On April 19, young climate activists around the world will take to the streets to demand climate action and justice under the motto “fight for a world worth living in.” Earth.Org spoke with Fridays for Future USA’s Johanna Speiser and Winona Freed about the upcoming global strike’s significance and the future of climate change protests.

—

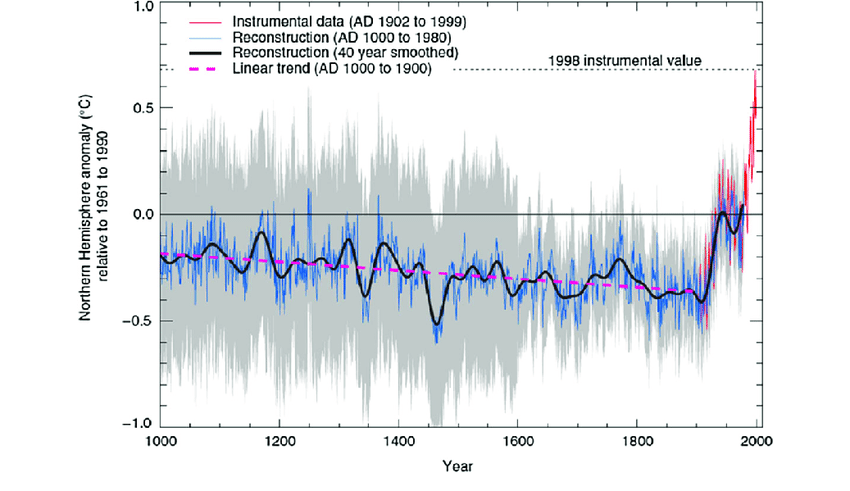

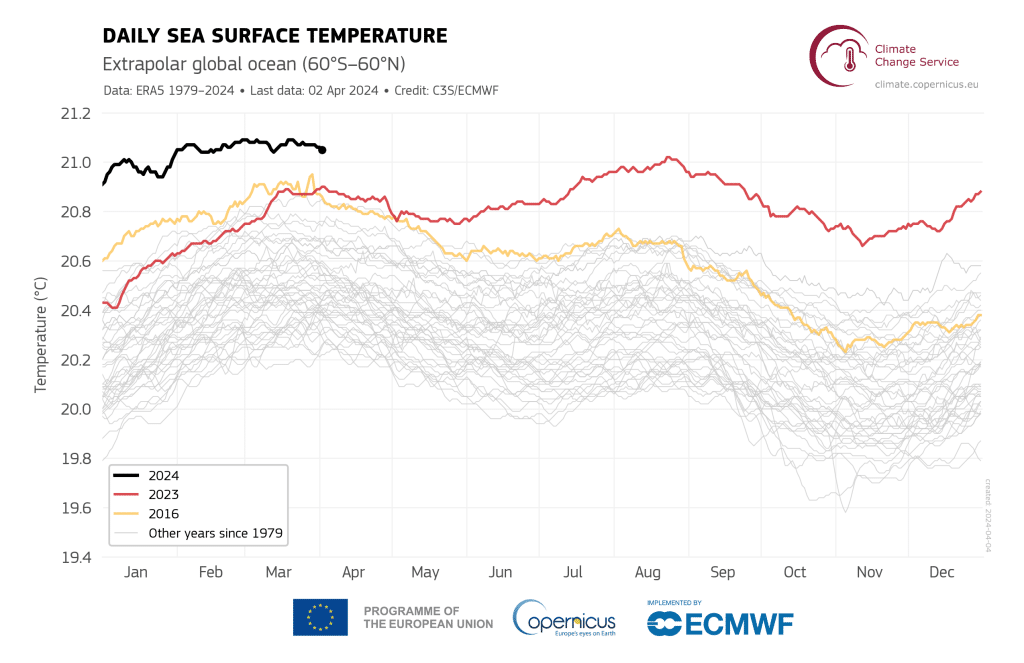

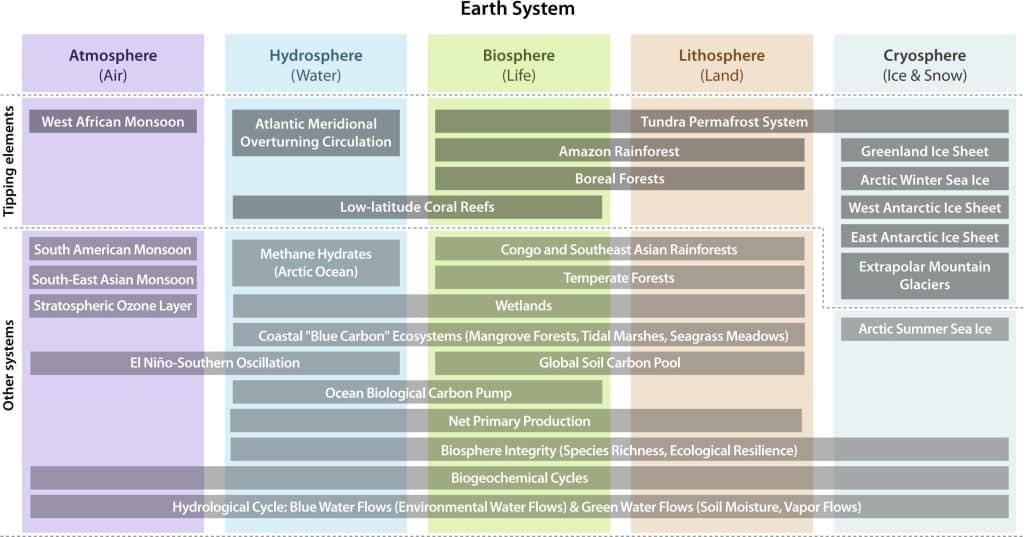

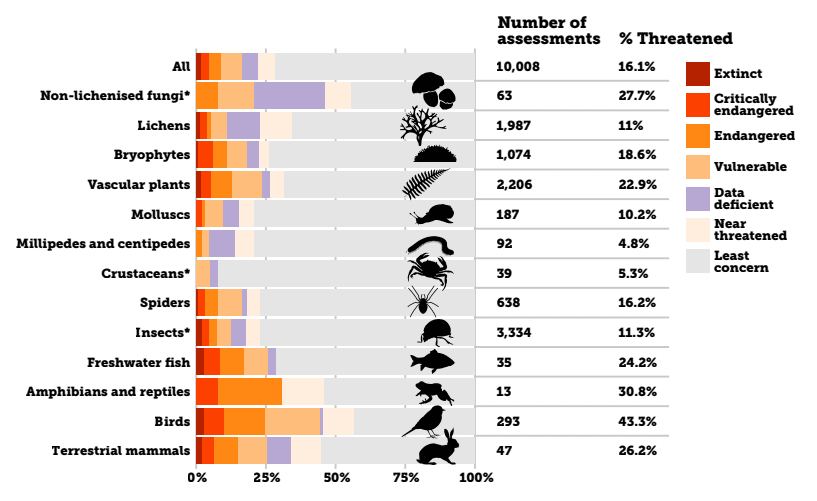

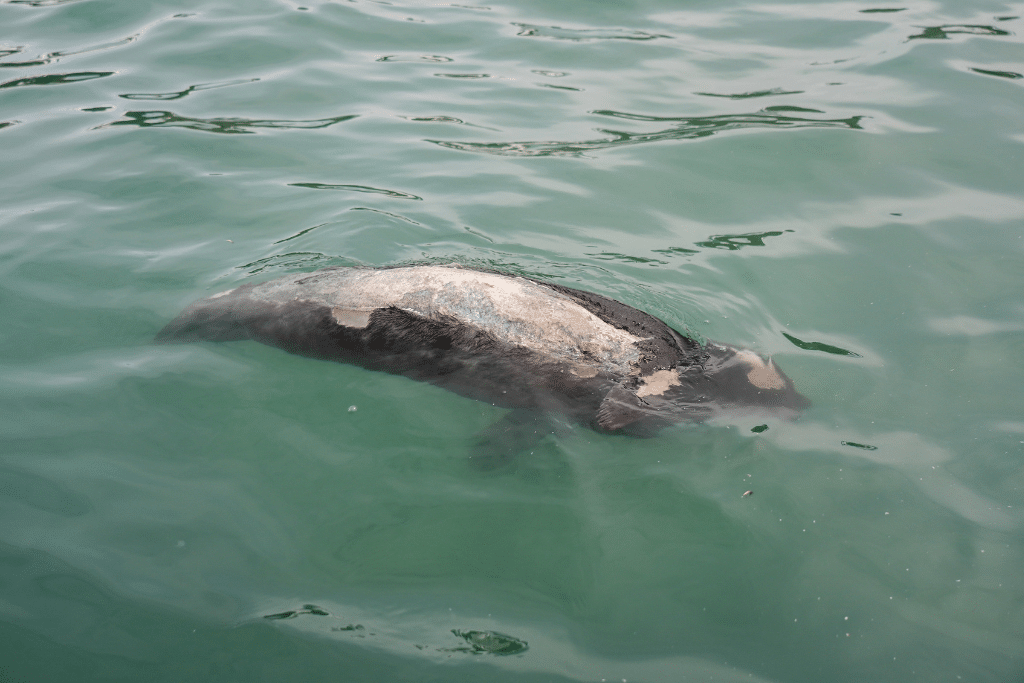

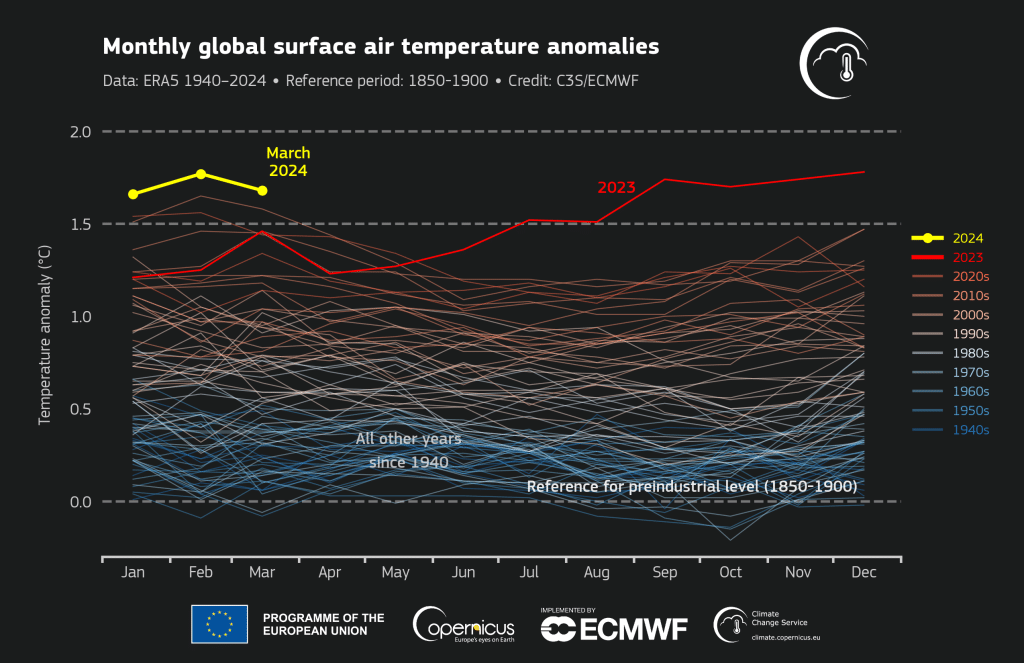

Against the backdrop of relentlessly rising global temperatures and greenhouse gas emissions, widespread suffering from the devastating impacts of increasingly frequent and intense extreme weather events, and the first signs of collapse of key ecosystems, young climate activists around the world are saying enough is enough.

On April 19, hundreds of thousands of young, frustrated, climate-conscious people from all corners of the world are expected to respond to Fridays for Future’s call to take to the streets and demand urgent climate action and justice for all.

With the Global Day of Action (GCA) nearing, Earth.Org turned to Johanna Speiser and Winona Freed, coordinators of the strike for Fridays for Future (FFF) USA, to discuss its significance and how the youth climate movement is evolving and adapting to constantly changing social and economic dynamics amid a rapidly deteriorating climate crisis.

“Globally, the [GCA] objectives are to remind decision-makers and the wider public of the urgency of the climate crisis and the need to ‘End Fossil Fuels’ for a livable future for the youngest and future generations. By showing our presence in the streets we are conveying that many people no longer want business as usual and realize that another world is possible,” Speiser told Earth.Org.

The protest comes just months after an estimated 50,000 to 70,000 people from all walks of life joined the ‘March to End Fossil Fuels’ in New York City last September ahead of the United Nations General Assembly, demanding that world leaders take decisive action to limit global warming to well below 1.5C as outlined in the Paris Agreement.

Fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – are by far the largest contributor to global warming, accounting for over 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90% of all carbon dioxide emissions. But despite the “historic” COP28 deal to “transition away” from fossil fuels, data shows that we are well off track from our climate commitments.

All three main greenhouse gasses – carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide – reached record highs in 2023, albeit growing at a slower pace than previous years. What’s more the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP) 2023 Production Gap Report suggested that while major producer countries have pledged to achieve net zero and take steps to reduce emissions from fossil fuel production, none have made commitments to decrease coal, oil, and gas production in alignment with the global goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. Instead, current production plans indicate that governments will generate 110% more fossil fuels at the end of the current century than the amount required to keep on track with the Paris target.

You might also like: Will We Ever Be Able to Go Without Fossil Fuels?

The main consequence of this inaction is that the planet’s atmosphere and seas are warming at an unprecedented rate and in a way that climate scientists find harder and harder to predict and understand. In a recent interview with Earth.Org, Swedish Earth scientist Johan Rockström, the lead author of the planetary boundaries framework, said that what happened in 2023 “was beyond anything [scientists] expected and no climate models can reproduce [it],” making scientists “very nervous.”

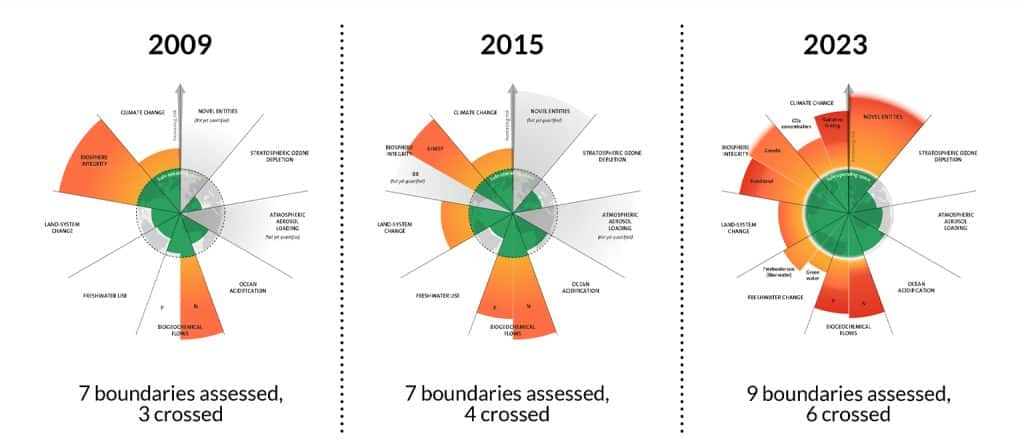

“A large part of these Global Days of Climate Action is to raise awareness. 2023 was the hottest year on record yet many people are not aware of this,” said Speiser. “Our way of life is currently not sustainable within planetary boundaries and we are facing wide-scale ecosystem collapse. As soon as people realize this they want to act and that is the other important part of the GCAs, to grow our movement and provide people with a motivating and joyful space to take action.”

From Solo Protest to Global Movement

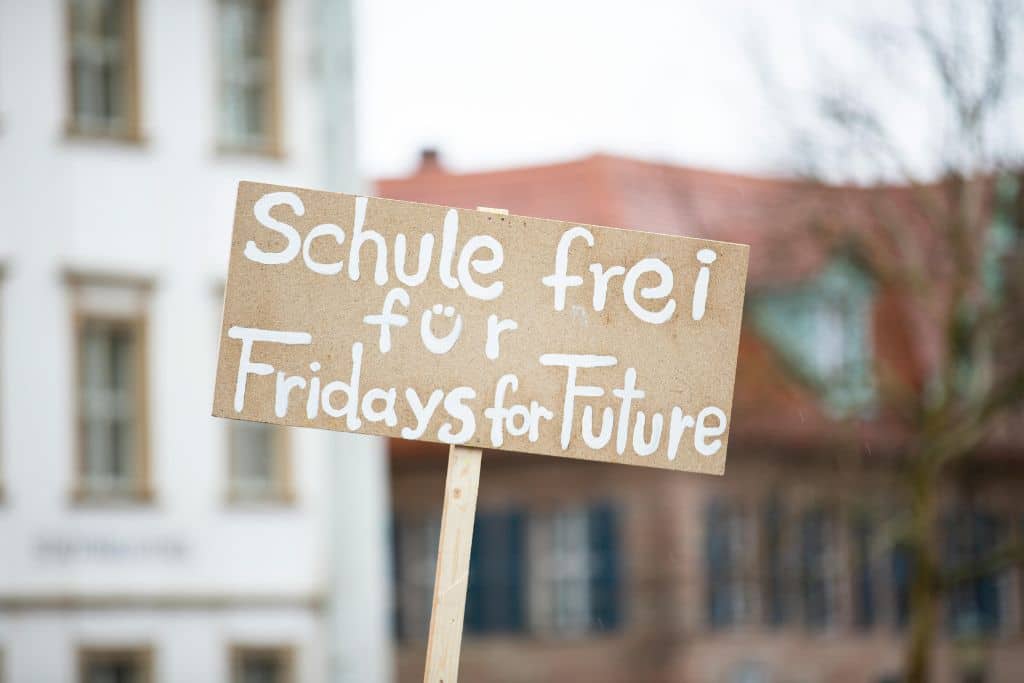

The iconic photos of 15-year-old Greta Thunberg‘s solitary protest outside the Swedish parliament marked the transformative start of the global youth-led climate movement Fridays for Future. From her initial campaign in August 2018, where she expressed frustration with her country’s politicians’ inadequate response to carbon emissions targets, the movement quickly gained momentum. Within months, over 20,000 students worldwide had joined the Fridays for Future strikes, culminating in nearly 6 million people participating in the Global Week of Climate Action a year later, demanding urgent climate action and justice.

The pandemic posed both opportunities and challenges for young climate activists. At its peak when Covid-19 emerged, FFF had millions of activists worldwide united in urging politicians to address the climate crisis. Though unable to hold large marches, they adapted by bringing the strike online using social media and hashtags like #DigitalStrike. They utilized petitions, live broadcasts, webinars, Instagram, TikTok, and virtual meetings to expand their reach and make the movement more inclusive globally. While depriving the movement of its visual impact – pictures of hundreds of thousands of young people flooding streets around the world – the pandemic also shaped public opinion on climate change as a crucial existential issue.

“The pandemic initially dampened the moment we had been building for the past one and a half years. We were unable to protest in person and had to move everything online, which resulted in a lot of local groups dissolving and people slowly dropping out,” said Speiser.

“[But] we have seen a resurgence in new young people getting involved directly after the pandemic. With lockdowns forcing people to take a step away from business as usual, some found the time and space for climate activism for the first time. One of the members in my local group said that after Covid they felt that ‘now I have no excuse anymore, I need to go and do something.’ The current online structure that FFFUSA uses, the way we organize and communicate digitally, also came out of the pandemic.”

Nowadays, Fridays for Future is a decentralized movement with hundreds of active local chapters around the world.

You might also like: Fridays for Future: How Young Climate Activists Are Making Their Voices Heard

“The heart and soul of our movement are local groups who do a lot of the ground work, organize protests and engage with people in their communities. The national and international FFF network is mainly there to provide support for, and connect, local groups,” explained Speiser.

She said that one of the main focuses internationally is the need to recognise that people and communities are disproportionately affected by climate change.

“It is necessary to address the climate crisis from a historical perspective, which means viewing it in the context of colonialism and recognizing the responsibility the global North, and especially the US which is the historically largest emitter of CO2, has towards the Most Affected Peoples and Areas,” said Freed, who is part of FFF Las Vegas local group. “Growing the movement and making policy changes at the local level greatly impacts national and global policies.”

While sharing common objectives and demands, local groups also focus on pressing issues affecting their nation or local communities. The FFF US chapter, for example, provides support for a network of local groups based in cities across the country, collaborates with other grassroots initiatives such as Sunrise Movement, Reclaim Earth Day, and Campus Climate Network, and is part of Youth v. Fossil Fuels, an alliance of youth climate groups. The group hopes to use April 19 to call on President Biden to declare a state of emergency, finally acknowledging the climate crisis for what it is, Speiser said.

“In the USA specifically we are hoping that the GCA will, as part of a larger escalation arc including events planned in the summer, help raise the pressure on President Biden to take climate action.”

The group is demanding that the Biden administration turns the current pause on liquid natural gas (LNG) permits into a full stop and backtracks on both the US$10 billion proposed natural gas liquefaction export terminal CP2 LNG in Louisiana and the controversial Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP), a natural gas pipeline in the state of Virginia currently under construction. The group is also calling on the government to invest in a just and equitable transition away from fossil fuels that takes the rights and needs of the communities most affected by the climate crisis into account, Speiser explained.

Dealing With Climate Skepticism

Climate activism often faces criticism or skepticism from certain quarters, and while it is true that an increasing number of people recognise climate change as a serious and imminent threat to the planet and acknowledge the indisputable role humans played in exacerbating this global crisis, climate denialism remains a reality, especially in the US.

“How we deal with skepticism depends on where it’s coming from. Many of our FFF local groups hold teach-ins which provide education for those seeking the information. If it’s outright denial with no intention to have a meaningful conversation, then the best option is just not to engage,” said Speiser.

Climate activists have also repeatedly come under fire for the tactics they use to draw attention, particularly when they resort to public disobedience and disruptions such as road blockades, with polling suggesting that public disobedience tactics and vandalism often lead to backlash rather than widespread public support. Extinction Rebellion UK, a notorious climate protest group known for civil disobedience actions such as occupying roads and bridges in central London and blocking oil refineries, announced last year that it would “temporarily” move away from disruptive tactics.

More on the topic: Are Climate Activists Reaching Too Far?

“Our goal is to empower those who want to act but don’t know how and to show that climate justice is an issue people care about. Similarly, our goal is not to defend ourselves and argue that our way of protesting or drawing attention to the climate crisis is the ideal or best way. We acknowledge that many forms of action are needed to create the social shift necessary…individual change, systemic change, peaceful civil disobedience and direct action, lobbying Congress are all valuable courses of climate activism,” said Freed.

“When it comes to the type of skepticism that agrees with our general sentiment but criticizes specific ways we go about our actions, then our response is often, ‘thank you for pointing that out, do you have an alternative you would like to propose?’ or an encouragement for those ‘skeptics’ to start organizing themselves and creating the types of actions they want to see.”

To find out more about the April 19 Global Action Day, visit fridaysforfuture.org/april19/

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us