Extreme weather events as a result of the climate crisis have resulted in resource scarcity and famine. The Syrian civil war that began in 2011 (that is still continuing) has caused more than 5 million ‘climate refugees’ to move to Turkey and neighbouring countries. The root of this war can be traced back to the drought the country experienced before 2011. How is the climate crisis related to extremism?

—

Climate Change and Extremism

Lack of food, water and other resources has created opportunities for militant and extremist groups to seize control of resources and exploit them to get recruits to join their ranks in exchange for work and food. This strategy has been found to be used in extremist groups in North Pakistan, Syria, Iraq and West Africa, which experience extreme water stress and famine.

The MENA region is home to 6% of the global population, but only 1% of the world’s freshwater resources, according to the World Bank. Some experts believe that drought played a role in sparking Syria’s civil war. The prolonged drought led to the death of 85% of livestock in eastern Syria and widespread crop failure, which pushed 800 000 people into food insecurity and triggered mass migration, contributing to civil unrest.

A 2017 report commissioned by the German foreign office claimed that the impacts of the drought were also linked to the growing influence of ISIS in the Middle East. According to the report, ISIS ‘tried to gain and retain legitimacy by providing water and other services to garner support from local populations’ during the prolonged drought.

According to experts, the diminishing water sources are ‘flashpoints for violence‘ as communities struggle with reduced crop yields and high levels of poverty. Extremism is sometimes the only option available.

However, other researchers have disputed how much of a role drought played in the conflict.

Further south, across the Sahel region, the impact of the climate crisis is shown by the shrinking of Lake Chad. Spanning seven countries, including Nigeria, Niger and Cameroon, the lake is vital to the likelihoods of nearly 30 million people. However, the lake’s water supply has shrunk by over 90% since the 1960s, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Robert Muggah, who analyses global climate and security challenges at the Igarape Institute, a think tank in Brazil, claims that the drying of Lake Chad has bolstered recruitment efforts of groups including Boko Haram, the militant group operating in Nigeria.

This strategy was also used during the Great Depression in the US in the 1930s, where Mafia leader Al Capone ran a soup kitchen for poor people in Chicago as a way to gain support from blue collar workers and recruit members into the ranks of the mafia when the government failed to give them sufficient support. In Morocco, a report found that the more tyrannical and corrupt the government, the more extremist activity that occurred.

Ultimately the rise of extremism is the result of government mismanagement and failure to deal with a crisis. In the case of the climate crisis, many developing countries do not have the resources or technology to adapt or mitigate the impact of it, which leads to rebellion and social unrest. Further, when these climate refugees move to other countries (usually developed Western countries), clashes in ideology can also lead to extremism.

Many leaders gearing towards extremism, like Osama bin Laden, included environmental issues in his propaganda to recruit supporters. The group used the West’s failure to act against the climate crisis through the exploitation of natural resources in developing countries as a way to recruit people. However, some militant groups also finance their activities through oil extraction, illegal logging and mining, and other environmentally destructive activities, exacerbating the climate crisis and further destabilising developing economies.

This unending cycle has caused many people to be displaced and forced to migrate elsewhere. Host countries often view these migrants as economic migrants or asylum seekers, however if it was considered that the ultimate root cause of these migrations was climate change, perhaps the conversation around the issue would be different, one that prioritises getting to the root of the problem instead of the end result.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines two types of climate refugees: ones that are created through sudden and temporary environmental changes, such as hurricanes and floods. However, more often than not, those that are affected will return to their homes. The other type of climate refugee is the pressured environmental migrant, that is created through the long-term gradual change in environment such as droughts, desertification and sea level rise.

Positively, there are some countries that foresee the impacts of the climate crisis and are acting to mitigate its effects. The low-lying Pacific country of Kiribati has purchased land in Fiji to prepare for the migration of its population of over 100 000 people should sea level rise render the nation uninhabitable. The majority of the land of the island is below 2 meters above sea level which, in addition to increased frequency of storms, has contaminated the atoll’s groundwater. The country has determined that it will be cheaper to relocate than to protect the island against sea level rise. A similar relocation strategy has been considered by the Maldivian government, who pledged in 2009 to become the world’s first carbon-neutral country.

Nations that will be most affected by the crisis would be remiss not to have the same considerations.

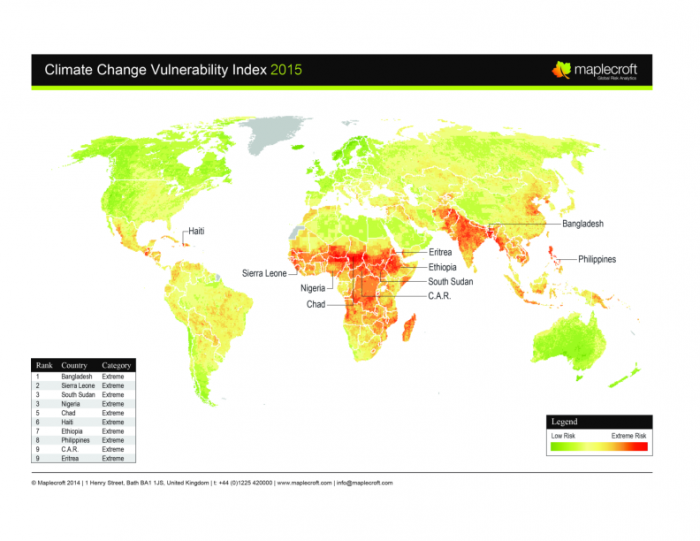

The climate crisis also highlights inequality, called the climate caste system, whereby poor people and nations suffer the most from the climate crisis while wealthier people and nations suffer less, while emitting the most carbon. The Climate Vulnerability Index summarises regions in the world that are most vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis by calculating the development level of the region and the climate change impact. The index found that the Sahel region in Sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia and Latin America all have a high risk of climate vulnerability.

Solutions?

A study found that relative to a world that did not warm beyond 2000-2010 levels, there will be reductions of 15-25% in per capita output by 2100 for 2.5-3°C of global warming implied by current national commitments, and reductions of more than 30% for 4°C warming. The IPCC found that the cost of stabilising CO2 to 445 ppm would correspond to ‘slowing average annual global GDP growth by less than 0.12%’.

The study emphasises that the uncertainties surrounding the future impacts of the crisis include the spatial pattern of temperature change, how global and regional economic output will respond to these changes in temperature and how willing societies are to trade present for future consumption. Humanity needs to change their patterns of consumption to avoid catastrophic consequences. The cost of inaction will only increase every year, demanding immediate action.

The climate crisis acts as a multiplier, especially in fragile countries held by weak governance, poor economic perspectives, food and water scarcity and failing local institutions. To effectively address the crisis, large consumer countries must invest significantly in sustainable alternatives and adaptation programmes, even if it opposes political and economic interests, which will reduce people’s vulnerability to extreme climatic events. The wealth gap between developed and developing nations needs to be narrowed if extremism is to be tackled.

Countries must become more climate resilient through diversifying crop production and investing in renewable energy, especially in Africa and the Middle East. Muggah says, “By strengthening and empowering local residents, the influence of extremism can be weakened.”