In an affluent economy, moderate inequality is to be expected. Inequality can theoretically enliven slow-growing economies, and provide substantial incentives for individuals and firms to pursue new and exciting opportunities. But without thoughtful regulation and government intervention, our late-stage brand of capitalism has taken inequality to new extremes. Deepening wealth and income inequality in advanced economies has led to weaker democracies, poorer health conditions and inescapable economic traps dependent on the station of one’s birth. But in addition to the dire social consequences, could extreme inequality also be accelerating the degradation of our environment?

—

The Economic Policy Institute in the US estimated that, between 1980 and 2015, income for the top 1% of earners in the country increased five times as fast as the bottom 90%, and similar trends have been observed in the EU bloc. The rise in income inequality in wealthy countries around the world has been one of the defining trends of recent decades, because while governments have been relatively successful in tackling economic challenges such as reducing extreme poverty, widening income gaps have never received the same attention.

Extreme inequality can emerge for a number of reasons, including lack of legislation protecting workers or processes such as automation constricting job markets. Income inequality becomes pervasive when the wages on offer for low-income professions fail to increase sufficiently over time, while wealthier groups are able to accrue and retain more wealth. In an economy with high income inequality, some people have vastly more than they need, while others remain mired in poverty and deprived of any discernible wealth, lacking access to adequate housing, healthcare or education.

You might also like: Making the Case For a Green Investment Bank for Hong Kong

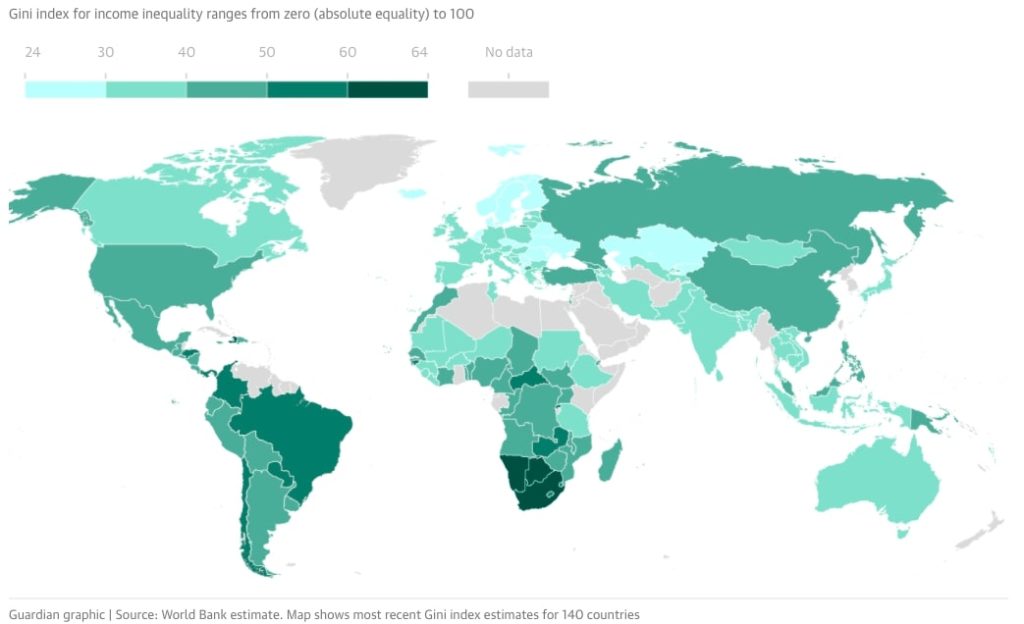

Figure 1: Economic inequality in 2017 based on GINI Index. A higher GINI score indicates higher rates of inequality; Data from World Bank, visualisation by The Guardian; 2017.

The social impacts of extreme income inequality can be severe. In an unequal society, the wealthy few could easily convince themselves that they earned their fortunes and are fully deserving of their enormous wealth, developing attitudes of privilege and perceived entitlement over others. Likewise, the many poor who are continuously and fruitlessly struggling to escape poverty may develop feelings of inferiority, resentment or even hostility. Extreme inequality can distort how a society identifies itself, and can negatively affect how individuals within it interact with one another.

But social consequences are just some of the detrimental effects inequality can have. What happens when people are driven to extremes, and their identity is stripped to be replaced by the demands of a hypercompetitive economy where more and more people are unable to afford basic needs and services to survive? Society at large certainly suffers, but a consensus is emerging that the environment is an oft-forgotten but no less affected victim of inequality. Why does inequality inevitably seem to precede environmental destruction, and is there a way we can solve both challenges simultaneously?

Not All Footprints Are Created Equal

The more an economy is based on a consumer culture of constant buying, the heavier its carbon footprint will be, since more buying will generate higher emissions from industry and produce larger amounts of waste. For economies that base their success solely on GDP and how much is materially consumed within them, emissions and carbon footprints tend to be correspondingly high.

So what is the relationship between inequality and high consumption? On the surface, the assumption could be that stagnating wages for the majority of society would lead to people having less disposable income to buy things, thereby lowering consumption and environmental degradation. But the reality is a little more complicated.

First, widening income inequality does not only entail a loss of income for poorer households, but also a transfer of income from the population’s poorer majority to its wealthiest members. Extreme income inequality is a key financing mechanism for the profligate and lavish lifestyles of the wealthiest members of society, lifestyles which are highly resource- and carbon-intensive. An Oxfam study found that the richest 10% of people on the planet produce half of all individual consumption-based fossil fuel emissions, while the poorest 50% are responsible for only around 10% of emissions.

The carbon footprint of the world’s richest 10% can be as much as 60 times higher than that of the poorest 10%. Widening income inequality only exacerbates this issue, because all the lost income for poorer groups is funneled into the pockets of the world’s biggest individual polluters and spenders.

Certainly, wealthy households with large amounts of disposable income may have a higher propensity to save money than poorer households, which could reduce total demand in an economy and consequently reduce consumption. Poorer households spend much larger portions of their income, simply because they need to cover basic expenses, but while wealthier households might be able to save larger portions of their incomes, the sheer amount they spend tends to offset any drop in demand and consumption. There have been several studies that show how increases in income inequality in an economy do not have any real effect on reducing consumption once averaged.

Why Do We Buy?

But even if income inequality were to lead to reduced consumption, it would not be enough to mask a key behavioural trend of consumption. People, regardless of their income, spend money for several reasons, including to meet basic needs and to experience more comforts. But behavioural economics tells us that people can often also spend money for another reason: social certification and self-respect.

The influential sociologist and economist Thorstein Veblen coined the term ‘conspicuous consumption’ in 1899, to describe a particular trend he had noticed in why people spend money. Veblen believed that people publicly and conspicuously spend money on luxury and often unnecessary goods and services in order to put the economic power of their income or wealth on display. To these consumers, the act of spending more money and buying more things is how they reach or maintain a certain social status.

Because it is relatively difficult to quantify, the pursuit of status is an economic factor that is easy to leave aside in any study on why consumers behave the way they do. But it is important, perhaps even crucial, in guiding the actions of individuals. American political and moral philosopher John Rawls called self-respect “the most important primary good,” and in his seminal work, The Great Transformation, Hungarian-American political economist Karl Polanyi noted how an individual will be motivated above all else by an interest in “safeguarding his social standing, his social goods and his social assets.”

If the search for social status and self-respect is so critical to driving higher rates of consumption, then rising income inequality can only exacerbate materialistic consumption within a society. Veblen’s theory of consumer behaviour has been used to examine how inequality can encourage households to increase their consumption in a quest for higher prestige and social certification. In societies with extreme inequality, a majority of people are stuck in low income traps, yet still believe that upward social mobility is possible, and the key to achieving this upward mobility is to increase one’s consumption and materialistic behaviour.

This is a problem, since the environmental crisis has been exacerbated in no small way by growing materialism within societies. This 2014 study, focusing on the US, found a correlation between rising income inequality and a society’s carbon footprint, concluding that extreme income gaps between the wealthy and the poor place pressure on the latter to grow their social status primarily through increased material consumption.

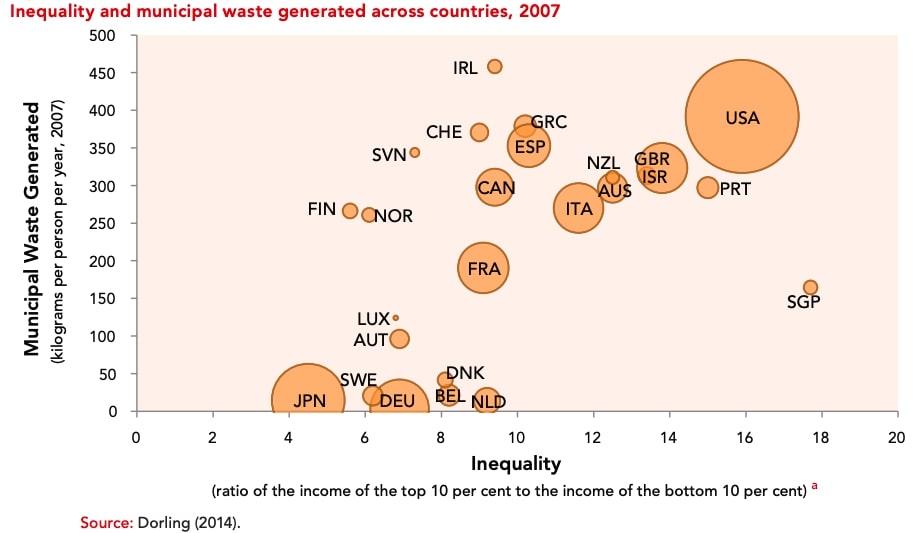

This is not only a matter of wealthy countries perpetuating more environmental harm. Affluent countries with low rates of income inequality, such as South Korea, Japan, France, Italy and Germany generally pollute much less than affluent countries with higher inequality, such as the US. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs released a detailed report in 2015, which compared differences in biodiversity loss, food and waste consumption and waste generation between countries with high and low inequality. The report determined there to be a correlation linking rising inequality in a country to worsening outcomes on environmental and sustainability standards.The authors recommended reducing inequality as an important mechanism to protecting natural habitats.

Figure 2: Ratio of inequality and amount of municipal solid waste generated in select countries. Circle size refers to the country’s population size; United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs; 2015.

It is exactly because of the conditions of emotional insecurity that accompany extreme inequality that people in unequal countries are driven to consume more and buy more items they do not need only to quickly throw them away in a vicious circle, often with a goal of social validation in mind. A strong example of this is fashion, as shown in this 2015 survey of UK women. The survey found that most new clothes are only worn three to seven times before being discarded, mainly out of a fear of appearing to wear the same clothes twice on social media. The same is true of carbon-intensive heavy meat consumption, which is more prevalent in unequal countries.

The evidence points to a simple fact: in countries with high inequality, the wealthy are able to spend and consume indiscriminately, while for individuals with lower incomes, the pressure to buy items to keep up with peers, with the trendsetters, is enormous. This is true for luxury goods and status symbols like clothes and cars, but also for the resources we need to survive, such as food and water.

Inequality exacerbates these consumer behaviours. Even if we as individuals are encouraged to better ourselves, we are made to do so within a world defined by advertising and constant consumption. The definition of success in this world is more dependent on whether or not we have achieved a certain social status, not on whether we are living in a sustainable and equitable society.

Raising Standards For All

Fixing income inequality will not immediately fix these consequences of consumer capitalism, but if we can change these definitions of success, it would be a start. Extreme inequality is simply untenable; the social and economic consequences of inequality are well known, and the growing body of research on inequality’s environmental impacts represent yet another reason for policymakers to tackle this serious problem.

So why haven’t they? The answer is rooted in how power is distributed in affluent societies. The wealthy stratas of society, occupied by political and business elites, obviously benefit from profiting more while the poor receive less, but also stand to gain much more from looser controls on environmental degradation than lower income groups, because fewer rules make their higher consumption cheaper, and allow their assets to generate more wealth.

If the problem is how power is distributed, then any solution has to involve policy mechanisms that allow power to be dispersed more equitably. Comfortingly, none of these remedies are new or groundbreaking, only politically unappealing. To reduce inequality, a limit must be placed on extreme wealth. The lifestyles of billionaires, and the inequality that inevitably accompanies the permittance of extreme wealth, are simply incompatible with an ecologically sustainable and socially dignified world. To save us from the twin crises of environmental disaster and socio-economic despair, extreme inequality cannot exist. This obviously means erasing extreme poverty, but it also means eradicating extreme wealth.

The prominent and popular French economist Thomas Piketty is undoubtedly of this view, as he has called for billionaires to simply be taxed out of existence. This can be done through progressive tax schemes that increase relative to the taxpayer’s wealth. Similar plans have been put forward in the US by the Democratic Party’s more progressive wing, notably championed by US Senator Bernie Sanders. Other proposals include raising the minimum wage, creating a maximum wage and implementing global wealth taxes targeted at multinational corporations.

The ultimate goal, however, is to transfer more power from the employers to the employees. In many affluent countries, workers have little bargaining power in labour markets, and as a result employers have been able to keep wages at historically low levels. Granting workers more rights, protections in the event of unemployment and the opportunity to unionise can give employees more agency over which wages to accept, and which they can reject.

But even in a world without extreme inequality, people from all walks of life will still be searching for self-certification and better self-esteem somehow, so would excess consumption still be a problem?

While reducing inequality would eliminate some of the pressures that drive us to consume so much, buying things is not the only way to self-validate ourselves. Improving environmental quality, reducing inequality and fostering better civic engagement can all lead to a happier and more prosperous society. Buying new things and consumption in and of itself are not necessarily bad, especially for people in poorer countries who are in need of the fruits of technological and material progress, but a focus on consumption as the primary measure of success and self-validation reduces the potential for people to certify the value of their lives through these more sustainable metrics.

These innate tendencies of consumers are only exacerbated by extreme instances of inequality, an emblem of capitalism’s dysfunction that is spreading across the world’s wealthiest countries. Our basic resources and our environment is suffering more because of it, but people are suffering as well. Extreme inequality is a negative and debilitating consequence of consumer capitalism, and invariably causes suboptimal use of human resources and widespread hardship.

Increasing needless consumption and placing more power in the hands of the wealthy impedes society’s ability to face our greatest challenges, and this needs to be fixed. To safeguard our environment and the dignity of each human being, a reorganisation of our institutions and systems of self-validation is required. We need to redirect the energies we expend in seeking fleeting social certification of our value toward non-material goals, such as having more rewarding professions, more collective communities and a healthy environment. This is certainly a long-term goal, but reducing inequality and eliminating extreme wealth are important first steps.

Featured image by: Flickr