Since its launch in 2007, the Great Green Wall (GGW) – the ambitious plan to plant millions of trees across the Sahel Region in Africa to fight desertification – has almost reached a standstill. Some progress and achievements were made in the past decade. However, the initial goals of the initiative are far from being reached. In an effort to save what many see as an “ambitious but possible” and “certainly necessary” plan, in January 2021 French President Emmanuel Macron announced the ‘Great Green Wall Accelerator’, a massive economic boost over the next five years. These economic incentives – he said – should lead to the completion of the Wall by 2030.

—

With the rapid advancement of science and environmental technology, new innovative ideas on how to reverse the dangerous paths that the world’s ecosystems and natural habitats are taking arise continuously. To reduce the process of desertification impacting the Sahel Region, the African Union (AU) announced in 2007 the so-called Great Green Wall Initiative, a plan to plant a broad continuous band of trees covering 8,000km of land “across the entire width of the Continent”, from Senegal in West Africa to the Eastern Republic of Djibouti.

Funded by the European Union, the World Bank, and the United Nations, the main goal of this megaproject was to rescue the Sahel, one of the most vulnerable regions globally to climate change, where almost 50% of the total land has been constantly degrading due to practices of overgrazing, deforestation, and persistent droughts. These dangerous practices have constantly increased due to the rapid growth of the population of the region, which is expected to reach 340 million by 2050. By planting trees across the Sahel, the hope was to reduce desertification by moderating temperatures, wind patterns, and soil erosion as well as increasing humidity for agriculture, as O’Connor and Ford explain in their 2014 paper on the effectiveness of the Wall. It sounded like an ambitious plan, but it was seen as something that could potentially work and reverse the patterns of climate change.

The implementation of the Wall, however, has struggled to make headway. Indeed, while the original goal was to restore 100 million hectares of land by 2030, a UN Status Report published last year announced that only 4% of the target has been achieved in more than a decade since the initiative’s launch. What has contributed to what many have described as a failure of this ambitious project – that was developed to improve livelihood, create jobs, and fight back the consequences of climate change – are on the one side the lack of funding and technical support, on the other side the poor monitoring of the progress made. Of the 11 African countries directly involved, several were lagging way behind their targets at the time of the report’s publication. There is no doubt that some positive changes were achieved, such as the creation of 350,000 new jobs and around USD $90 million in revenue generated since its launch. However, the over USD $200 million invested since 2007 should have contributed to much more significant and transformative achievements.

You might also like: ‘Great Green Wall’ in Africa Just 4% Complete, Halfway Through Schedule

A collective acknowledgment of the failure in hitting the initiative’s original goals by several world leaders has led to the decision to massively increase the funding destined to the Great Green Wall, a project in which they still strongly believe. For this reason, in January 2021 at the One Planet Summit, President of France Emmanuel Macron announced the ‘Great Green Wall Accelerator’. On this occasion, leaders of 134 countries, the World Bank, and the United Nations came together to discuss the implementation of international climate agreements by supporting several local projects. One of them is the GGW. For this initiative, they pledged to provide nearly USD $14 billion in funding over the next five years from a coalition of international development banks and governments, with the main objective to accelerate its completion by 2030 and so be able to help small farmers – which in the Sahel account for almost 80% of the population – as well as support agribusinesses and create green jobs.

With greater access to economic resources, all African countries involved in the project – many of which have not received enough financial support to implement the initiative – will now be able to “access the necessary funds” according to Mohamed Cheikh El-Ghazouani, President of Mauritania and current chair of the Conference of Heads of State and Government of the Pan-African Agency of the Great Green Wall. For him, the COVID-19 pandemic has also played a major role in bringing about this Accelerator, as government and international organisation leaders and financial institutions around the world realised the imminent threat of climate change and understood the necessity to adopt smart policies and invest in green projects to counter its devastating effects, revive economies and thus ensure a sustainable pandemic recovery and a social transformation.

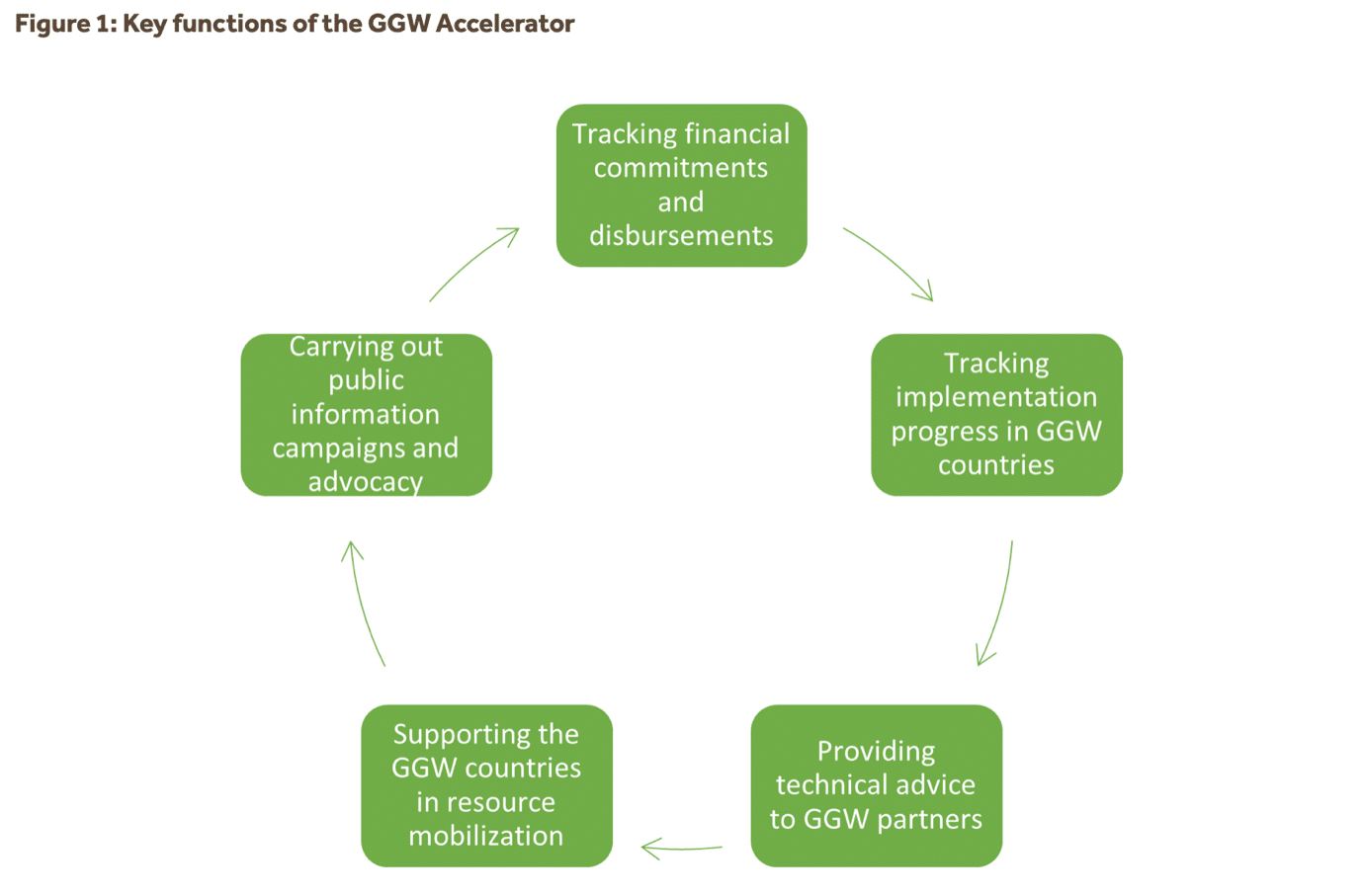

Key functions of the GGW Accelerator. Image: Great Green Wall (2021).

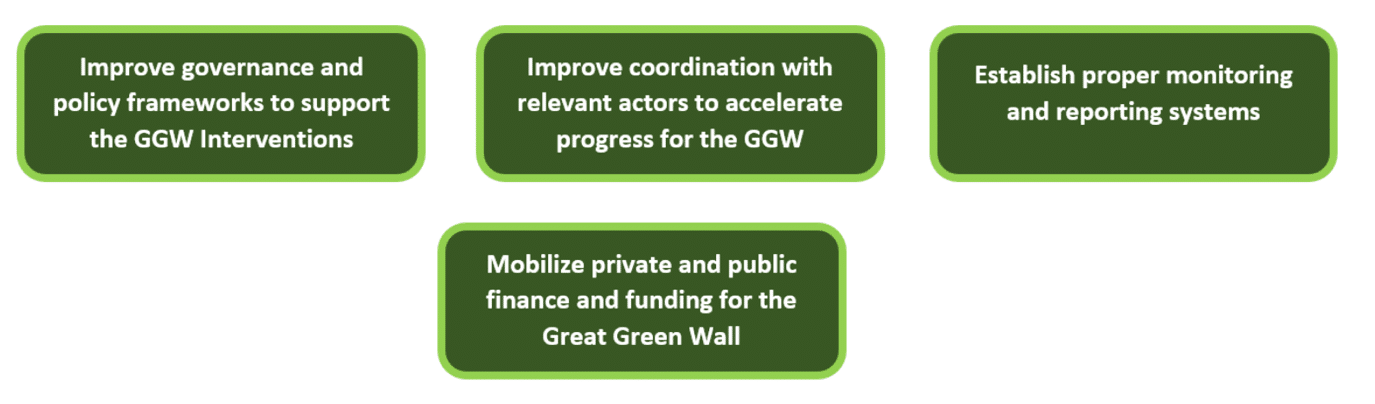

Such ambitious commitments will be brought about not only through the mobilisation of more funding for the Wall but also with interventions on governance and coordination. The latter has been recognised – along with economic motifs – as major reasons for the slow implementation and partial failure of the plan. For this reason, leaders and organisations supporting this massive economic boost announced plans to improve governance and policy frameworks as well as coordination with relevant actors to enable GGW interventions. Furthermore, the intention is to establish a proper monitoring and reporting system that will accelerate progress for the Great Green Wall.

Key adjustments in the implementation of the GGW Initiative. Image: Great Green Wall (2021).

This revisited approach has been welcomed by those who recognised that the problems that have hindered the advancement of the Wall were not exclusively economic in nature. As the coordinator of the Great Green Wall Initiative for the African Union Commission Elvis Paul Tangem rightly noted: “You can plant a tree for $1, but you cannot grow a tree for $1”. At the same time, however, forestry projects usually fail also because they cannot properly address fundamental social and ecological concerns as well as questions of feasibility. As easy as it might sound, planting a tree – especially if in extreme weather conditions such as those of the Sahel region – requires knowledge and constant care. For them to survive, it is crucial to reflect on which types of trees should be planted in the first place, as well as to investigate which kind of species the local communities would benefit from.

All these factors have not seriously been taken into account since the project’s launch and it is believed that, without the direct involvement of the indigenous population, the project cannot be successfully implemented. As a matter of fact, the lack of community input is believed to be one of the leading causes of the failure of such projects. Newly planted trees cannot be neglected, and it is important to ensure that these communities have the necessary resources to water and protect them as well as keep the soil fertilised.

Even though it may sound simply like another attempt to implement an ambitious project that has already failed once, the changes in the approach that the government and institutions involved are planning to take sound reassuring. The new goals of restoring 100 million hectares of land, sequestering 250 million tons of carbon, and creating millions of jobs in rural areas across the Sahel are now set to be achieved during the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration, which will end in 2030. For the new plan to work, it is crucial to learn from past mistakes. This means implementing the plan by paying attention to not only economic but also ecological and social issues. This means allocate adequate funds, listen to the needs of the local communities, actively involve them and provide them with the necessary resources to make sure that they can guarantee the long-term success of the project.

Featured image by: CIAT via Flickr

You might also like: What is the ‘Great Green Wall’ of China?