As the world collectively turns towards more concerted and collective climate action, climate justice is becoming a similarly important issue. Some environmental activists argue that nations should share their responsibility to tackle climate change equally, yet equality doesn’t always represent a real distribution of equitable responsibility for global emissions. A country’s financial ability, technological prowess and even historical and moral inequities between Global North and South can muddy the waters. Equity becomes more important than equality so that countries can fulfil what the UN referred to as “Common but Differentiated Responsibility and Respective Capabilities.” A more just and equitable approach to tackling climate change may ultimately be more realistic than expecting every country to hit the same targets within the same timeframe.

—

Climate Justice and Finance: Should We Force Developing Countries to Adopt 100% Renewable Energy Within a Fixed Timeframe?

Carbon-emitting coal and other fossil fuels provide adequate electricity for all developing countries with an affordable price because only a cheaper electricity cost can maximise the net profit when electric energy consumption is so massive, as it is the case in developing nations worldwide. It is a trend that is only expected to grow over the next few decades.

Although solar energy costs on average between 3-6 cents per kilowatt-hour whereas electricity from fossil fuels costs 5-17 cents per kilowatt-hour, renewable energy still requires massive installation and maintenance costs. What’s more, fossil fuels’ efficiency rate ranges around 20-40% whereas solar energy is 15-22%. It’s highly questionable whether developing countries can maintain a high potential cost with a less efficient rate. Even though solar’s initial installation is cheaper, it would be a tall order for developing countries to offer upfront investment without international financial assistance.

Within in the debates surrounding climate justice, developing countries can only widely adopt renewable energies with the help of international assistance and affordable installation costs. But at the moment, renewable energy installations simply do not promise the same developmental and economic growth outcomes as fossil fuels do.

In a nutshell, developing countries deserve to achieve the same rate of economic growth, comfort and prosperity that the industrialised world began enjoying decades if not centuries ago. The problem is that wealthy nations were able to profit off of fossil fuels for decades without a worry about carbon emissions and climate change. If we want to keep global warming and climate change to manageable levels, developing nations would not be able to consume fossil fuels at anywhere near the same rate.

Resolving this climate justice paradox means making renewable energy installations cheaper and better prepared to handle the energy needs of a developing economy and growing population. But this is a task much easier said than done.

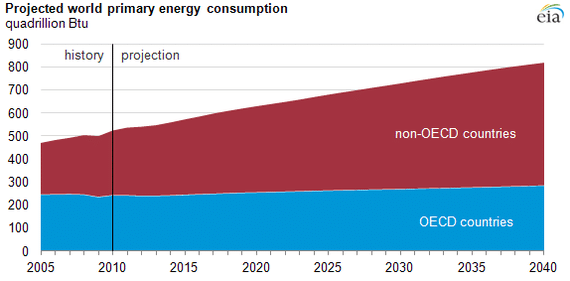

According to the United States Energy Information Administration, developing countries accounted for 54% of global energy use in 2010, and will rise to 65% by 2040. The annual growth rate of energy use in some countries, such as China and India, is predicted to be as much as 2.2%. In contrast, developed countries will only consume energy with a growth rate of 0.5% annually. The accelerating growth rate represents that around 57% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are contributed by developing countries, with India and China accounting for one third of the total GHG emission.

However, the aforementioned data hasn’t considered the fact that these developing countries will be more affluent in 2040. In other words, there will be a further increase in energy consumption for non-industrial use among these developing countries. On the flip side, the Chinese government has announced an ambitious green energy plan to alleviate its energy consumption. Between 2012 and 2017, the share of renewable energy in China’s energy supply grew by 38.2%. Nevertheless, fossil fuels accounted for 90% of China’s energy production in 2017. It shows that the existence of fossil fuels is a golden foundation for the development of Global South countries. In short, the factors above will impede global environmental targets in the future due to a practical demand for economic growth.

Global South countries are heavily reliant on fossil fuels as an economic engine because of their relatively cheap cost. Although a zero-carbon world sounds ideal, it’s only a utopian dream for many developing countries. As far back as the COP15 in 2009, there was an obvious disagreement between Global North and South countries. For example, Lumumba Di-Aping, Sudan’s delegate, condemned Denmark for not upholding neutrality and choosing to side with rich countries. The initial draft favoured wealthier nations with lower mitigation targets and set up a stricter regulation for developing countries. What’s more, COP15’s US delegates refused to offer public financial resources to assist the mitigation efforts of developing nations.

Although rich countries once planned to offer USD$100 billion dollars to developing countries by 2020, it has been proven that substantial effort is lacking due to internal debate regarding the distribution of financial assistance among all Global North’s countries. On the bright side, delegates agreed to extend the financial commitment to offer $100 billion dollars every year to 2025, beginning in 2022.

In this sense, it’s illogical to force developing countries to relinquish the use of fossil fuels within a short timeframe because their financial ability and domestic energy demand do not allow them to execute ambitious environmental commitments. However, Global North countries have refused to set up a binding financial assistance programme for developing countries because they are concerned about the use of financial resources and transparency among developing countries.

In other words, Global North countries will not financially assist Global South countries without strict regulation and scrutiny. Climate justice advocates would argue we should not force developing countries to adopt 100% renewable energy within a fixed timeframe when developed countries haven’t shown an aggressive action to mitigate their domestic GHG emissions or offer any effective financial assistance.

Leapfrogging Fossil Fuels

“Leapfrogging” means that developing countries may have the potential to skip the dirty phases of industrialisation with a full adaptation of modern and clean technologies. In other words, developing countries can acquire developed countries’ past experience to set up environmental policies in an attempt to avoid the abuse of fossil fuel once again. Can developing countries skip over fossil fuels entirely and adopt 100% green energy?

It is possible to adopt green energy with a leapfrogging approach if specific financial and geographic conditions arise. Most Global South countries are located in expansive regions with optimal access to sunlight and wind. It will be a feasible choice for countries to install massive solar panel facilities as sunlight is free and vast lands are usually available and not suitable for the development of agricultural soil. Although some critics once challenged a tremendous amount of upfront investment, the top 10 non-OECD emerging countries successfully absorbed $12 billion investment for solar technologies and $7.7 billion for wind power technologies.

What’s more, there is a high potential growth of renewable energy among these developing countries because approximately around 138.9 billion were allocated to the construction of clean energy capacities from 2010 to 2017. For example, the Thai government invited state-owned enterprises to invest approximately USD$6.4 billion in smart grids by 2036 to safeguard energy supplies in spite of financial concerns. The Thai government also plans to increase the proportion of renewable energy to around one third of total energy consumption by 2037. In this sense, it seems workable to adopt a leapfrog approach so that developing countries can skip the dirty phase of national development powered by fossil fuels.

Globally, the United Nation publicly announced the goal of Sustainable Energy for All by 2030 to fulfil universal access to green energies with higher energy efficiency. It has shed light on the prospect of green energy across the globe because it’s at least the first step towards achieving a robust share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. Although upfront investment is a concern, developing countries can at least grasp a glimpse of hope to transform their energy mix with a leapfrogging approach. This can save unnecessary time and cost to attain a developed country with abuse of fossil fuel energy in the future.

On the other hand, it’s unfair to urge developing countries to rigorously follow the same emissions-reduction standards when the US and European countries established economies with abuse of fossil fuel around a century ago. As recently as the COP26 summit this year in Glasgow, Chinese delegates urged the Western world to take real actions based on its historical emissions and responsibility. This double standard approach is somewhat unacceptable and unpersuasive to developing countries. Some climate justice advocates would even argue developing countries should have equal rights to consume fossil fuel energies for the sake of national development.

Developed countries should not put their fingers in every pie towards developing countries due to an economic disparity. Even though it’s a moral standard, developed countries should assist developing countries to tackle climate change. In short, it would be ideal to adopt a leapfrogging approach, but developed countries should also respect developing countries’ right to adopt energies and allow them to transform their energy mix within an adequate time frame.

Climate Change As a “Wicked Problem”

Climate change is a “wicked problem,” so called because of the complex and divergent responses to the crisis that different groups have put forward, thereby making it extremely difficult to solve. Our ancestors didn’t experience an imminent climate crisis that could directly threaten their survival as we do, and as a wicked problem, resolutions to climate change do not have a definitive strategy or “stopping rule.”

Under these circumstances, there are only good and bad solutions to tackle climate change, yet we have no chance to experiment with any proposed solution with a trial-and-error approach as we have no time and every trial counts. Climate change is vast, and its consequences, such as extinction and economic disruption, represent its unique set of wicked problems.

Last but not least, “planners are liable for the consequences of the solutions they generate; the effects can matter a great deal to the people who are touched by those actions.” In other words, our generations have to tackle climate change without sufficient past experience and with innovative solutions. We have only one chance to attain our environmental goal with limited knowledge and experience or the situation could worsen.

Although the definition of wicked problems allows us to understand that we are in the same international boat floating through a global climate crisis, it omits the importance of climate equity. In spite of sharing global responsibility, we should be more cautious about the responsibility between Global North and South countries. Global North countries should bear more responsibility than developing countries in consideration of their national wealth and moral responsibility.

After that, which strategy should we adopt to tackle climate change and climate justice? The aforementioned characteristics involves three types of strategies to resolve wicked problems:

- Authoritative: Only very few people can solve the wicked problem. Although this strategy can rule out unnecessary stakeholders to lower the problem’s complexity, the authoritative solutions may not be well discussed prior to any further action.

- Competitive: Different parties can present their preferred solutions. Although it creates a divided environment, this strategy can comprehensively weigh up various solutions before adopting the most suitable option.

- Collaborative: Different parties can collaborate with each other to develop the best possible solutions for all stakeholders. It’s tall order to integrate all preferred ideas and solutions but it can also create a strong information sharing environment.

The first two sections have directly revealed a contradiction between Global North and South, specifically in regards to climate justice and how the distribution of responsibilities is still being disputed. Many academics have pointed out that “those seeking to end the problem are also causing it.” First world citizens tend to emit higher emissions per capita in developed countries while third world countries are struggling to tackle climate change with very limited resources and domestic dilemmas. Essentially, having “no central authority” is the biggest underlying problem of this ongoing climate justice debate and contradiction.

Even though climate negotiations are frequently held on a global scale, an intrinsic layer of socio-political, moral and historical contradictions still exist in our global community. As such, both top-down and bottom-up approaches should be adopted to combat climate change regardless of massive vested interests as bottom-up approaches, such as private sectors and grassroots environmental activities, can devote innovative solutions for this wicked problem.

However, this collaborative approach faces the obstacle of hedonism that is market consumption. For instance, do retail stores really care about pollution from Black Friday? Will they adopt any significant measure to tackle climate change during the peak of hedonism at these events? If retail stores, which are mostly located in first world countries, show the smallest sense of responsibility in tackling climate change, there might be a glimpse of hope in resolving these wicked problems based on collaborative approaches.

So, should we adopt authoritative approaches? Though it may seem impossible for democratic countries, China demonstrates an interesting case in adopting this approach to resolve wicked problems. For example, China has been taking aggressive measures to accelerate the growth of electric car markets and is a pioneer in adopting green energies in order to transition into a green country. Some critics may argue that China’s decision is to avoid potential geopolitical risk in the Middle East and the sea routes, but it nonetheless demonstrates that the Chinese government can take massive steps, such as the 14th Five Year Plan to address climate solutions. Despite a lack of public involvement and discussion, these climate measures are better than sitting on their hands. However, China’s authoritative approaches may have a conflict and coexistence with global’s competitive approaches.

Should we adopt competitive approaches? It seems the best approach to tackle this wicked problem because all proposals can be well debated, modified and finalised by various stakeholders across the globe. But “time is running out” for further endless moral and historical debates as climate change is accelerating. While the competitive approach can create a constructive debate among countries and sub-national sectors, it seems that collaborative approaches are the imperative method to tackle climate change effectively.

Featured image: Ayush Manik/CGIAR Climate