil fuels and transitioning to renewable energy.

This is an example of a positive narrative – or frame – being introduced by high-emitters to portray themselves as heroes for pledging to do something good. While the deceptiveness of this particular frame might seem obvious, there are numerous seemingly innocent anti-climate frames introduced into the public discourse by high-emitters that even concerned environmentalists have unwittingly fallen for.

If we want to effectively combat global warming, we need to be vigilant and discerning about the language we use in the climate discourse, understand the underlying cognitive effects of these frames, and tear down misleading frames commonly used in climate communication.

Reframing the Climate Change Narrative

While the term “climate change” is used frequently, “global warming” has become less popular. The shift, however, was not accidental but rather a strategic choice.

In 2003, Frank Luntz, a communication expert working for the US Republican Party, introduced the term “climate change” into the public discourse. Upon his advice, Conservatives started using “climate change” instead of “global warming”, a more neutral term that does not necessarily have a negative meaning and urgent connotation to it.

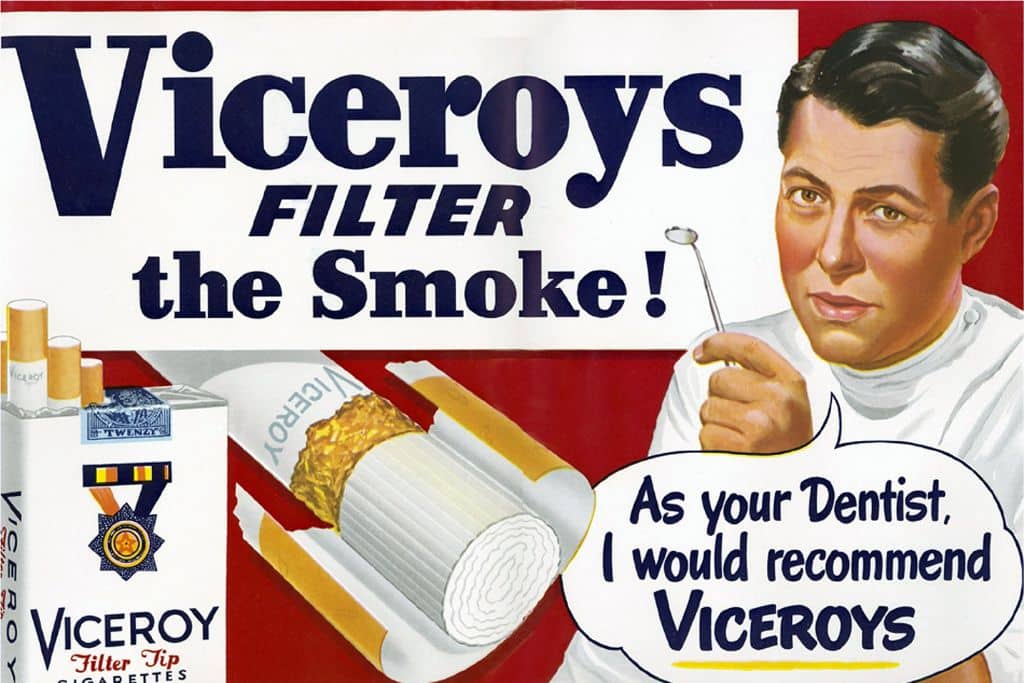

High-emitting companies such as fossil fuel company ExxonMobil copied this strategy and started adopting terms such as “climate risk” and words expressing uncertainty like “may”, “might”, and “potential”. These all suggest that global warming is neither a reality nor a certainty. Although in the 1970s, fossil fuel companies were among the first to learn about the reality of global warming, in the 1980s, they employed a group of influential, high-level scientists to use the strategy adopted by the tobacco industry a few decades prior to dismiss the harms of smoking.

Even though these ‘scientific experts’ did almost no original scientific work themselves, they were frequently seeking publicity to attack science that proved global warming and propose alternative explanations that were not scientifically proven. As they were often consulted by politicians and the media, they were successfully spreading misinformation for decades.

Slowly, the terms “climate change” and “climate risk” became the norm, not just among conservatives but among the wider population, leading to a disproportionate focus on discussing and proving whether climate change was actually a serious threat, as opposed to focusing on efforts and solutions that could effectively stop global warming.

Fortunately, with the climate crisis intensifying, new, more accurate terms started gaining popularity. Some of them are “global heating”, “climate crisis”, and “climate emergency”, all of which convey a sense of immediacy and alarm, and underlining the gravity, urgency and reality of the issue. Moreover, instead of talking about “saving the planet”, environmentalists began reframing the discourse to “saving humanity” or “saving society”, making the issue more personal and adding urgency to the matter.

Reframing the Plastic Recycling Narrative

A booming global trend and growing market is plastic recycling. Oil and gas companies, including ExxonMobil – a top producer of single-use plastic – have been actively promoting the idea that plastics can be recycled, despite being made out of petroleum or ethane (a by-product of oil-fracking). However, research indicates that approximately 91% of plastics cannot be recycled and the process of advanced recycling is not economically viable – issues the oil and gas industries are well aware of.

Plastic degrades each time it is reused. Most types of plastics can only be recycled once or twice until it becomes unusable. Moreover, pyrolysis, a common method used by advanced recycling firms that breaks down plastic under high temperatures, requires significant energy and generates toxic waste.

Sorting various types of plastic for recycling has become a challenge mainly due to the plastic industry’s successful lobbying efforts since the 1980s to place resin identification codes – recycling symbols with a number in the middle indicating the type of plastic – on all types of plastics. Initially, these codes were only used on plastics deemed suitable and easy to recycle, such as hard plastics (code one) and bottles (code two). Nowadays, the codes are seven, though most consumers are unaware about their real meaning, meaning most plastics still end up in the same bin, hindering any recycling attempts.

As a consequence, no more than 10% of all plastics have been successfully recycled in the past 40 years. Experts estimate that plastic production will triple by 2050, while most advanced recycling projects have failed, either scaling down or ceasing activity due to financial or logistical problems.

By introducing this plastic recycling frame, oil and gas companies convinced consumers that plastics are not harmful since they are recycled. As a result, they were able to hide the real impact of the plastic they produced while scaling up production.

Reframing the discussion on the repercussions that plastic has on society leads individuals to become more aware of the use of plastics and their recyclability. Recent research has focused on the dangers of microplastics and how these are being found in human food, bottled water, and even blood, though the impacts on human health are still being researched. Focusing attention on the health impacts of plastic provides a better narrative to the recycling discussion as it generates personal relevance to consumers. This frame creates more urgency to limit plastic production and has the potential to fuel more sustainable actions like pushing for a ban on single-use plastics.

You might also like: One Liter of Bottled Water Contains About 240,000 Plastic Particles, New Research Finds

Reframing the Greenwashing Narrative

As the public interest in climate action grows, high-emitting corporations have increasingly engaged in campaigns that promote sustainability for the sake of improving their brand and reputation. While these corporations market themselves or advertise their products as “green”, none of them are truly addressing global warming. This unethical practice is commonly referred to as greenwashing.

In greenwashing campaigns, words such as “green”, “eco-friendly”, “bio”, “natural”, and “sustainable” are often used misleadingly. The vague and unverifiable nature of these catchy terms make it impossible to determine how accurate (or inaccurate) these claims truly are. Greenwashing campaigns exploit this uncertainty, creating an illusion of environmental responsibility without real commitments.

The best way to counter these campaigns is to learn to recognise vague and unmeasurable catch-all terms. Consumers should only trust campaigns that back their narratives with certifications, statistics, measurable data, and verifiable examples. Any company that is unable to provide such details or is fabricating false narratives by wielding greenwashing, should be held accountable.

You might also like: 10 Companies Called Out for Greenwashing

Reframing the Carbon Footprint Narrative

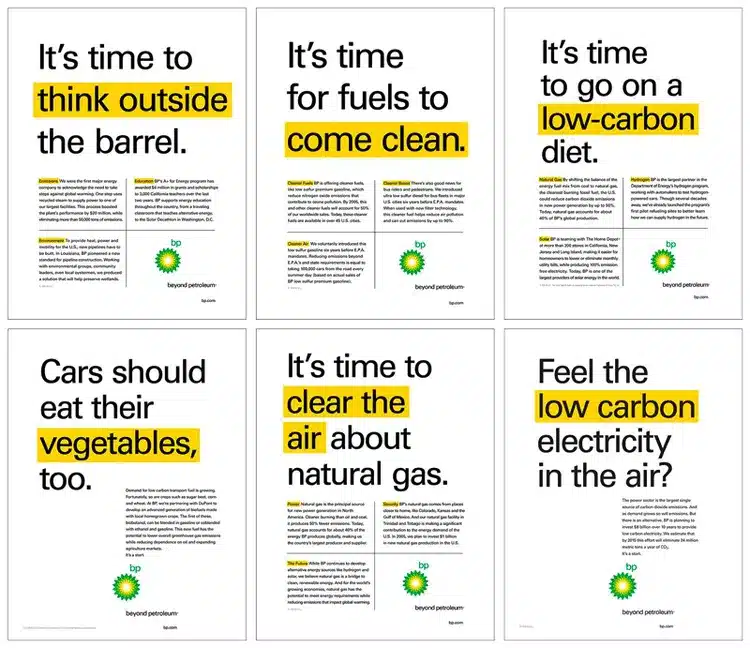

The concept of a carbon footprint has gained popularity in the global warming discourse. While it might come as a surprise, the term was popularised by oil and gas company British Petroleum (BP), one of world’s biggest emitters. In 2004, their public relations consultant, Ogilvy & Mather, had advised BP to introduce this concept in infographics and advertisements, along with a carbon footprint calculator. Other high-emitting oil companies, including ExxonMobil, and Shell, copied BP’s strategy and started sponsoring researches that assessed and compared the effectiveness of individuals’ sustainable actions, also frequently sharing tips on social media for citizens on how to be greener.

Using the term footprint – which literally refers to a trace left behind by a human being – subconsciously reinforces the idea that limiting carbon emissions can and should be done on an individual level, rather than by companies. The accompanying slogans from BP such as “it is time to go on a low-carbon diet” also reinforce this idea. The metaphorical word “diet” literally refers to a person or animal eating habits, which again implies carbon footprint is an individual concern, not of companies.

Reframing this narrative to focus on corporations rather than consumers is essential to let the public understand how emissions are generated. Individuals can become high-emitters simply because they buy high-emitting products or services. If high-emitting corporations are pushed to produce low-emitting products, consumers’ emissions will go down automatically. Hence, practices of corporations should have priority in the climate debate.

Linguistic Awareness Fuels Effective Climate Activism

High-emitting industries make use of seemingly innocent frames by underlying narratives that subconsciously downplay the gravity of the environmental impacts of their activities, often shifting the responsibility to consumers.

To avoid falling into rhetorical traps of deceptive climate frames, consumers should critically and consciously assess sustainability campaigns, projects, and products, such as carbon footprint calculators and plastic recycling initiatives, before supporting or promoting them. This requires investigating the institutions behind these initiatives, their operations, their true environmental impact, and the effect of the language and frames used.

Climate communication rules worth considering include avoiding to blame, criticise, or judge other people’s behaviours as this can cause individuals to end up in a state of numbness, resistance, opposition, or even anger. It is also important to realise that presenting a pessimistic scenario might consequently result in others ignoring the issue altogether. Rather than only focusing on how much money or lives will be lost, emphasise how much money or lives could be saved by investing in (rather than “spending money on”) climate mitigation and adaptation. Both the problem and the solution need to be framed in an attainable and manageable way.

This way, individuals can use language in their favour, calling out companies for their deceiving and polluting practices and ensuring that the situation our planet finds itself in is described in a manner that prompts much needed action instead of one that scares people away.

Featured image: Fossilfree London

You might also like: Bridging The Gap in Climate Change: Addressing Barriers in Communication to Save the Planet