In 2006, housing prices in the US hit an all-time high, fuelled by speculation, exuberant spending, and high demand despite a rapidly falling supply. When some homeowners were inevitably unable to pay back their mortgages or federal loans, many homes foreclosed, leading to a dramatic decline in housing prices. This caused the so-called housing bubble to burst, partly contributing to the worst financial crisis in recent US history that was felt across the world. Financial bubbles have affected everything from the housing sector to the Internet, cryptocurrencies and comic books, and as we move towards a low-carbon future, we may soon be faced with another bubble: the carbon bubble. What is a carbon bubble, and how bad could it be?

—

Financial bubbles occur when the price of an asset becomes warped by implausible projections of the future. Often, shareholders may speculate that their assets will continue to be valuable, maintaining high stock prices and consumer confidence. Sometimes, however, demand and market confidence will be met with real-world situations that devalue the asset. In the case of the housing bubble, a combination of federal spending and extremely generous loan policies from banks allowed demand for houses to rise, even though the actual supply of homes was dwindling.

When faced with a bubble, shareholders can either play it safe and shift investments away from the straggling asset, or they can double down and speculate that it will maintain or increase its value. More often than not, this eventually leads to a bubble bursting, and in the worst-case scenarios, a financial crisis and market crash.

In the US, the housing market crash is regarded to be one of the main causes behind the 2008 financial crisis that afflicted the entire world. In addition to the stock market crash and a global recession, the housing crisis in the US caused 8.7 million jobs to be lost, almost 500 banks to fail and over 8 million homes to be foreclosed.

The impacts of financial bubbles are always temporary, and markets tend to reset after a period of stagnation or recession. The severity of bursts are more volatile, depending on the sectors involved, how many people are affected by the crisis and whether or not the consequences cascade globally. But regardless of how long a bubble burst-induced recession lasts, people suffer because of it.

The 2008 financial crisis was bad, but the next bubble might be even worse. Investors often speculate on the continued growth of assets that have historically done well for them, not always acknowledging the pace of technological change and inevitable shifts occurring in markets. As economies and governments progressively, albeit painstakingly slowly, cut their ties to fossil fuels and transition to low-carbon technologies, could we be faced with a new financial crisis, this time involving a carbon bubble?

Are We Done With Carbon?

Much like when fossil fuel-powered cars first displaced the horse economy a century ago, the world is on the verge of a similar disruption, this time involving low-carbon technologies ranging from solar panels and wind turbines to electric vehicles and batteries with immense storage capacity. These technologies can and already are displacing the smokestacks, internal combustion engines and pipelines that have defined our modern era, and not a moment too soon.

Simply put, we desperately need these technologies. Burning fossil fuels is releasing more and more carbon into our atmosphere, warming our planet to degrees not seen in millennia. This is already causing severe weather impacts, agricultural failure and biodiversity loss across the globe, and making several parts of the world starkly uninhabitable.

Some impacts of climate change may well already be locked in, but the more carbon we avoid putting into the atmosphere now, the more liveable our future will be. 1.5°C of warming is bad, but it is much better than 2°C. And as bad as 2°C would be, 3°C would be unimaginably worse. Every particle of greenhouse gas we avoid putting into the atmosphere counts, because every fraction of a degree’s worth of temperature rise counts.

This is why it is so important to shift away from fossil fuels as soon as possible through every technological tool we have at our disposal. Every time someone decides that their new car will be electric instead of oil-powered, that is just a little less carbon that could have been injected into the atmosphere. And every time a power company or government decides to commission a solar farm instead of a coal plant, that’s even better.

From a humane standpoint, these are not difficult decisions to make, and it’s not difficult to see where the future might go. Renewables and low-carbon alternatives are better for the planet, for our health and for that of every living thing that may exist.

From an economics standpoint, fossil fuel companies and some politicians have long entertained the notion that carbon-free technologies are too expensive to implement and would cause a financial crisis. Were this correct, then economically speaking they would be right to be skeptical about carbon-free technology. If there is a bigger profit margin to be made from a perfectly cheap pile of coal lying around, solar or wind could never break into the market.

But of course, this argument is simply untrue. A 2021 report by the International Renewable Energy Agency showed that the cost of large-scale solar power has fallen by more than 85%, while onshore wind has fallen almost 56% and offshore wind has dropped 48%. In 2020, solar and wind power’s levelised cost of energy (LCOE, how much it will cost for a power plant of a specific energy source to generate electricity over the course of its lifetime) fell below that of coal and natural gas in most of the world, and the International Energy Agency also released a 2020 report that showed how cost competitive renewable energy had become with fossil fuels.

This trend is expected to continue. Two thirds of solar and wind farms built in 2020 will provide cheaper electricity than even the cheapest coal plants, especially in places like Europe, the US and India, where building a new coal plant will become much, much more costly. Given its high cost, and the promise of renewables, around three quarters of plans for new coal plants have been scrapped since the Paris Agreement to mitigate global greenhouse gas emissions was signed in 2015.

More government regulations on burning fossil fuels in recent years have made the activity less profitable, but the rapid decline in cost for renewable energy is primarily due to organic market forces.

Renewable energy sources, a new and rapidly evolving technology, follow learning curves, which means that the more renewable energy installations are built, the more costs will fall. Cost declines are aided by a number of factors that accumulate as more wind and solar farms are installed, including more research and development to improve efficiency, economies of scale creating better specialisation and simply learning by doing as companies develop incremental improvements to industrial operations, installation procedures, and sales and financing processes.

Renewables benefit from learning curves because they are new technologies with a high ceiling for improvement. The price of electricity generated from fossil fuels, meanwhile, does not. Due to learning curves, many project that the price difference between expensive fossil fuels and cheap renewable energy will only become larger as time goes on.

So from an economics standpoint, markets are telling us that a transition towards renewables is inevitable, and from a common sense standpoint, we know that we should be investing more of our resources into renewable energy to preserve our future. Good news, right?

Yes, but what happens to all the leftover fossil fuels? What will happen to the infrastructure and fossil fuel reserves that have benefited from decades’ worth of capital investment, but have suddenly become stranded assets, unable to turn a profit? A carbon bubble is what happens, and it might be much larger than we think – potentially equal to the housing bubble that caused the 2008 financial crisis.

The Carbon Bubble

The notion of a carbon bubble is based on our knowledge that 2°C is the absolute maximum amount of temperature rise we can cope with. Any more than 2°C, and the future frankly becomes too nightmarish for a carbon bubble to even register as a cause for concern.

To stay under that benchmark, ideally far under it, we would only be able to burn a certain amount of fossil fuels which release carbon into the atmosphere. Any more than that, and we are basically over-budget.

If we were to extract and burn all the remaining fossil fuel reserves in the world, global temperature averages would warm well past 2°C. This has been called ‘exceeding our carbon budget,’ the finite amount of carbon we can release into the atmosphere. The 2°C ceiling, which has now been largely amended to target a temperature rise of less than 1.5°C, is what we have to play with during our energy transition, but if we were to burn through all the fossil fuels that we could conceivably extract, we would be vastly over-budget.

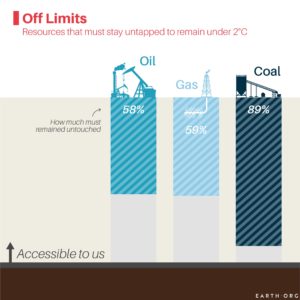

A 2021 study published in Nature proved that, to have a 50% chance of staying within a 1.5°C temperature rise scenario, 60% of remaining oil and fossil methane gas reserves and 90% of coal reserves must remain un-extracted by 2050. All these remaining reserves, the so-called ‘unburnable carbon,’ create a fossil fuel overhang of remaining reserves that we cannot touch.

How much ‘unburnable carbon’ still exists in remaining fossil fuel reserves/ Data by Welsby et al/ Graphic by Earth.Org

The carbon bubble problem arises when we consider that all those reserves – every drop of oil and eventual particle of atmospheric carbon – are currently included in the valuation of the companies that own them. Basically, unless we want to exceed our carbon budget, these companies are massively overvalued. Every major oil and gas corporation, which are all listed on the stock exchange and in which countless people are invested, are valued on the basis that we are going to burn through all of our existing reserves, because that is the economical thing to do. If you own an asset, even if it is unburnable carbon, responsibility to shareholders means that, in theory, the company that owns it has to profit from it.

This leads to two potential outcomes. On the one hand, fossil fuel companies burn through all their existing reserves, blow past our carbon budget and cook the planet beyond recognition. Alternatively, governments step in with regulations and stop companies from extracting unburnable carbon, which would make these massive fossil fuel corporations extremely overvalued, basically overnight. The fossil fuel company you are invested in becomes the house you spent your savings on, and all of a sudden, that house has no value anymore.

Who is complicit in creating this bubble and potential financial crisis? Well, it isn’t only the fossil fuel companies, but also the large and respected monitoring agencies that provide updated measurements of different energy sources’ LCOEs. The think tank RethinkX published a recent report that highlights how the International Energy Agency, the US Energy Information Administration, Wall Street analysts and others have routinely been overvaluing the LCOE and associated costs of conventional coal, natural gas and hydro power plants for years.

Investors, regulators and policymakers rely on these agencies’ assessments to make decisions, but have been misled to think that fossil fuels and older forms of renewable energy plants produce much more electricity than they actually can, and are therefore far less expensive than they actually are, making those power plants appear as good investments when they really aren’t.

The RethinkX report points out that since 2010, $2 trillion dollars have been invested in fossil fuels and nuclear power based on misleading assumptions on the value of these industries. These risky investments have only been exacerbated by even more uncertain speculation in the effectiveness of unproven technologies like carbon capture and storage. The report estimates that the LCOE of coal, gas and hydro has been overvalued by as much as 400%, and that the resulting carbon bubble could swell to be worth over $1 trillion in stranded assets by 2030.

Shrinking the Carbon Bubble

But wait, how could a carbon bubble impact me if I’ve never invested any money in fossil fuel companies?

Even if you have not personally invested any money in fossil fuel companies (and hopefully you haven’t), it is very likely that your pension fund has. A 2020 study found that pension funds in OECD countries could collectively manage anywhere between €238–828 billion in fossil fuel assets (up to USD$978 billion). In the UK alone, despite promises to divest from fossil fuels, £10 billion are still invested in fossil fuels from local government pension funds. Even if very few of us are shareholders in fossil fuel companies, we are all, directly or indirectly, stakeholders in their fortunes and misfortunes.

The carbon bubble has investors concerned. In 2013, unreasonably prescient British investor Jeremy Grantham, who manages over USD$106 billion in assets, pulled out of all coal and unconventional fossil fuel investments, such as tar sands.

“The probability of [fossil fuel companies] running into trouble is too high for me to take that risk as an investor,” Grantham said, adding that: “If we mean to burn all the coal and any appreciable percentage of the tar sands, or other unconventional oil and gas then we’re cooked. [There are] terrible consequences that we will lay at the door of our grandchildren.”

Much like with the housing bubble and subsequent financial crisis, there are no easy answers here. We need to eliminate fossil fuels from our energy grids, and to do this, some of the biggest and wealthiest companies in history cannot touch the vast majority of their assets.

The best-case scenario for a way out is a managed decline to shrink the bubble as much as possible before fossil fuels, and also nuclear and hydro power, become financially unviable, completely outcompeted and disrupted by modern renewables. This has to come from governments, who should ensure that the public become gradually divested from these archaic forms of energy generation. At the same time, governments need to support the expansion of renewable energy sources that will replace them.

It is uncomfortable to think of, but most people are indeed financially invested in fossil fuels, either through pension funds or even regular unassuming asset managers. In 2021, half of the world’s 29 largest asset managers did not have a policy in place to exclude coal as an asset. And while many asset managers have pledged to be leaving coal behind, the world’s three largest asset management groups, BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street, still managed over $300 billion worth of fossil fuel investments as recently as 2019.

Without decisive action to eliminate fossil fuel-related assets from their portfolios, the carbon bubble will impact these firms, within which normal people from all over the world are invested. And even if we are not directly invested in the fossil fuel companies themselves, most of us are invested in the infrastructure that supports them, from pipelines to roads and railways. To minimise the impact of this impending financial crisis and bubble, governments need to ensure that asset managers and pension funds worldwide are divesting from fossil fuels now.

There are some positive signs. In 2020, New York State’s pension fund worth $226 billion, one of the world’s largest and most prolific investors, announced to be dropping most of its fossil fuel stocks by 2025, and by 2040 will have sold all its shares in companies that contribute to global warming. “New York State’s pension fund is at the leading edge of investors addressing climate risk, because investing for the low-carbon future is essential to protect the fund’s long-term value,” Thomas DiNapoli, the state comptroller, said.

New York’s decision to divest its pension funds from fossil fuels follows similar action taken in Ireland and Sweden. Norway, which manages the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund at $1.4 trillion, also sold the last of its stocks in fossil fuel companies in Januray 2021. The following September, the Norwegian government upped the stakes by requiring that all companies in its portfolio maintain strict 2050 net-zero targets.

On an individual level, we can all become more cognisant of where our money is going. Fossil Free Funds is a search platform that can tell users whether their pension funds, mutual funds or individual investments are tied to fossil fuels, and lists options that provide guilt- and risk-free alternatives.

Divesting from fossil fuels isn’t only the morally right thing to do, it is a financially wise decision, and people still have the agency to protect themselves. Ultimately, however, government policy will be needed to ensure that the financial impact of new technologies taking over from fossil fuels be minimised. The carbon bubble has the potential to cascade into a much bigger financial crisis, but it doesn’t have to, as long as governments are willing to think long-term and consign fossil fuels to history today.