COP26 is in the books, and the way the summit wrapped up has attracted as much condemnation as praise. But regardless of how the climate conference ended, the talks were an instrumental part of an ongoing and complicated process that does move the needle forward. We can be disappointed by COP26, but it is crucial for everyone to remember that it is only a small part of a process that is far from over.

—

It is easy to feel short-changed by the way COP26 turned out. After last-minute objections by major emitters, the Glasgow Climate Pact ended up being considerably watered-down and small but important language was revised. And despite a slew of new commitments, pledges and targets, it is still hard not to be skeptical that these will actually be respected.

But whether COP26 should be considered a success or not, saying that no progress was made is a difficult argument to back up. There are several positive takeaways from this year’s edition of COP, and while many were hoping for more, we are undoubtedly in a better position now than before the summit took place.

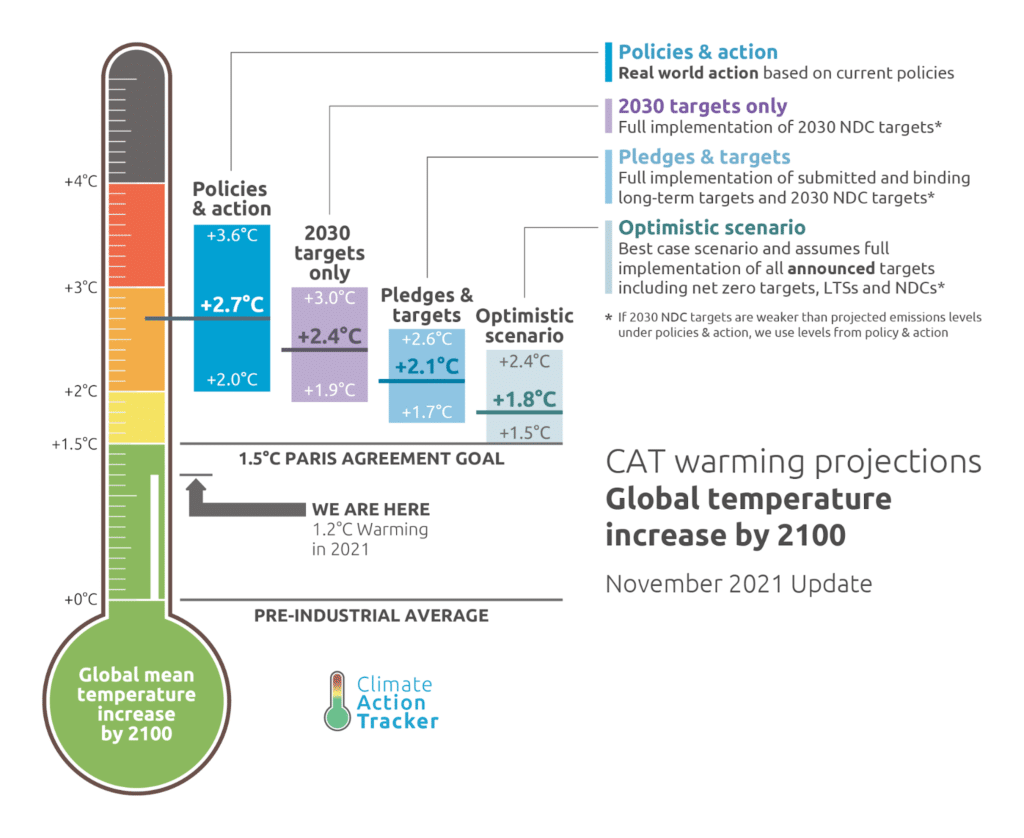

Temperature rise projections have also been adjusted, and now indicate that we are on track for 2.7C of warming, and as low as 1.8C depending on how aggressively we reach to meet our targets. This is still way higher than our definitive goal to keep temperature rise below 1.5C, but is far better than the 4 to 6C rise we were on track for a decade ago.

It may be hard to believe, but the COP26 climate conference more or less did its job. Could it have done more? Probably yes. Was COP26 supposed to provide the entire world with a trajectory to keep temperature rise below 1.5C? No, but we should never have expected that.

It is important to remember what COP represents in our global efforts to tackle climate change. The UN’s annual conference of parties, usually referred to with its acronym as COP, brings 197 countries together to talk, share accomplishments and encourage one another to raise targets. COP is an exercise in international compromise, and it is impossible to reach a compromise without someone being disappointed.

There are several ways to put COP’s role into a greater context that can not only make us feel better about Glasgow’s outcome, but also more confident about the process’s future. The bottom line is that COP is all about incremental progress and moving the needle forward. COP26 was largely successful in this, but the work is far from over.

Building on the Paris Agreement

At COP26, and probably at every other COP for the foreseeable future, delegates are not expected to come up with a new overarching goal. We already have it: keep temperature rise well below 2C above pre-industrial levels, and pursue best efforts to remain below 1.5C.

This goal was established six years ago, at COP21 in Paris. This is our target if we want to protect the world’s most vulnerable regions from the devastating effects of accelerated climate disruption, and the cascading feedback loops that will impact the entire world if temperatures continue to rise.

From here on out, every COP climate conference is supposed to be putting more meat and substance on the framework established in Paris. Delegates are supposed to gather, present what their country is doing to meet the Paris goals and pressure laggards into doing more. All this comes together when agreements are drafted and incorporated into the framework Paris gave us.

The additions that the Glasgow Climate Pact made to the Paris Agreement are a definite improvement. For a number of unknowable reasons, the term ‘fossil fuels’ was never included into the text of the Paris Agreement, despite their being the single largest contributor to global warming. And while the last-minute change to ‘phase-down’ coal instead of ‘phase-out’ was certainly discouraging, this was the very first time that fossil fuels have been specifically mentioned in a COP document, in this case coal.

So if the goal of the Glasgow Climate Pact was to flesh out the Paris Agreement in more concrete terms, then it was more or less successful. After six years of deliberations, we now have an idea of what the global carbon market first proposed in Paris will look like. What was once an abstract proposal is now a tangible set of rules for countries to follow. This could unlock trillions of dollars in tradable carbon credits that will incentivise innovations in carbon capture and storage technology, as well as finance adaptation efforts in the developing world.

Glasgow’s global methane treaty, anti-deforestation pledge and independent pacts to phase out fossil fuels all build on the foundations of Paris, and that is largely what a climate conference is for. It is a forum where these agreements can be hashed out, but the actual policies to make these targets a reality were never going to be announced, much less enacted, in Glasgow.

COP’s Role To Play

COP is organised by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), but as a transnational entity, the UNFCCC does not really have the power to do much of anything. That power remains pretty much exclusively with nations, subnational governments and the private sector. As a body, the UNFCCC convenes representatives and creates a structure that publicises national goals.

This was always going to be the purpose of COP. The UNFCCC realised early on in its history that it did not have much power to actually make change happen, and the best it could do was make it as easy and compelling as possible for nations to individually put their best efforts into mitigating climate change.

Take the global methane pledge for instance, to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030. This doesn’t mean that every signatory country has to reduce their methane emissions by 30%, but they have to enact domestic targets that are in line with a global 30% reduction goal.

The pace at which Australia phases out its methane emissions won’t be determined by what its diplomat said in Glasgow. It will depend on local politics and trends in Australia, what makes economic sense and what the political priorities are. Because this is a global, multilateral goal, there is no explicit requirement or enforcement mechanism for individual countries to take any action to a specfic degree. That comes later, but COP plays no part in the domestic politics that actually see these goals realised.

The UNFCCC and COP are an important part of the process, but neither is the ultimate cure to the climate crisis. COP’s value is that it takes a snapshot of every country in the world, and of how they’re doing. Rich and poor, developed and developing, fossil fuel-dependent and transitioning. Everyone has a seat, and everyone is measured up against one another.

The utility of this process is that it provides transparency and peer pressure, which can be effective in moving governments towards action. COP relies on incremental progress: gradually shifting baselines, making more ambitious policies progressively normalised and bringing more actors to the table.

Unilateral Responses to COP

But incremental progress can only take us so far when the window of opportunity we have to mitigate climate change is so small. COP is a multilateral process, and like all multilateral processes, it requires compromise, extensive deliberations and outcomes that are rarely ideal for everyone involved. While multilateralism can certainly be useful, unilateral policies have a role to play as well.

The EU’s proposed carbon border adjustment tax is a perfect example. The scheme, slated to kick off its transitional phase in 2023, will impose levies on imports into the EU that are particularly emission-intensive. A carbon border tax is a departure from most carbon pricing models, which tend to only affect domestic industry, and instead targets the ways other countries and companies operating abroad do their business. The EU, an entity with relatively ambitious climate policies and among the most credible contenders to the title of global climate leader, can impose this tax to ensure that other countries are complying with international emissions standards.

Measures such as a carbon border tax are decidedly anti-COP, in that they are less diplomatic and represent more forceful action from major actors to incentivise other countries to ramp up their ambitions, but we will probably be seeing much more of these kinds of policies in the future.

The world as a whole is trending away from fossil fuels. The commitments made by the private sector at the COP26 climate conference, including a pledge to mobilise over USD$100 trillion to finance the global energy transition, put independent and private actors in the driving seat. Philanthropists and other private funders also came through with big promises to ramp up their financing efforts. What this shows is that there is a whole lot of willpower to make things happen, and governments and multilateral fora do not have to be an obstacle to that.

National governments are important, but smaller entities also play a big role, arguably bigger. City and state-level governments have a tremendous impact setting local environmental policies that may not make international headlines, but are nonetheless critical, given that cities account for up to 76% of the world’s energy-related CO2 emissions. Local governments can independently decide to make their cities greener, commission more renewable energy projects, expand public transportation initiatives and retrofit aging infrastructure that contributes to inefficient energy use. These are not policies that happen because of COP, they happen independently of it.

What national governments do is very important, but it is not even close to the whole story. So when we see diplomats make half-hearted commitments at summits like COP, we need to keep in mind that there is so much more progress happening that we can’t even see. Climate truly is everything, it involves every corner of our governments and our economies, but what that also means is that many of our responses to climate change are invisible, and certainly not on display at COP.

High expectations and high disappointment is in the nature of events like the COP climate conference, but we need to remember what COP is really about. It is a spotlight on a world that is – slowly but with growing expediency – moving towards progress in the midst of an epic and existential challenge.

We cannot be complacent, as there is still so much work to be done, but the needle is inching forward in ways that we cannot always see. COP has its value, but it is far from the only thing we have going for us, and unilateral and independent action is just as, if not more important.