With the 2023 UN Climate Change Conference or Conference of the Parties (COP28) a few weeks away, it is time to see where the world stands with respect to climate justice. The ever-widening gap between the Global North and Global South is lurking back at the increasing pace of climate change. Should historical injustice be acknowledged in the fight against climate change? The question received great attention at last year’s COP27 in Egypt, which ended with a historic agreement to set up a Loss and Damage Fund. This article seeks to understand the developments undertaken for the Loss and Damage Fund since its establishment last year and what we can expect to happen at the COP28.

—

What Is the Loss and Damage Fund?

The idea for a Loss and Damage Fund (LDF) emerged from a years-long fight for climate justice as a response to the recognition that climate change disproportionately impacts marginalised communities and exacerbates existing social and economic inequalities.

The origins of the movement can be traced back to various historical milestones.

In the wake of the Industrial Revolution in the mid 19th-century, a fierce race among developed countries to acquire natural resources led to the colonisation of many countries in the Global South. Decades of exploitation of natural resources resulted in permanent damage in the form of increasing pollution and global warming.

The push for climate justice gained momentum as communities around the world experienced the devastating impacts of climate change, such as extreme weather events, sea-level rise, and displacement. These impacts were often felt most acutely by vulnerable populations, including Indigenous peoples, low-income communities, and people in the Global South.

The environmental justice movement highlighted the unequal distribution of environmental burdens and called for equitable solutions. Climate justice advocates argue that addressing climate change is not just an environmental issue but also a matter of human rights, social justice, and equity. They emphasise the need for an inclusive and fair transition to a sustainable future that considers the needs and voices of impacted communities.

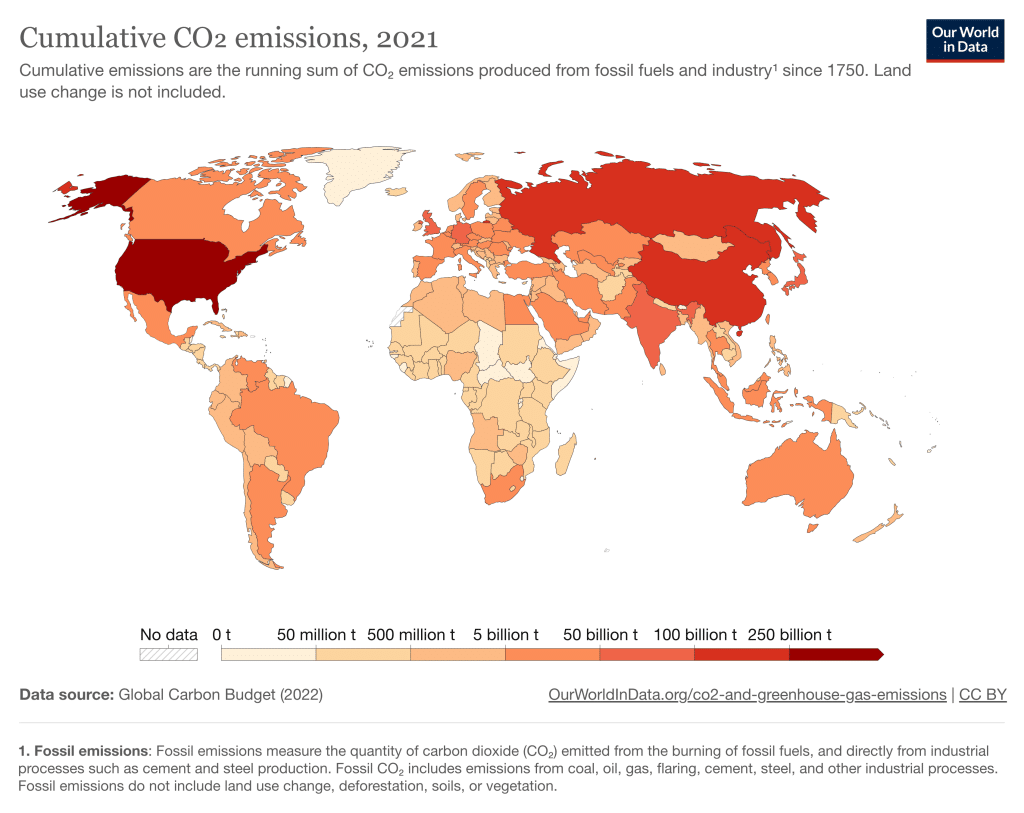

Nowadays, the Group of 20 – or G20, composed of most of the world’s largest economies’ finance ministries, including both industrialised and developing countries, contribute to nearly 80% of global greenhouse emissions.

At last year’s COP27 in Egypt, countries reached an epoch-making deal to establish the Loss and Damage Fund (LDF), which would aim to provide financial assistance to vulnerable developing countries to bolster the social and infrastructural fabric to combat the inevitable impacts of climate change.

The idea of a fund to help developing countries in addressing climate change has been a topic of discussion within the international climate negotiations.

More on the topic: Explainer: What Is ‘Loss and Damage’ Compensation?

While progress has been made in establishing some funding mechanisms, such as the Green Climate Fund, challenges and delays have hindered the full realisation of adequate financial support for developing countries.

At the 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) in 2009, developed countries committed to pay US$100 billion by 2020 to developing countries to finance climate action, though the promise was not kept. It is also worth noting that, according to an Oxfam report, The developed countries have just provided US$83.3 billion of the said commitment, the net financial value of the funds have also been overstated.

The Fund established at COP27 is built on the Common But Differentiated Responsibility Principle (CBDR), a principle under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) which states that countries have different capabilities and different responsibilities in addressing climate change. The question of how the funding will be managed remains largely unanswered to this day. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), developing countries would need ten times more financial assistance to adapt to climate change – estimated at approximately US$300 billion per year by 2030.

Another important step taken at the COP27 was establishment of an advisory board for the Santiago Network, which was formed at the 2019 UN Conference of the Parties (COP25) in Madrid with an aim to provide technical assistance to minimise, avert, and address loss and damage in developing countries. The term refers to the economic, social, and cultural losses and damages caused by anthropogenic climate change to natural and human systems, including human-induced extreme weather events and slow onset events such as sea level rise, rising temperatures, ocean acidification, glacial melting, ecosystem degradation, and desertification. The assistance would facilitate access to research and efficient strategies and dissemination of information.

More on the topic: Explainer: What Is ‘Loss and Damage’ Compensation?

One Year Later: How Much Progress Has Been Made Since COP27?

The Loss and Damage Fund is considered a breakthrough in the history of mankind’s fight against climate change,though it risks being reduced to a piece of paper if not put into action immediately.

Following the COP27 deal, countries decided that a Transitional Committee (TC) of 24 member countries would be formed to formulate recommendations for the upcoming COP28 summit in Dubai. The committee was tasked with deciding the functionalities of the fund as it remained shrouded with apprehension considering its previous failure to operationalise.

The biggest elephant in the room, how the funding will be conducted, persists to this day, as world leaders prepare to convene in Dubai for this year’s UN climate summit, COP28. The onus of providing the funds fell upon the developed countries but the very stratification of which are the developed countries was under scrutiny. China, for example, which is officially classified as a developing nation, is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world. The aim is also to exogenize funding by employing investment from non-state actors.

TC meetings were held throughout the course of 2023, though they failed to accomplish anything extraordinary. There have been many debates between developed and developing nations. The latter are not favouring the inclusion of the World Bank as the host of the Fund, considering it as a way in which developed countries could route the fund in a way that benefits them and are instead betting on a new institution to administer the fund and oversee its operation.

Another debate is with reference to the developed world giving special priority to Least Developing Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing Countries (SIDCs) nations, seen as an attempt to dilute their responsibilities of paying for the Fund.

Industrialised nations have historically moulded resources in a way that would benefit them. This time around, the developing world is determined to not just be at the receivers end but also guide the discussions in their favour.

The Stakes Are High at COP28

With COP28 approaching, all eyes are on developed countries to operationalise climate finance as soon as possible to overcome the rapidly accelerating impacts of climate change.

The COP28 Presidency maintains its demand for advancements in Dubai concerning the timely provision of annual funding for the $100 billion fund, conclusive commitments to the Green Climate Fund, fresh pledges to double adaptation finance by 2025, a successful replenishment of the Adaptation Fund, and the efficient implementation of the Loss and Damage Fund.

The Loss and Damage Fund is a testament to the acknowledgment on the side of the developed world that their path to development had irreversibly harmed the planet. Helping developing countries leapfrog the dark phase of development is the only way we can fight global warming.

While many celebrated the Fund as a euphoric triumph, many believe that it came “too little, too late”. It is pertinent that COP28 in Dubai forms a conclusive resolution to operationalise the Loss and Damage Fund as soon as possible.