Bushfires tearing through southeastern Australia have killed at least 25 people and burnt over 14.8 million acres of land (in comparison, 2.2 million acres of land were burnt during the 2019 Amazon rainforest fires). It is feared that a billion animals have perished, nearly 2000 homes have been burnt down and thousands took to beaches for refuge. The smoke from the Australia bushfires is so dense that glaciers in New Zealand have turned brown from ash and smoke. Adding to the chaos is Australia’s own government, who continue to deny the link between the fires and the climate crisis and intend to use an accounting loophole to reduce its emissions reduction efforts.

—

While Australia bushfires are a regular ecological patterns in the country, this summer’s exceptionally high temperatures and strong winds have spread the fires further into the east coast.

Environmental Factors of the Australia Bushfires

Australia experienced the hottest and driest year in its recorded history in 2019, which was a major contributing factor to the devastating wildfires that continue to rage, the country’s meteorology bureau said.

Dry conditions limit the variety of vegetation cover, which makes areas more vulnerable to fire. Australia’s outback is covered with xeric shrubland and savanna grassland; grass fires can spread as quickly as 14 miles per hour, twice the speed of forest fires.

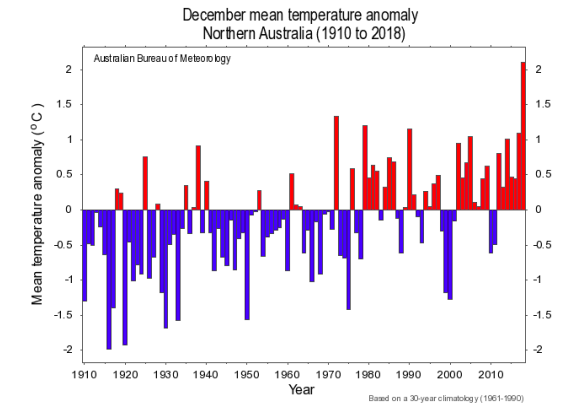

Data released by the climate monitoring body show Australia’s mean temperature in 2019 was 1.52°C higher than average, making it the warmest year since records began in 1910; January 2019 was the warmest month Australia has ever recorded. Rainfall was 40% below average, its lowest level since 1900.

As a result of changing weather patterns in recent years, the fire season has extended by a month in some locations, and fires have become more severe, the bureau said.

The main factor prolonging the summer heatwave is a positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), a climate phenomenon where sea surface temperatures are warmer in the western Indian Ocean and cooler in the east. The cooler eastern Indian Ocean reduces rain in Southeast Asia and Australia, causing droughts and high temperatures inland. Another factor is the unusual Southern Annular Mode (SAM) this summer. SAM is the westerly wind that encircles the southern ocean from west to east. A negative SAM means the westerly wind is unusually north and it creates an anticyclone, driving wind from the inland to the east, fanning the fire to more densely populated areas on the coast.

Once bushfires start, they create their own weather patterns. Hot smoke rises into the atmosphere and forms pyrocumulonimbus clouds, which can cause thunderstorms and ‘dry lightning’ (lightning without rain).

The relatively flat terrain in Australia is conducive to the development of pyrocumulonimbus clouds and contributes to the quick spread of fires.

The burning forests not only add to carbon emissions, but they also remove carbon sinks which will take decades to grow back; 350 million metric tons of CO2 have been released from the fires since September.

Human Factors: People Started the Australian Fires?

According to the Australian Institute of Criminology, more bushfires are started by people than natural causes; fires were deliberately lit around Queensland in December 2019, destroying dozens of homes and forcing hundreds to flee. Fires that become uncontrollable bushfires are mostly in rural areas where there is plenty of fuel available such as grass and bushes.

Bushfires tend to occur when fuel loads in eucalyptus forests have dried out, usually following periods of low rainfall; however, fuels can be managed to prevent fires.

The National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) of Australia carries out hazard reduction in high-risk areas in Australia through prescribed burning of trees and grasses close to developments. This includes fuel breaks, also known as fire breaks, where trees are cleared to prevent the spread of a fire. This is also done routinely around power lines.

Indigenous Australians have been traditionally managing the land for 50 000 years using prescribed burning. By knowing what areas to burn, when and how, areas of expansive grassland on good soils were created and the subsequent variety of trees and grassland meant that the highly combustible eucalyptus forests were unlikely to create intense bushfires.

However colonisation meant that this land management gave way as fire was feared rather than used as a way to manage the lands, resulting in grass plains becoming thick scrub and bushland that is prone to bushfires.

Cuts in firefighters?

Claims from the The Public Service Association that the NSW government had ‘cut fire-trained positions in national parks by 35%’ have been disproved, however there are less rangers than in 2011- down to 201 from 261.

There are 1 044 national parks and wildlife service staff qualified to fight fires, down from 1 349 in 2013 (however environment minister Matthew Kean says that this number included trained firefighters as well as incident response teams with other skills, making it an inappropriate comparison).

The number of firefighters in the NSW Rural Fire Service appears to be static– the number of salaried staff has remained roughly the same as in 2011. However, the firefighting force in national parks is less highly qualified than a few years ago, and there are fewer rangers and more field officers.

The Fire Brigade Employees’ Union says that maintaining the current number of firefighters will not be enough. Hotter and drier conditions, and the rising number of days on which there are higher fire danger ratings, have reduced the time in which agencies can carry out prescribed burning.

Conditions in winter or early spring, when hazard-reduction burning is usually carried out, are becoming less favourable for safely lighting fires. Other factors hindering this planned burning are: the challenges of administering fire management programs across different areas, legal liability considerations and risks to crews and communities.

As the climate crisis worsens and the bushfire season is expected to continue to extend, the amount spent on both equipment and personnel needs to be expanded and increased.

Government response

The blazes have sparked a debate in Australia over whether man-made climate change is to blame. Prime Minister Scott Morrison and his government have been accused of downplaying the severity of the fires and the role played by climate change, and prioritising the interest of the country’s coal industry.

The government is standing firm on its position that there is no direct link between the climate crisis and the Australia bushfires despite public anger and warnings from scientists.

Stepping up efforts to cut emissions would harm the economy, the government argues, especially if it hurts Australia’s exports of coal and gas.

“In most countries it isn’t acceptable to pursue emission reduction policies that add substantially to the cost of living, destroy jobs, reduce incomes and impede growth,” Angus Taylor, Australian Energy Minister, said, without detailing exactly how cutting emissions would raise the cost of living.

The catastrophic fires come as Morisson’s government last year stated its plans to use a carbon accounting loophole from the Kyoto Protocol agreement to fulfil its Paris commitments, saying that the trick would limit the pressure the agreement would place on Australia’s coal and gas exporting industries.

This has angered the international community; Costa Rica Minister of Environment and Energy Carlos Manuel Rodríguez called out Australia, Brazil and the US by name during a press conference. He asserted that proposals like Australia’s to use old allowances towards a new pledge would threaten the integrity of the agreement and put the 1.5°C goal further out of reach.

However, Morrison and his government insist that Australia has the absolute right as a sovereign state to design its nationally determined contribution (NDC) to Paris as it sees fits and he rejects claims that it’s unambitious.

“Australia is meeting and beating our emissions reduction targets,” he told reporters when asked about the climate talks at a press conference in December.

However, a ranking of 61 major economies last month shows Australia has the least protective climate policies; Australia is the world’s largest exporter of coal briquettes, exporting 7% of the world’s fossil fuel CO2 potential. The country releases 1.3% of the world’s greenhouse gases, while its population accounts for 0.3% of the planet’s inhabitants.

Under the Paris Agreement, Australia has committed to reduce its emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2030; it is currently on track for a 7% reduction. The country is considering whether to count what it portrays as ‘overachievement’ over the first and second Kyoto commitment periods (2008-2012 and 2013-2020 respectively) toward its NDC for 2030 under the Paris Agreement.

However, this technical ‘overachievement’ comes from the fact that Australia had substantial domestic deforestation emissions in 1990, which artificially raised its baseline 24% above an average year. Additionally, Australia allowed itself an 8% increase in its emissions in the first Kyoto commitment period compared to 1990 and a 0.5% reduction for the second; Australia is now claiming ‘overachieving’ after choosing less ambitious targets than other countries.

If Australia succeeds in using these carryover credits, it would reduce the country’s 2030 reduction target from 26% to 13.9% below 2005 emission levels using 2019 projections. It’s unclear how the emissions from the current spate of fires will fit into this accounting.

This loophole isn’t popular, but it’s unclear how it can be stopped. However, while there are no legal ramifications for underperforming on a Paris commitment, a report says that there is currently no legal basis for the ‘carryover’ of pre-2021 units from the Kyoto Protocol for use under the Paris Agreement, as they are separate treaties.

Public Opinion

According to a 2019 Lowy Institute poll, 64% of Australians have identified climate change as the most critical threat to Australia’s ‘vital interests’.

The poll indicates significant demographic differences between Australians. While younger Australians are deeply concerned about climate change and its implications, older Australians are less so. 76% of Australians aged 18-44 agreed that ‘climate change is a serious and pressing problem and we should begin taking steps now even if this involves significant costs’. In contrast, 49% of those over 45 agreed with this statement.

Besides bushfires, other extreme weather events that occurred in Australia in 2019 include unusually late tropical cyclones in May, severe storms, large areas of flooding and widespread droughts.

The Garnaut Climate Change Review from 2008 warned that as result of climate change, ‘fire seasons will start earlier, end slightly later, and generally be more intense. This effect increases over time, but should be directly observable by 2020’.

Professor Bob Hill, director of the Environment Institute at the University of Adelaide, says that the only long-term solution to worsening Australia bushfires is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. “This is a global catastrophe that has now hit Australia hard. There is no reason to believe that this is an isolated event,” he says.

Jointly written by Deena Robinson and Felix Leung, a postdoctoral researcher and a scientist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Featured image by: Ninian Reid