We are beginning to recognise the climate crisis as a real and emerging problem around the world; but for some communities this has been detrimental to their ways of life for decades. In the Arctic, temperatures are rising far more rapidly than many of us can imagine, and is leaving Indigenous peoples with melting homes and a decrease in food supply. Indigenous climate justice tackles not only are the physical impacts of climate change detrimental to some Indigenous communities’ survival, but the lack of recognition of their important traditional knowledge and cultural links to the land have left them facing huge injustices.

—

In 2013, a group of Indigenous peoples attended an anti-fracking protest near New Brunswick, Canada, when the police intervened. When Amanda Polchies, a Mi’kmaq woman of Elsipogtog First Nation, witnessed pepper spray being fired at elders, she ran to the front of the crowd, held up a feather and began to pray. Little did she know that an Inuk journalist, Ossie Michelin, photographed the interaction and the image was later named best photograph in the museum’s Points of View: A National Human Rights Photography Exhibition.

Climate-induced changes have exposed and exacerbated social and economic inequalities, especially in marginalised communities. Though each community’s experiences are nuanced, Indigenous peoples in the Canadian Arctic are witnessing the losses of the natural world while contributing next to nothing to the phenomenon that is causing the destruction.

Climate policies and “solutions” can also result in disproportionate impacts throughout different communities, and even exacerbate structural inequalities and injustices.

Today, the term climate justice is used by researchers, NGOs, and politicians pursuing ways to address climate change while also considering the social and economic inequalities throughout society. In other words, climate justice aims to reshape climate action from simply finding ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, into an approach that simultaneously addresses structural elements, human rights, and inequality.

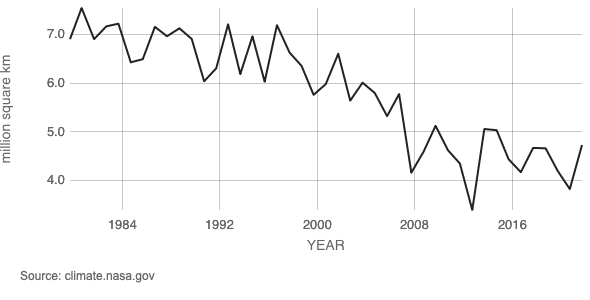

The Arctic is experiencing transformative climate impacts, as scientists believe that the region is warming between two and three times as fast as the global average. Although the physical impacts of climate change are continually reported (such as species extinction, sea level rise, melting permafrost, and a northward-shifting treeline), the socioeconomic effects on marginalised Indigenous communities are often missed in reporting.

The catastrophic impacts of climate change, compounded by ongoing notions of colonialism, have impaired Indigenous peoples’ abilities to maintain their physical health due to inabilities in completing subsistence-oriented hunting and fishing. Mental health within the communities has also suffered with the destruction of intrinsically valuable cultural and emotional connections to land, and the loss of traditional Indigenous Knowledge. This has been reflected in the increased suicide rates throughout Indigenous communities in the last decade.

The protest in New Brunswick was not an isolated event, and simultaneous efforts of Indigenous-led movements addressing environmentally destructive infrastructure is becoming more prevalent (have you heard of the Alberta Oil Sands, or the Alton Natural Gas Storage Project?). Large corporations are continuing to implement infrastructure projects that exploit the natural environment and amassing huge wealth from it, yet marginalised Indigenous communities are paying the excessive price of experienced grief and loss for these constructions.

Canada’s pact for a Green New Deal launched in 2019, with ambitions of increased renewables, green jobs, oil sands phaseouts, and Indigenous reconciliation made a priority. Yet, the disproportionate exposure of Indigenous peoples to hazards from low-carbon “solutions” seemed all too familiar. For example, the Muskrat Hydro Dam (labelled a “project of death”) is predicted to flood over 100km of the Peace River that holds cultural importance for numerous Indigenous traditional territories.

The need for recognising the importance of broader sustainable development goals when addressing climate change in the Arctic is more pronounced than ever before. Only recently have Indigenous peoples been given access to participate in the mechanisms through which they can influence research and governance in the region. For example, the participation of Indigenous organisations through international governance bodies (like the Arctic Council) has resulted in a few small wins for Indigenous climate justice. These are the communities that have witnessed the changes in their surroundings first-hand and can offer important considerations of resilience and adaptation methods, with the help of collaborative approaches.

Researchers are also collaborating to introduce participatory methods that include Indigenous peoples in meaningful discussions about the future of their territories, and how sustainable practices and policies can be adopted to sustain the environment. Instead of being simply ‘consulted’ in these huge decisions, Indigenous peoples need to consent to the projects – it is they who are relocated, their sacred lands destroyed, and their culturally important food and the knowledge that goes with it that is being gradually removed.

Understanding the key causes and mechanisms by which climate injustices take place is important in changing the norm. While Indigenous peoples are increasingly being given a voice in decision-and policy-making, institutions, corporations and Western mindsets continue to create barriers to the success of meaningful initiatives. Though decarbonisation is important when addressing climate change, a decolonial approach to climate governance is important in recognising the importance of Indigenous perspectives when enacting real change.

To learn more about indigenous climate justice, start by hearing the stories from Indigenous peoples themselves. Here are a few resources:

- There’s Something in the Water covers environmental racism and the exploitation of marginalised groups in Nova Scotia, Canada.

- On Thin Ice is an NBC documentary on climate change and Arctic indigenous communities.

- Although Albert Wiggan discusses Australian Indigenous communities in this TEDx Talk, it provides a thought-provoking perspective on interpreting and valuing Indigenous knowledge as science.

Featured image by: Leneisja Jungsberg/Nunataryuk (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)