Modern economic thought tends to attribute improvements in quality of life to economic growth, often equating wealth with prosperity. To this end, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been a critical tool to gauge economic success, serving as a measure of production and transaction over a specific period of time. The more goods and services that are produced and transacted in an economy, the wealthier that economy is. GDP has become a global standard in assessing economic performance, and therefore directly influences government policy and economic planning. However, GDP fails to address the negative impacts of externalities such as climate change and inequalities. How do economic growth indicators affect perceptions and policymaking concerning climate change, and what are the alternatives?

—

In any conversation on the merits and failures of GDP, it is important to distinguish it as a macroeconomic measure. Macroeconomics takes into account the activities of an economy as a whole, as opposed to microeconomics, which addresses the actions of individual people and firms.

Another important distinction to make is between wealth and prosperity. GDP is an effective metric to evaluate wealth, which is a measure of productive capacity and the amount of capital and material goods in an economy. However, GDP is not as effective when attempting to measure prosperity, which incorporates additional factors such as population health and happiness.

GDP addresses four different forms of spending on goods and services: consumer spending, government spending, investments that will maintain or accumulate value over time and a country’s net profits from exports.

GDP has proven effective at measuring figures such as productive capacity, tax revenues and inflation. However, by focusing exclusively on these factors, GDP can encourage economic trends in unsustainable directions. The metric’s fixture in conventional political discourse and economic thinking can severely skew government priorities, by ignoring external factors of extreme relevance to sustainability and quality of life.

GDP in the Age of Climate Change

How GDP interprets the impacts of climate change shapes governmental response and policy. GDP does not leave much room for factors other than transactional activity, and therefore climate change impacts are considered externalities, in that the effects of production and consumption on the environment are not considered in economic evaluations or market mechanisms.

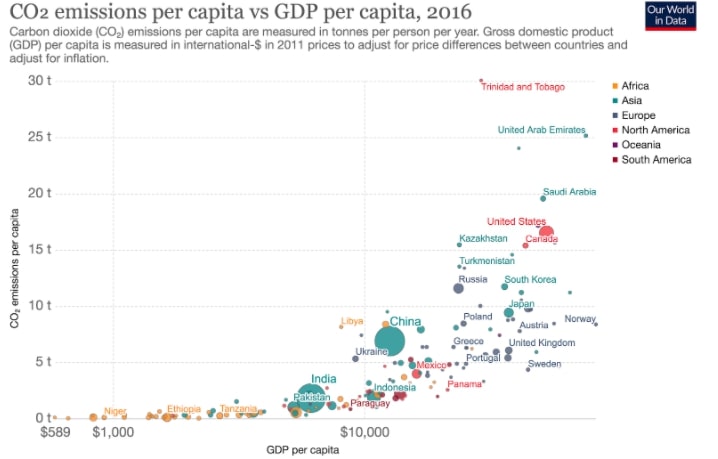

As indicated by the graph below, a higher GDP per capita generally indicates a higher rate of per capita CO2 emissions. This trend is symptomatic of classifying environmental impacts as an externality, as rising emissions are not defined as detrimental to economic growth.

You might also like: Trump Readies Last-Minute Auctions in Arctic Wildlife Refuge to Oil Drillers

Fig. 1: CO2 emissions per capita and GDP per capita; Our World in Data; 2018.

Without supplementary social progress indicators that can integrate externalities, GDP ignores factors that have devastating effects on social conditions. GDP does not highlight climate change, inequality and unhappiness as indications of negative economic and social development.

For instance, the US has one of the highest GDP per capita rates in the world, although the country’s average savings rate, the difference between a household’s income and consumption, is only 4.9%. In Hungary, with a GDP per capita less than half that of the US, the household savings rate is 9%. In this case, GDP is not accurately reflecting the factors that force most Americans into high expenses and live with fewer savings and more insecurities, skewing indicators of living standards and quality of life. By disregarding these factors, policymakers are not incentivised to pursue the meaningful change necessary to achieve prosperity as well as wealth.

From a Wartime Instrument to a Global Economic Index

GDP dates to the 1930s, in the wake of the Great Depression and at the onset of World War II. As economists worldwide sought to understand how to prevent future market failures, the theory of GDP emerged as part of a larger shift in economic thinking at the time.

The post-Depression era British economist John Maynard Keynes is famed for his lasting influence on macroeconomics. He opposed the concept of self-regulating markets and the notion of an ‘invisible hand’ that guided economic activity. Keynes believed that governments should increase spending and that overall amounts of spending, known in macroeconomics as aggregate demand, would be the best indicator of economic performance.

Keynes had a vested interest in developing a comprehensive measure of aggregate demand. In 1939, Keynes joined the British Treasury and was tasked with devising the country’s economic strategy to finance the country’s wartime needs. Upon taking on this role, Keynes encountered a dearth of information on the domestic production capacity of industries and the consumption needs of individuals. This meant that Keynes was unable to calculate exactly how much domestic industries would have the capacity to manufacture to support the war effort, and what amount of government spending could be reallocated to the military without sacrificing the basic consumption needs of the public. Keynes began calling for a more comprehensive measurement system for aggregate demand.

While Keynes made his arguments in the UK, similar opinions were forming in the US. Economist Simon Kuznets presented the earliest formal policy proposal of GDP to the US Congress in 1937. Kuznets’ model reconciled all economic production and transactions from individuals, companies and the government into a single value. Kuznets believed that as this value fluctuated, it would represent the performance of the economy. The model was intended to prepare the country’s resources for any eventual war effort.

When the war ended, countries began to see the value of cataloging their economy’s productive capacity. In 1944, the victorious Allied nations gathered at the Bretton Woods Conference, co-chaired by Keynes himself, to establish the new financial and monetary world order. The emerging methodology of GDP calculation would act as the foundation for the mandates of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, both of which were established at Bretton Woods.

These institutions are the most influential actors of the international monetary system, as they police international monetary cooperation and provide leveraged loans to developing countries. GDP plays a critical role in how these institutions evaluate economic progression and the status of developing countries, formalising the metric within the international monetary system. After China became the last major country to adopt GDP in 1993, the system became a pervasive global standard to evaluate and compare the performances of economies worldwide.

Concerns abounded over how GDP equated growth to welfare. In 1962, Kuznets himself bemoaned GDP’s seemingly directionless growth, saying, “Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between its costs and returns, and between the short and the long term. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what.”

Kuznets, like other economists, feared that economic growth policies would be purely for the sake of growth, and not for the betterment of countries’ citizenry’s tangible quality of life.

Concerns were dismissed by an overwhelming support for GDP by economists and politicians. An undeniable benefit of GDP lies in its linearity and simplicity. GDP only requires a simple aggregate of transactional activities in an economy, and its status as a globally used indicator optimises the efficiency of economic cooperation and evaluations. The notion that spending patterns accurately reflect economic performance was at once comforting and appealing to economic purists.

GDP & Sustainable Development

While GDP functions as an effective calculation to measure the total productive output of a country, it can oversimplify the experiences of individuals and obscure inequalities.

The impact of economic growth on falling unemployment rates is a favourite talking point for GDP advocates. In 1962, American economist Arthur Okun crafted what is now known as Okun’s Law, an empirical observation on this correlation. The rule, as defined by Okun, established a statistical relationship between a rise in GDP and a fall in unemployment.

Fixating on perennial job growth and low unemployment is problematic for a number of reasons. In developed economies, unemployment rates generally do not reflect the workforce participation rate. Low unemployment rates can also indicate a lack of productivity, or slack. GDP encourages governments to focus on job growth, without taking into account the types of jobs being created.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, the US boasted one of the lowest unemployment rates in history, however fewer than 50% of American workers felt satisfied with their job. GDP incentivises these objectively negative trends, and discourages governments from pursuing more ambitious policy measures that can improve quality of life and reduce slack in developed economies. Examples include making education more accessible and creating the conditions and safety nets wherein individuals can transition to more meaningful and productive work without facing financial hardship.

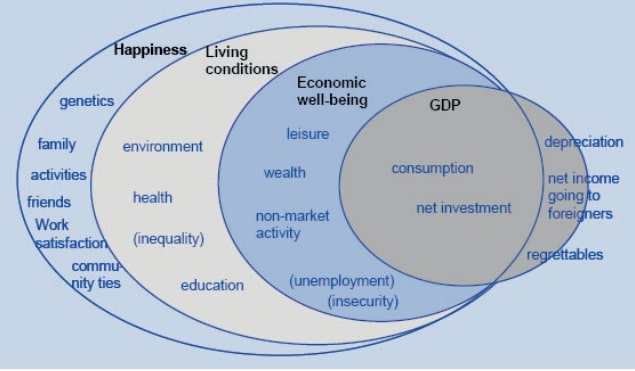

Fig. 2: The many elements of happiness and well-being, Deutsche Bank Research; 2006.

GDP has become such a pervasive influence that recessions and economic peaks and troughs are all defined by it. Given its importance, policymakers in developed and developing countries attempt to make their country’s GDP appear as strong as possible.

Despite its relevance in policymaking, GDP also fails to address certain critical sectors of an economy, such as the value generated by the informal economy. Additionally, GDP only incorporates the final transactional value of a product, and not the value of work done during the various production steps, the value of that product’s raw materials or the impact of extracting them. When GDP fails to account for critical sectors of an economy, the perceived performance of that country’s economy tends to become inflated and misrepresentative of quality of life.

This characteristic of GDP can be especially damaging in developing countries, where most of the workforce participates in the informal economy. An informal economy includes all economic activity that is unregulated and untaxed by the government. This can include black market activity though for the most part refers to self-sufficient economic transactions such as selling independently grown fruit on a street corner. When the majority of a country’s workforce is not represented in GDP calculations, it becomes problematic when all economic policy decisions are made with GDP numbers in mind.

Multinational corporations can also skew GDP numbers and hamper development in low-income countries. When major corporations cheaply extract resources from developing countries, the activity is registered as an economic boon for the country in GDP terms. However, the country’s resources will normally be exported and consumed in developed countries, and while these activities are often taxed, the lion’s share of dividends and profits will primarily be enjoyed by the corporation, not by the developing country’s population. Multinational operations in developing countries can sometimes lead to job creation, however this is often not the case, as seen with China exporting its own workers for its Belt & Road Initiative. Growth in GDP and perceived performance of the economy does not naturally lead to material improvement in the quality of life of a country’s citizens, who will now be burdened by a dependence on foreign actors and environmental degradation.

The Economics of Disasters

GDP favours high spending from consumers and governments. While differing political and economic ideologies will disagree on how much each group should contribute to overall spending, the ultimate goal is to have a high rate of consumption and expenditures. These are the key factors to keep in mind when discussing the effect of GDP on the environment, and how the macroeconomic interpretation of climate change as an externality affects government response.

Viewing the impacts of climate change through a macroeconomic lens that only focuses on production and consumption is short-sighted and unsustainable. Similarly to how GDP does not account for job satisfaction or quality of life, the impact of climate change on individuals is left unaccounted for.

Take natural disasters. Climate change is exacerbating the frequency and/or intensity of natural disasters including wildfires, tropical storms and floods. Natural disasters incur a tragic human cost, be it loss of property, livelihood or life. However, in terms of GDP growth, the impacts of natural disasters as a result of climate change can often appear as positive.

Studies have shown that economic output and GDP are often unaffected or higher after a natural disaster strikes. In these circumstances, government spending increases as disaster relief programmes are enacted, and the rebuilding of infrastructure with more modern technology creates new construction jobs. Consumer spending also increases due to insurance policies spent on replacing lost property. Investments and net exports will presumably fall slightly, however the substantial increases in consumer and government spending will indicate GDP growth.

This characteristic of economics was first noted by the French economist Frédéric Bastiat as early as 1850, in what Bastiat termed the ‘parable of broken windows,’ or the broken window fallacy. In the parable, a boy breaks a window, and his family pays a window glazier to have it replaced. In the eyes of society, the entire process is a net positive for the economy and therefore desirable, as a broken window allows the glazier to earn a wage which will continue to be circulated in the economy. Bastiat notes that the activity that society endorses is economically equivalent to the glazier paying the boy to deliberately break windows so he can repair them. While the boy’s actions stimulate circulation of capital, the long-term implications of the broken window are hidden. The boy’s family loses some of their disposable income and will be unable to purchase something they needed before the window was broken. If, say, the father had planned on buying a new pair of shoes with the money, the shoemaker will now have lost a sale due to the broken window. Additionally, the cost of repairing the window is a maintenance expense that does not improve the family’s quality of life relative to before the window had been broken.

The broken window fallacy has been used to describe the opportunity costs of disasters and other climate change impacts. While relief programmes will stimulate the economy and provide jobs in the short-term, a myriad of unintended and unknowable consequences of the redirected capital will exist. Had the disaster not occurred, the government could have spent its money elsewhere. The quality of life of those affected by the disaster has also not improved, since expenditures only replace lost or damaged property, comparable to the maintenance expense of repairing a broken window.

GDP ‘s interpretation of climate change is similar. By categorising environmental impacts as externalities and focusing on output and production, economic foresight is limited. GDP also fails to account for the very real human cost of climate change, namely the loss of life or livelihoods that are difficult to appropriately quantify. While climate change can induce growth as far as GDP is concerned, it elicits a considerable loss of social welfare and well-being.

Consumption & Development Priorities

High consumption invariably precedes waste, as policy focused on GDP growth necessitates a preference for consumable rather than durable goods. Durable goods, which are designed to last and be purchased infrequently, do not encourage high consumption. Conversely, consumable goods not only need to be purchased more often, but require mass production and raw material extraction, creating more jobs and increasing economic activity. Consumable goods are also cheaper to produce on a mass scale, do not require a skilled workforce to manufacture and can capitalise on dynamic social and market trends.

The popularity of consumable goods has permeated most aspects of the market through planned obsolescence, the practice of manufacturing products with a purposefully limited lifespan before they need to be replaced. For instance, the fashion industry, which accounts for 10% of the world’s annual CO2 emissions, has devolved into fast fashion to encourage higher consumption, accounting for 21 billion tonnes of textile waste each year. Tech, automotive and electrical goods manufacturers also tend to market a new iteration of their products every few years. It is estimated that the toxic e-waste generated by these industries accounts for 50 million tonnes annually.

Despite its environmental impact, planned obsolescence plays an important and even positive role in a social and macroeconomic context. Companies can justify employing a large workforce, and the mass production of cheap goods grants people of all income levels and in developing countries easy access to products that measurably improve quality of life. Without cheap consumables, people and countries with fewer resources would not be able to enjoy many basic amenities.

This highlights the positive role GDP can play in developing countries, where economic growth does often equate to improving quality of life through the emergence of a middle class. The formation of a working middle class can elevate people from poverty, and certainly leads to an increase in consumption due to higher wages, but also to vastly improved living standards. Some ethicists argue that the costs of removing the benefits of higher living standards through economic growth in developing countries would outweigh the impacts of climate change on these countries.

This is not to say that there is a universal rule stipulating that the benefits of unabated economic growth will always outweigh the benefits of mitigating ecological degradation for a population’s living standards. A 2010 paper found that, in developing countries undergoing regime changes, life satisfaction improvements reflected GDP growth for the first ten years of transition. In developed countries with stable regimes, there was no relationship between GDP and life satisfaction changes.

These findings indicate that GDP and economic growth can be a good indication of quality of life for developing countries with a growing middle class. However, the correlation dissipates as growth stabilises. Including environmental quality and public happiness in progress indicators is certainly desirable, although only realistic, and arguably ethical, when a country has already reached an apposite standard of living, wherein most of its citizenry is able to feed itself and possesses adequate shelter. Prosperity is unachievable without prior wealth. GDP has a role to play when discussing development policy and transitional economic planning. The issue is that developed countries have not expanded economic indicators to address additional quality of life factors when welfare growth begins to plateau.

GDP has acted as a universal indicator of economic performance for decades, creating externalities and consequences that are unaccounted for. GDP should not be discarded completely, rather, governments must understand how to incorporate what is missing into standards of economic success.

Supplementing GDP

As far as GDP is concerned, objective tragedies such as natural disasters or terminally ill patients with high medical expenses are considered positives for economic growth, simply because money is exchanging hands. The goal should be to demystify the perceived exclusivity of the relationship between progress and economic activity.

This can be accomplished by integrating externalities through social progress indicators that enhance the capabilities of GDP. While effective in isolation, GDP is ultimately an arbitrary calculation that emerged out of governments’ concern as to whether they were in an economic position to go to war.

Externalities can be integrated by incorporating the social and environmental costs of economic activity. As an example, if a family were to hire someone to take care of their newborn, GDP would rise. If, however, either parent decided to stay home and take care of their child, this activity will normally cause GDP to fall.

While the second scenario entails a drop in the economy’s productive output, it yields a higher social benefit, as parents would be able to spend more time with their child, which has been shown to result in higher academic achievement and mental health outcomes for youth. An adequate economic performance metric in a developed country would ideally integrate social progress figures that indicate well-being, including rates of school completion, academic performance, divorce, mental health, substance abuse, civic engagement and environmental quality. The Social Progress Imperative is a global NGO that evaluates countries based on measurements of quality of life. The initiative employs a scorecard that expands upon three broad areas of social progress.

Figure 3: Framework questions for Social Progress Index 2020, Social Progress Imperative; 2020

Governments can use a social progress index in conjunction with GDP to understand how to remedy market failures from an environmental and social perspective. By integrating the costs that GDP treats as external, such a metric could reliably reflect the circumstances of people in a society. Some countries have incorporated these indicators into their growth metrics. Bhutan, for example, employs a Gross National Happiness index, which is guided by Buddhist teachings and measures factors such as physical and mental health, ecological diversity and community vitality. China has also attempted to implement a ‘Green GDP’ system that monetises environmental damages and climate change impacts. Other countries have developed a number of GDP alternatives that have been implemented to varying degrees of success at local community levels.

A social progress metric would be able to more accurately value goods and services based on their environmental and social impact, by highlighting the externalised costs imposed upon society. An example is the meat and dairy industry, which is the third largest contributor of global emissions. While meat and dairy is often relatively cheap for consumers in developed countries, this is often due to high government subsidies and externalised costs. In the US, the government spends $38 billion annually to subsidise the production costs of the meat and dairy industry, while spending only 0.04% of this on fruits and vegetables subsidies. Considering subsidies, healthcare costs and impact on the environment, animal producers impose a total externalised cost of $414.8 billion on American society. Healthcare costs account for $314 billion. A social progress index would be able to incorporate the associated healthcare costs and reflect the unsustainable nature of the industry.

Other environmentally and socially damaging sectors, such as the fossil fuel industry, are heavily subsidised by governments and incur high healthcare costs. If these costs were accounted for in economic growth indexes, governments would have a more complete picture of their economy.

If subsidies were moved to support the endeavours of sectors that are not actively depleting natural capital and harming the environment, goods produced sustainably and with a low carbon footprint would become more affordable for consumers. A more complete economic metric can place higher market value on the production and purchase of sustainable goods and services, incentivising producers and retailers to focus on these products. Long-term benefits for consumers would include lower taxation, as externalised costs such as healthcare would now be holistically addressed by economic policy. Such action can integrate externalities in a way that more accurately reflects the social and environmental costs of unsustainable economic activity.

Individual countries at different stages of development can also adapt social progress indicators to more accurately identify their needs. For instance, while a developing country still working to grow its middle class and economic capacity might not be able to focus on mental health or substance abuse treatment, it can integrate education completion and child malnutrition rates into metrics assessing economic growth.

To achieve truly sustainable growth and an economy that works for its people, GDP will need to be supplemented with other measures of social progress. By dismissing the incorrect assumption that sustainable welfare growth is inextricably tied to GDP growth, a more accurate socio-economic picture forms. If governments strategically select where to place their subsidies, goods and services with a lower environmental cost can become highly valued on the market. By changing the parameters by which we measure economic performance to properly reflect the importance of environmental quality and social well-being, governments can be incentivised to pursue meaningful policy action.