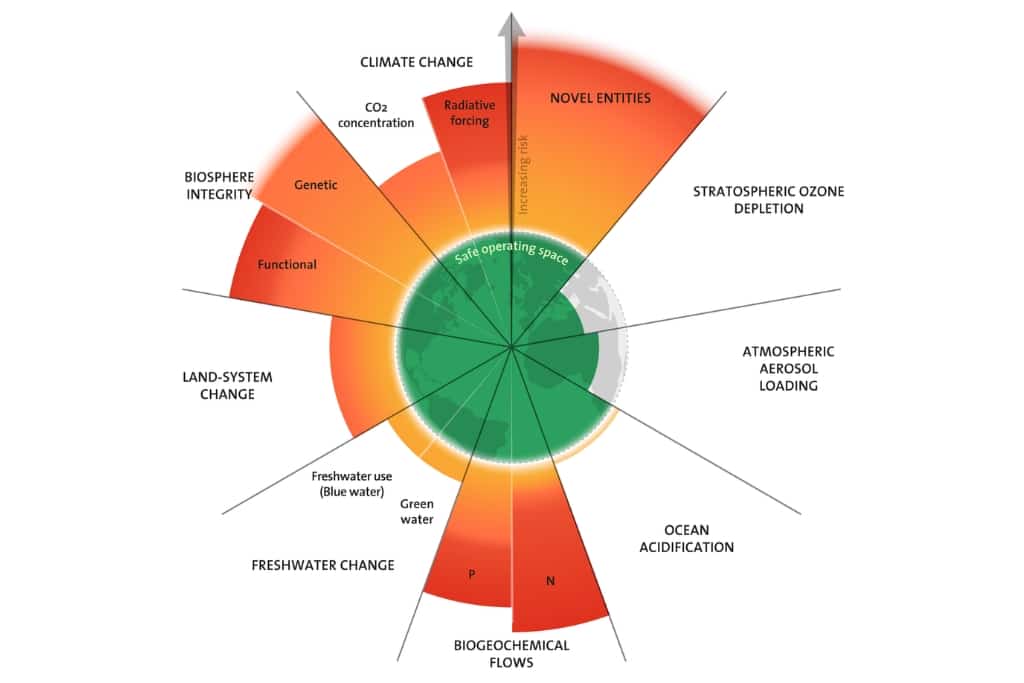

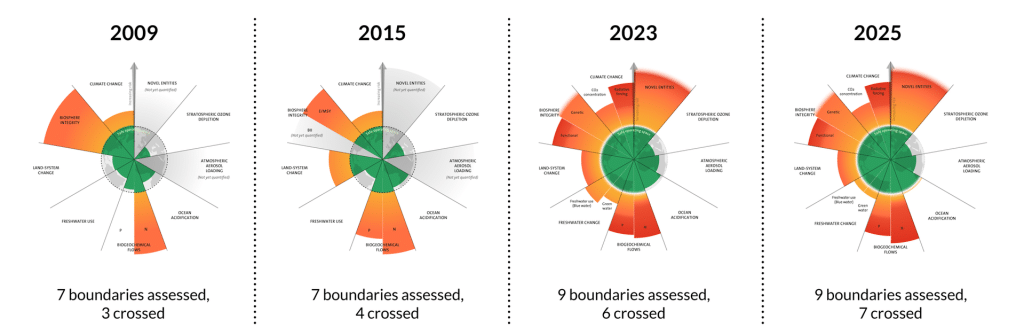

We have now crossed seven out of nine planetary boundaries: climate change, biosphere integrity, novel entities, land system change, freshwater use, biogeochemical flow and, most recently, ocean acidification.

—

Last month, humanity crossed another planetary boundary: ocean acidification.

A new report from the Planetary Boundaries Science Lab at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) revealed that we have crossed a seventh planetary boundary, out of the nine that have been identified as critical for our current Earth System.

The Earth System as we know it has been relatively stable for 11,700 years – the duration of the Holocene epoch, the current geological period of Earth’s history. This is the only state of the Earth that we know for certain can support human societies as we have designed them.

But human activities, such as fossil fuel burning, deforestation and intensive agriculture, have affected the Earth System to such an extent that we have irrevocably changed it. The most known example is climate change, but we have also impacted land systems, biodiversity, and the ocean, among other factors.

The nine planetary boundaries were first proposed by a group of 28 scientists led by Johan Rockström and Will Steffen. They constitute a safe operating space for human beings. Crossing them translates into severe harm to human wellbeing and the planet as a whole. If we continue down a path leading us further away from the Holocene, we are very likely heading towards a very different state of the Earth System. Already, researchers state we are likely living through the sixth mass extinction, for the first time driven by human impacts. In the past 50 years, wildlife populations have fallen by an estimated 73%.

More on the topic: Toward a New Global Approach to Safeguard Planet Earth: An Interview With Johan Rockström

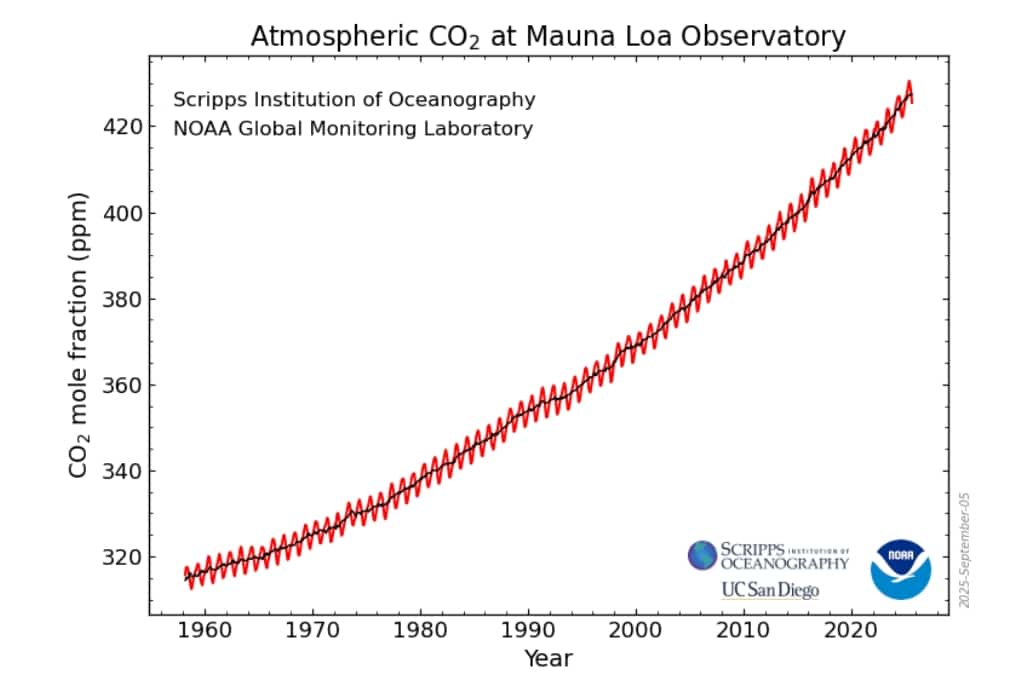

We have now crossed seven out of nine planetary boundaries: climate change, biosphere integrity, novel entities, land system change, freshwater use, biogeochemical flow and, most recently, ocean acidification. For example, the planetary boundary set for climate change is proposed in the form of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration of 350 parts per million (ppm). This is an important metric because of its long life in the atmosphere and the large amount of CO2 that humans are continuing to emit.

We currently stand at 425 ppm of CO2.

Ocean Acidification

No part of the ocean is untouched by the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution, according to a report by the European Union-funded Copernicus program. Over 10% of marine biodiversity hotspots are acidifying faster than the global average. Sea levels have risen with record-high values in 2024 and are rising at an accelerating rate. Globally, oceans are reaching record high temperatures. Arctic sea ice has reached four all-time record lows between last December and March. The warming ocean is causing the boundaries of marine biophysical provinces to shift toward the poles.

The ocean’s surface pH has fallen by around 0.1 units since the start of the industrial era, a 30-40% increase in acidity. This has pushed countless marine ecosystems beyond safe limits and degraded the oceans’ ability to act as Earth stabilizer. The ocean absorbs a large amount of CO2 that humans emit into the atmosphere – between a third and a half of all of the CO2 humans have released since about 1850.

We depend on the ocean taking in carbon emissions, but too much CO2 absorption affects its acidity level. Since 1850, ocean acidity has increased by 30-40%, according to the report – a rate roughly ten times faster than any time in the last 55 million years.

Ocean acidification poses a direct threat to many marine organisms, such as corals and plankton, that rely on calcification to build their protective shells and rigid skeletons. The increased acidity of seawater reduces the availability of carbonate ions, which are the essential building blocks these organisms need. As a result, they struggle to grow, repair, and survive.

This biological damage ripples through the marine environment because many of these small calcifiers – particularly plankton – form the base of the entire ocean food web. When these foundational species decline, the effects cascade upward. This means that while larger creatures like fish might not be harmed by the acidity itself, their primary food sources are disappearing, threatening the stability of the entire ecosystem and eventually impacting human economic activities like global fisheries, aquaculture, and coastal tourism.

The ocean has absorbed our emissions for centuries, and limits have been crossed. We need to take action to bring back our economies and societies within a safe operating space to preserve life in the ocean and on Earth, starting by lowering our CO2 emissions by transitioning to clean energy sources.

More on the topic: What Is Ocean Acidification?

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us