When people mention climate change in everyday conversation, the melting ice caps and the effects of deforestation are perhaps the most discussed topics. But the loss of vegetation, or more accurately, how the loss of tree cover relates to climate change, is hugely important. Trees are often praised for being effective carbon sinks and producing oxygen, but they also provide shade and release water as perspiration. Therefore, while understanding and organising efforts to mitigate the harmful effects of a warming world is extremely important, there is also an often-overlooked aspect of climate change that is becoming much harder to ignore – heatwaves. In general, heat waves kill more people than hurricanes, tornadoes, or floods. Could planting trees be the solution in mitigating the impacts of heat waves?

—

Urban Tree Coverage and Inequality

Recent heat waves affected Western Europe in 2019, causing wildfires across Australia in 2020 and 2021, multiple instances of high heat in the North American Pacific Northwest in the summer of 2021, widespread, unreported heat waves across the African continent and similar events across Brazil and Paraguay in 2020 as well. While the reasons for the media’s decision to report on certain areas (and therefore the decision not to report on others) is a topic for another article, the issue remains that the entire globe is being affected by heatwaves.

The danger posed by the heat is not evenly distributed. Before delving into the reasons why this is, and the associated environmental benefit of planting trees in historically tree-deprived neighbourhoods, it is important to look into why these neighbourhoods have been neglected in this way.

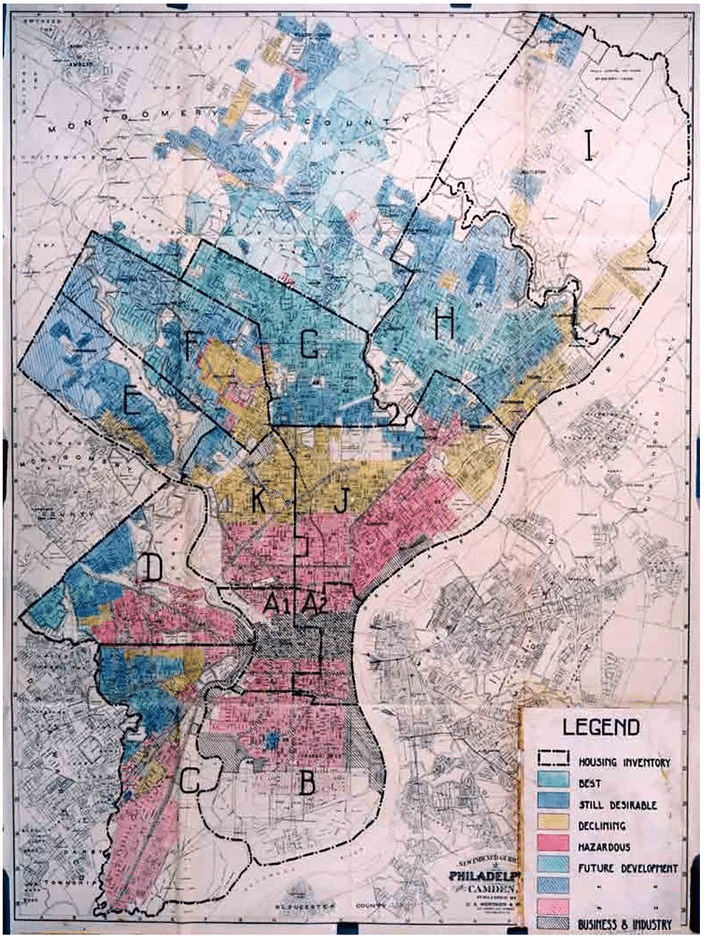

In the United States, during the era of the Jim Crow segregation laws, there was a legally-sanctioned practice in urban planning called redlining, the process of dividing up cities by neighbourhood along the lines of race, employment, and wealth. During the 1930’s, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) created ‘Residential Security Maps’ to accommodate the influx of people who could afford homes due to former US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s (FDR) New Deal programs, which introduced the 30-year mortgage with lower monthly payments along with low interest rates to increase lending. Neighbourhoods coloured green were seen as the best, followed by blue, yellow, and then red. The red neighbourhoods were designated as detrimental to the city. This legacy, far from being a historical relic, deeply affects the structure of modern American urban society.

This practice affected the levels of investment by neighbourhood, as both the government and private investors would deliberately seek to avoid areas deemed risky, thereby targeting wealthy, White neighbourhoods and neglecting impoverished neighbourhoods home to racial and ethnic minorities as well as working-class Whites. Similarly, “covenants” were legal obligations to not sell houses to Black people in certain (i.e., wealthy, White, “prestigious”) neighbourhoods. Redlined neighbourhoods were left with dilapidated housing, non-existent public transport, underfunded schools, sparsely distributed grocery stores (i.e., food deserts), public green spaces, and importantly, a profound lack of urban tree coverage.

Although the United States was used in this example, redlining was not confined to American cities. To name just a few, Canada also practiced redlining, and the systems of apartheid in South Africa and Namibia were also designed to legally enforce racially-based housing segregation.

The Role of Trees in an Urban Environment

Black asphalt, concrete, dark rooftops and tall buildings in urban areas all absorb large amounts of heat from the sun and create what is referred to as “urban heat islands”. This is exacerbated by heat emitted from the high concentration of automobile and industrial emissions in cities, particulate matter pollution that can also lead to adverse health conditions such as asthma, stroke, and cancer. Redlined neighbourhoods had highways built through them, exacerbating these issues. The increased temperatures found in urban heat islands are exacerbated by the short distance between buildings, which stifles the natural circulation of air. In addition, the use of concrete and dark surfaces retains the heat absorbed during the day, keeping nighttime temperatures higher than normal.

Green spaces are a very effective way to combat urban heat islands. Planting trees are effective at reducing temperatures due to the shade they provide in conjunction with the water they release when they perspire, which can cool temperatures by 2-4 degrees Fahrenheit (approximately 1-2 degrees Celsius). Jad Daley, the President and CEO of American Forests, said that planting trees reduce home energy usage for heating and cooling by 7.2% across the US, which decreases dependence on greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting fuels for temperature control uses, as well as reducing hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) released from air conditioning.

However, low income neighbourhoods are less likely to have widespread air conditioning installed in housing units, meaning they contribute less to overall HFC emissions, but at the same time are more susceptible to the harmful and potentially fatal effects of heatwaves. Conversely, wealthy residential neighbourhoods both have generally higher levels of tree coverage yet still contribute more to overall HFC emissions, relative to low income residential neighbourhoods.

Planting trees can provide large air filters, or carbon sinks. Urban trees provide 20% of carbon capture by trees in the US. Trees also play a large role in flood mitigation. In the US, one in 10 homes are at risk of flooding, in Canada it is one in 5, and the UK stands at one in 6 homes. Flooding therefore poses a large risk to human settlements, with already high and increasing rates of urbanisation. The same factors that create urban heat islands also prevent the natural drainage of water from rainfall.

Planting trees can also slow flood progress via a process called interception, where the canopy cover allows up to 30% of the rainwater to evaporate, preventing it from ever hitting the ground. Tree roots help the ground absorb water and disperse it throughout the soil surrounding the roots. In urban areas, where the ground is generally covered by pavement, these can both have a large positive effect on flood mitigation – reducing groundwater runoff in urban areas by as much as 80%. However, an issue lies in the fact that planting trees when they are young means that it can take approximately 30 years for them to grow to the size where they are able to provide cooling, carbon capture, and flood mitigation benefits.

Climate Change and Heat Wave Occurrence

As stated earlier, the danger posed by heat waves is not evenly distributed across geographical, wealth, income, age and racial lines. A person’s medical history, which can be largely impacted by these factors, is also a key determiner of level of susceptibility to heatwaves. Heat waves pose disproportionate danger to the elderly and those with pre-existing health conditions such as cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases. These conditions have high rates of occurrence in developed countries. In addition, pre-existing health conditions which increase susceptibility to adverse health effects caused by heat waves are concentrated largely within low-income neighbourhoods that have been affected by biased practices such as redlining.

The legacy of redlining in North America is multifaceted and enduring, and cannot be ignored in discussions about the social effects of climate change. Poor infrastructure in low-income neighbourhoods is a result of decades of deliberate neglect from the public and private sectors. This withholding of investment into infrastructure, services, and employment opportunities led in large part to the disproportionate levels of adverse health conditions seen in low-income communities today.

Comparatively absent healthcare infrastructure, less access to healthy food options in low-income neighbourhoods, in addition to the obstacles posed by increased travel time to grocery stores in urban food deserts, and less money to spend on gas to purchase the generally more expensive healthy options acts as a coercive force to consume unhealthy fast food. The expensive state of private healthcare in the United States also acts as an effective barrier to care for low-income communities, and contributes to generational cycles of poor health.

You might also like: The Cost of Subsidising Agriculture

The increasing regularity and intensity of heat waves, which are increasing in line with the warming of the average global temperatures, multiplies the negative effects of heat waves on low-income communities. These effects are compounded by comparatively less green space and urban tree coverage as well as less access to air conditioning, as discussed previously.

Some cities have resorted to opening city-run ‘cooling centres,’ large buildings that provide access to air conditioning to the general public. While these can provide relief from the acute adverse effects of heat waves during peak temperatures, they do not address or seek to correct the systemic causes of inequality in terms of urban planning, an issue that will only be compounded by climate change. These centres also contribute to the release of HFCs associated with air conditioning.

With the increasing rate of heat wave occurrence due to climate change, this method of treating the symptoms without addressing the systemic cause is untenable. According to Reuters in 2021, heat waves that used to be recorded once in 50 years are expected to now happen once every decade, on average. In the US, there were on average two heat waves every year in the 1960s. In the 2010s, the average was six. In addition to their increasing frequency, the length and intensity of heat waves is also increasing. This is reflected in the death counts associated with heat waves, and climate change, more generally.

In Paris, a climate change-induced heat wave in 2003 increased the chances of death by 70%. Therefore, although heat waves in recent years have made most of the headlines (even as some were not reported on), climate change-related heat waves are not a phenomenon that have developed within the last few years.

Toronto: An Urban Forest Case Study

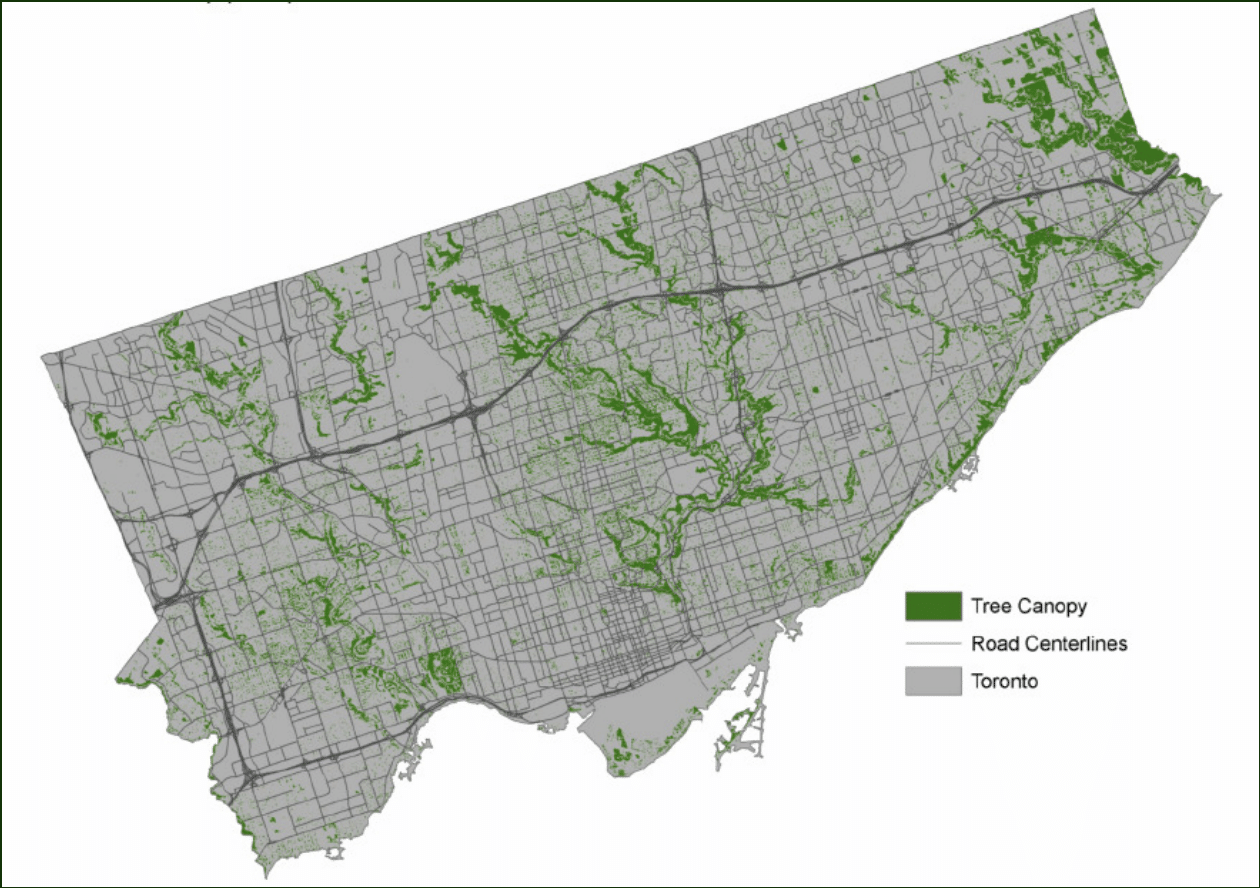

To demonstrate the argument of this article, Toronto, Ontario, Canada will be discussed. Toronto had an average tree canopy cover of 28-31% in 2018. This average alone does not tell the full story. Toronto’s Rouge National Urban Park, Canada’s first urban national park, takes up 75 sq km out of Toronto’s 630 sq km (approximately 12% of Toronto’s total area). It is a densely forested area which increases the canopy coverage average across the whole city.

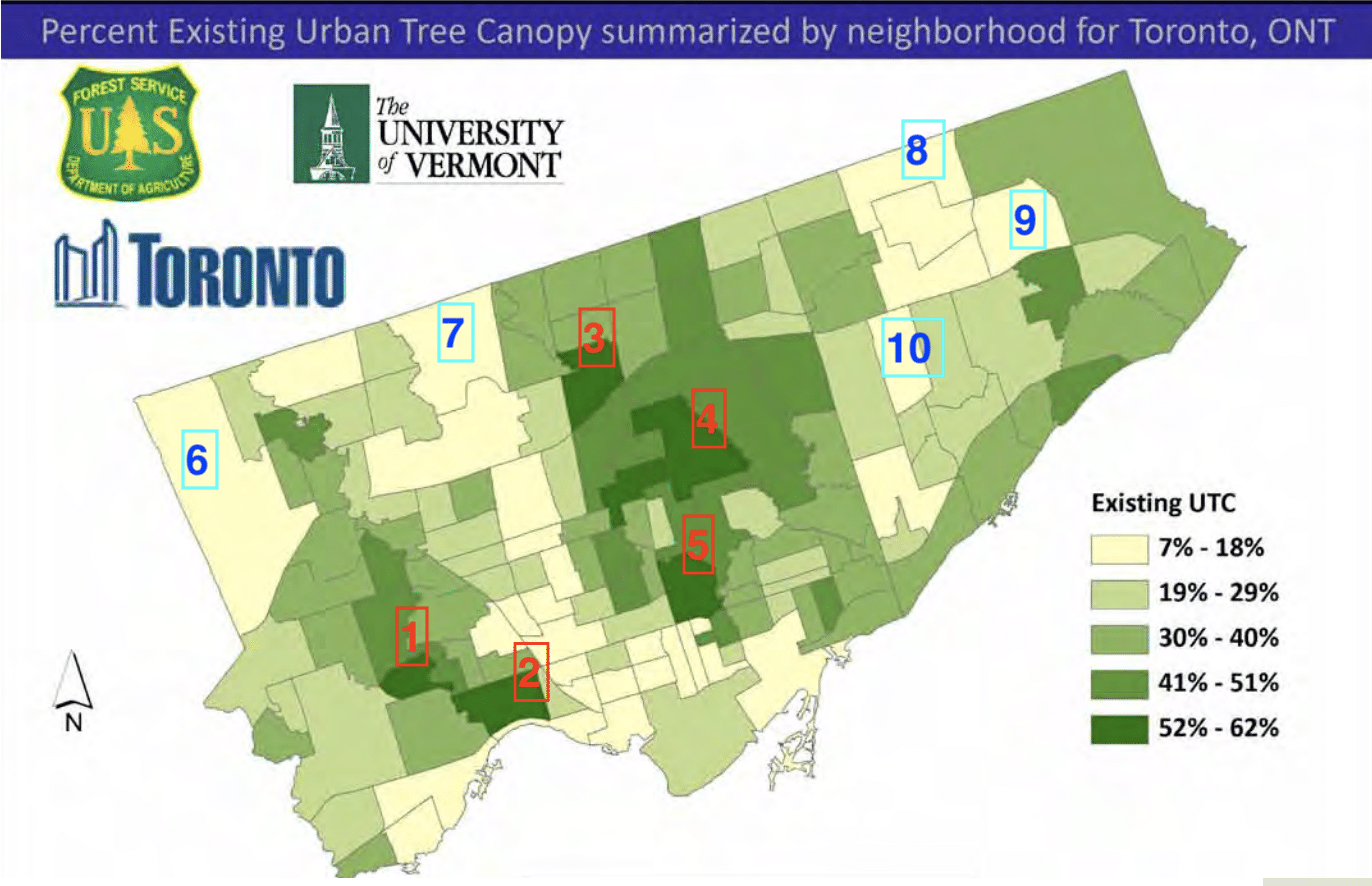

As of 2010, 60% of trees in Toronto are located on private property, compared to 34% in public parks, and only 6% lining streets. The distribution of trees on private property as well as city parks is in strong correlation to neighbourhood wealth. For example, the Rosedale, Bridle Path, and Hogg’s Hollow neighbourhoods have among the highest levels of tree coverage in Toronto. Aside from the Don Valley Ravine, Thorncliffe Park and Flemingdon Park are relatively deprived of green spaces, especially trees lining the streets, as compared to the neighbouring residential area of Leaside.

The darkest green areas correspond to The Kingsway (1), High Park (2), Lansing-Westgate (3), Hogg’s Hollow, the Bridle Path, and Sunnybrook Park (4), and Rosedale-Moore Park (5). According to Toronto census data from 2016, these areas had median family incomes of CA$192,638 (1), $122,603 (2), $104,954 (3), $266,931 (4), and $179,068 (5), respectively – well above Toronto’s median family income of $82,859.

The yellow-shaded areas listed six through 10 correspond to West Humber-Clairville with a median family income of $78,190 (6), Black Creek ($52,839) (7), Milliken ($65,240) (8), Malvern ($70,001) (9), and Dorset Park ($66,989) (10). In addition, according to the same census, these neighbourhoods have visible minority (i.e., non-White) populations of 12% (1), 19.1% (2), 41.3% (3), 30.2% (4), 18.1% (5), 82% (6), 80.9% (7), 96.5% (8), 89.5% (9), and 77.7% (10) against a 51.5% average across Toronto. A much more detailed analysis, such as the study published by the American National Institute of Health (NIH), also finds this to be a deeply entrenched trend. Therefore, a correlation likely exists due to the legacy of intentionally discriminatory practices in urban planning and investment patterns. This could suggest that the legacy of racial proximity to wealth – being in correlation to the population of White residents in a given neighbourhood – is still relevant.

Between 1977-2001, there have been, on average, 120 heat-related deaths per year in Toronto. The number of days in a year where temperatures rise to over 30 degrees Celsius is a metric used to predict heat-related morbidities. Temperatures in areas without tree canopy coverage temperatures can be 25 degrees Fahrenheit cooler. Chronic health conditions and comorbidities are concentrated in low-income neighbourhoods. According to the NIH, these neighbourhoods, which generally have had less public and private investment, sparse tree cover, and a higher a percentage of non-White residents, have been left by the government to deal with the heat-related conditions and deaths that disproportionately affect them. Therefore, there is a public health and safety rationale in increasing canopy coverage in low-income neighbourhoods.

Planting Trees in Low-Income Communities

Rather than being indicative of personal faults (as poverty and poor health are often misattributed to), and rather than being due to a structural ‘failure’ (as lack of green space is often described as), the deeply interconnected cycles of poverty, poor health, a lack of tree coverage and green space are interconnected results of coordinated efforts between the public and private sectors. Therefore, pressure must be applied to both the government and private investors and financiers to invest in repairing the damage caused by redlining over multiple generations.

Planting trees in low-income neighbourhoods is becoming a more widely recognised necessary step to achieving greater urban equality as well as a health and safety measure, with the increasing occurrence and intensity of heat waves projected to increase. For example, academic studies on the relationship between urban tree coverage and income, race, and other forms of inequality have been published since 2017. Advocacy groups have also taken action on getting fundraising and planting trees in urban and rural areas across the globe. Joint-efforts between NGOs and academia are powerful forces in shaping and influencing international norms, especially in the field of climate change.

The City of Tacoma, in Washington State, USA has taken a serious approach to reforestation policy. They aim to increase city-wide canopy coverage to 30% by the year 2030. Tacoma intends to do this through the participation of its citizens, along with partnerships with the private sector and publicly owned corporations like Metro Parks Tacoma. This poses the potential challenge of reconciling the private sectors’ profit motive with a potentially non-profitable venture that benefits low-income and ethnic and racial minority communities, who have traditionally been marginalised by these same public and private sectors. NGOs such as the Tacoma Tree Foundation, who also partners with Tacoma Parks, have been involved in community-oriented initiatives in plating trees. In order to accommodate the pressures placed upon them by NGOs and the public, the government intends to provide ‘worthwhile’ incentives to these private sector actors in order to attract investments.

Tacoma stresses the importance of city-wide green space for its role in mitigating the effects of climate change as well as making the city more pedestrian-friendly, which also encourages walking as a means of transportation, decreasing automobile usage. Tacoma has also stated that they intend to promote community-oriented tree stewardship programmes to foster community growth and engagement. However, the City of Tacoma still ought to ensure that this increase in green space is equitably distributed, with the majority of reforestation being targeted in areas that have been neglected.

Featured image by: Biophiliccities