Today, there are 500 times more microplastics in the world than stars in our galaxy, a clear sign that the plastic pollution epidemic has spun out of control. We are producing, using, and throwing away more plastic than we ever did before and, whether we like it or not, most of it will stay with us forever. Roughly two-thirds of all plastic ever produced remains in the environment today, most of it in the form of microplastics, tiny toxic particles that are polluting the air, soil, and rainwater. These eventually end up in animals and even humans through the food chain. We explore what microplastics are and to what extent they are harmful to the environment.

—

The term ‘microplastics’ was introduced in the mid-2000s to describe tiny particles of plastic up to five millimetres in diameter. However, scientists first found plastic debris in the environment, particularly in our oceans, more than 50 years ago, when mass production of plastic products first began. For a long time, their main concerns over microplastics were revolving around the threat that these tiny, almost invisible particles represent for marine creatures due to entanglement and ingestion. However, we are close to reaching a point of no return in the plastic pollution epidemic. Humans now generate nearly 300 million tonnes of plastic waste every year, 60% of which end up in our natural environment. Experts are becoming increasingly concerned over this issue and prompted new research on the long-lasting damages of microplastics not only to the environment but also to animal and human health.

What Are Microplastics?

Plastics do not break down, but they can degrade in quality and turn into smaller pieces – which we commonly refer to as ‘microplastics’ – through processes such as weathering and exposure to wave action, wind abrasion, and ultraviolet radiation from sunlight. These fragments of plastic are smaller than 5mm and larger than 1 micron (1/1000th of a millimetre) in length, close in size to one sesame seed.

Researchers categorise microplastics into two main types. Most ‘primary microplastics’ are products designed for commercial use that are intentionally manufactured to be small. Some examples include clothing and other textiles, fishing nets as well as microbeads in toothpaste and in personal care products like body scrubs. However, there is a common understanding that the largest part of microplastics dispersed in the environment comes from mismanaged waste that is bigger in size, such as plastic bottles and containers. This is commonly referred to as ‘secondary microplastics’, which include particles resulting from the breakdown of these larger plastic items. The latter type also accounts for the majority of microplastics found in the oceans – approximately 69% to 81% according to estimates from the European Parliament.

Some of the other biggest sources of microplastics include tyres, tennis balls, cigarette butts, tea bags, and synthetic clothing. The latter tops the ranking as the main source of microplastics, accounting for 35% of the total primary microplastic pollution.

Where Can Microplastics Be Found?

According to the United Nations, more than 51 trillion microplastic particles litter the world’s seas, a quantity that outnumbers the stars in our galaxy by 500 times. Since microplastics became a pressing topic among environmental researchers at the beginning of the 21st century, these tiny, toxic particles of plastic have been thoroughly studied. Researchers have found them pretty much everywhere, from inside marine creatures to food and water as well as, not surprisingly, even in humans.

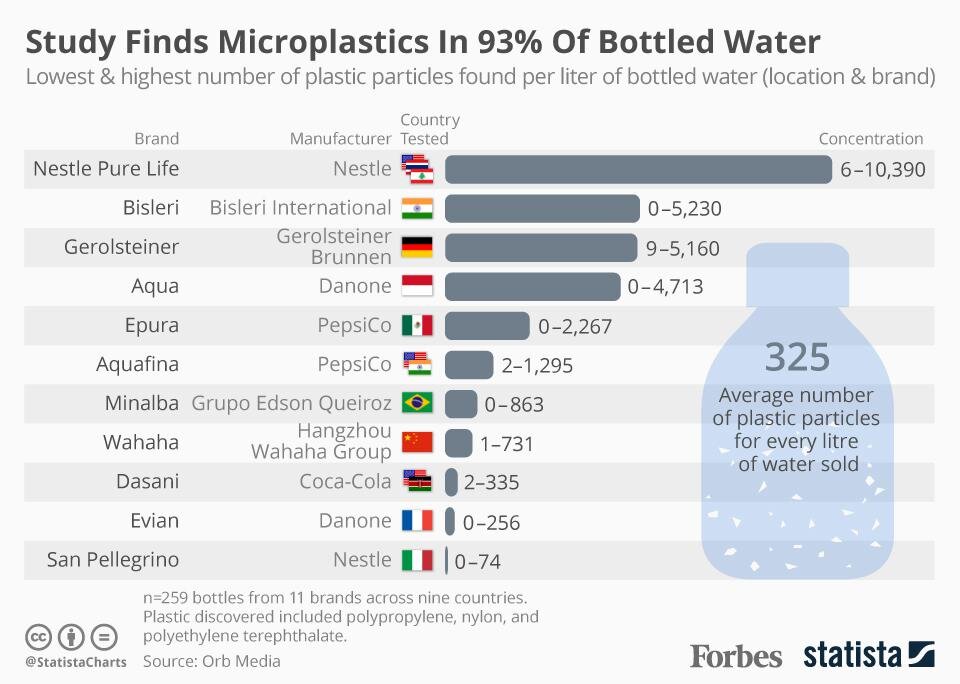

According to Greenpeace, fruit like apples and pears have the highest content of microplastics, with an average of 195,500 and 189,500 particles per gram respectively. Similarly, broccoli and carrots are usually the most contaminated vegetables, averaging more than 100,000 plastic fragments per gram. The water we drink every day is also a huge source of microplastics. A study conducted by the State University of New York in Fredonia found that 93% of bottled water contains microplastics, an average of 325 particles per litre, and 22 times more than tap water.

Oceans are by far the world’s largest dumping ground for plastic, with more than eight million metric tonnes ending up in seas every year and studies that estimate that by 2050, our seas could contain more plastic than fish. Thus, unsurprisingly, sea salt as well as most fishes and shellfishes also contain high amounts of microplastics. Given that these particles are absorbed in an animal’s gut, seafood such as mussels, oysters, prawns, and shrimps usually contain higher levels of microplastic. Around 50% of fish in the Mediterranean Sea and 80% of fish larvae in EU estuaries have ingested some quantity of microplastic.

Through the modern food chain, these toxic substances are also easily transmitted from marine wildlife to humans. Recent studies have found microplastics in human blood, human lungs, and human placenta for the first time, a warning sign that particles from rampant plastic pollution could also be making their way into organs in the body. A 2019 study estimated that an average American citizen ingests between 74,000 and 121,000 plastic particles every year, depending on age and sex.

You might also like: Microplastic Found in Human Blood for the First Time

Are Microplastics Harmful?

While we are increasingly aware of where microplastics can be found, we are still relatively in the dark about their impact on the environment and especially on human health. But there is no doubt that microplastics contain highly toxic and harmful chemicals. Even in the manufacturing phase, plastic is processed with additives such as plasticisers, flame retardants, UV stabilisers, and pigments, which account for nearly 4% of the weight of microplastics. Furthermore, plastic debris accumulating in the ocean absorbs persistent organic pollutants (POPs) from the water which have been found to have critical adverse health effects. Several studies have confirmed how microplastics that are ingested by marine animals make their way up the food chain. However, it is no longer just seafood that poses a threat to humans since microplastics make their way into all kinds of food.

Because this is still a relatively new research field, scientists cannot fully estimate the long-lasting impact of these particles. A recent study exposing the presence of microplastics in the human placenta found that these carry with them substances that can disrupt the regular function of hormones and cause long-term effects on human health such as oxidative stress as well as chronic DNA damage and inflammation. Furthermore, the surface of plastic particles is often colonised by micro-organisms, some of which have been identified as human pathogens. A 2016 research identified one of these pathogens on microplastics sampled from the North and Baltic Seas and associated with cholera in humans.

Contrarily, effects on marine life have been investigated more widely, with several studies demonstrating how the absorption of plastic particles can cause mass mortality of fish and seabirds. Microplastics contribute massively to the loss of biodiversity and threaten ecosystem balance. A study commissioned by Seas At Risk and carried out by the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology found that fishes who ingest microplastics experience energy depletion, fertility as well as behavioural problems, and, in extreme cases, even premature death.

How Can We Avoid Microplastics?

It is nearly impossible to avoid microplastics altogether, and yet there are effective ways to reduce their spread and the risk of ingesting them. Considering the enormous quantities of plastic particles that some foods and drinks contain, it would be wise to make some swaps, like avoiding bottled water and drinking filtered tap water instead. We can also be more conscious of the clothes we wear and the products we use. Given the high content of microplastics found in synthetic clothes, avoid buying this type of material or be more conscious about the amount of toxic particles that are released every time we wash and dry them. We should also avoid exfoliants and scrubs where possible, as they contain some of the highest quantities of microbeads among beauty products.

You might also like: 10 Scientific Solutions to Plastic Pollution

And yet, as much as individual actions can make a difference, the current trajectory of plastic pollution in recent years cannot be reversed unless governments address it seriously. Countries around the world have banned single-use plastics or are planning to do so, a good first step to reducing overall plastic production. The European Union has set rules on marine litter and was able to achieve a significant reduction in plastic bag usage across several of its Member States through its Plastic Bags Directive. Furthermore, the EU is currently working on policies to effectively reduce overall plastic packaging and making sure that all of it is either reusable or recyclable by 2030. Others have gone further by banning cosmetic microbeads. The Netherlands was the first country to do so in 2014, after calls from the Plastic Soup Foundation to end microbead usage in the production of cosmetics and personal care products, and other nations like Canada followed suit. The textile industry, instead, remains often overlooked despite its massive role in spreading microplastics around the world.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us