The world population has reached 8 billion and is expected to keep climbing at a rate of about 1% every decade until at least 2050. A growing number of people means having more mouths to feed. However, the way we eat has changed drastically in recent years, with an increasing demand for resource-intensive and environmentally impactful food. Modern eating habits have put a strain on the planet’s resources, compromising global food security and contributing to the acceleration of global warming. In this article, Earth.Org reflects on the importance of safeguarding the planet’s precious food resources.

—

What Is Food Security and Why Does It Matter?

There are many definitions of global food security. The United Nations Committee on World Food Security (CFS) describes it as a situation in which “all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life”.

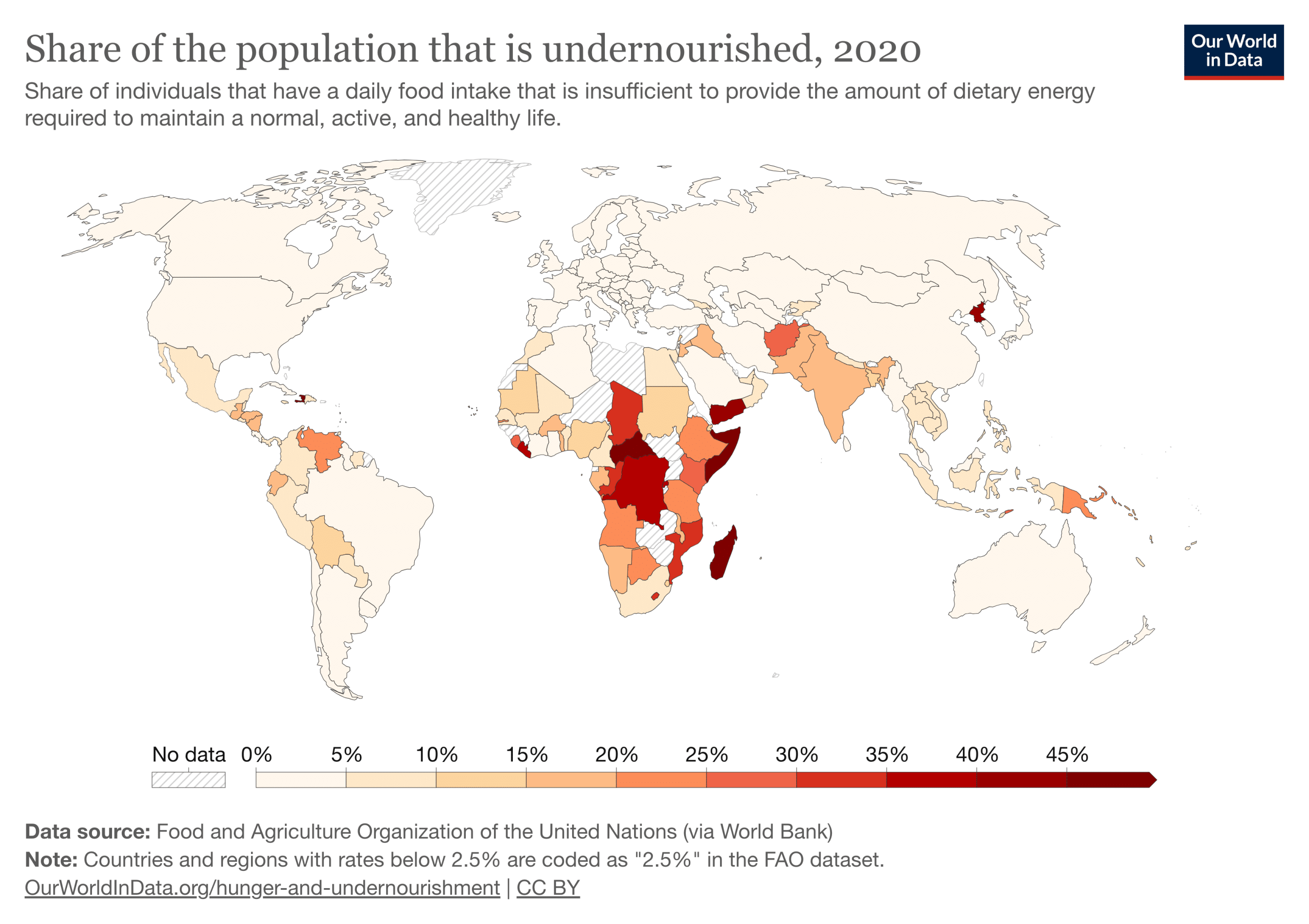

Having adequate access to food is one of the most basic and important human rights, and yet, hundreds of millions of people around the world suffer from starvation, with approximately 25,000 succumbing to hunger every day. An estimated 854 million people are also undernourished.

The COVID-19 pandemic has heavily compromised food security globally, increasing hunger levels by an estimated 118 million people worldwide in 2020, the most since 2006. Hunger kills more people than HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined, the vast majority of which live in developing countries. And it is these countries that are now experiencing the worst consequences of the current food crisis.

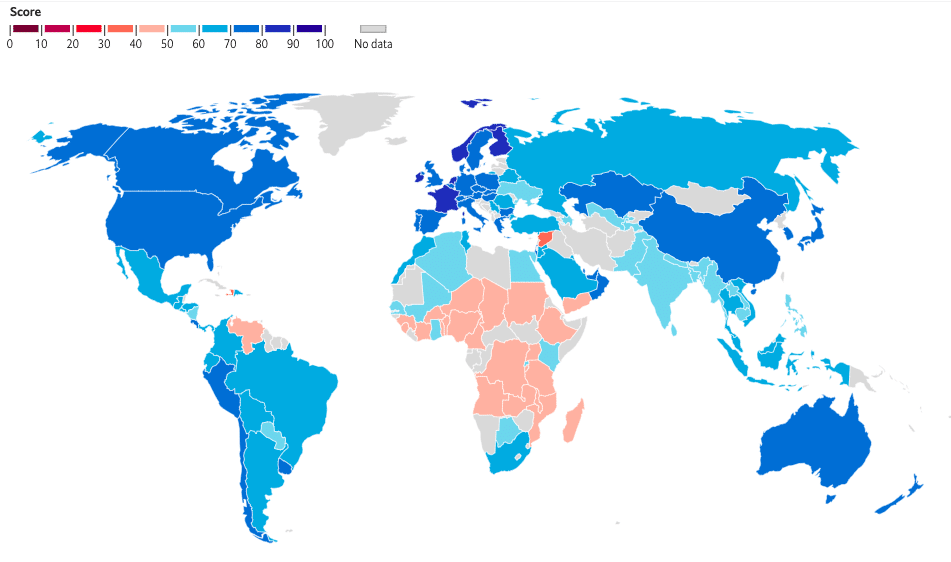

In 2012, The Economist first published the Global Food Security Index, an instrument that measures food security in 113 countries. Yearly rankings show this varies greatly around the world. Some regions are more prone to food insecurity due to a lack of fertile land as well as capital to procure sufficient food through the purchasing of imports. However, some external factors such as sudden armed conflicts like the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war or global health issues like the recent pandemic compromise food supplies in ‘safer’ countries as well.

According to the 2022 Index, Finland, Ireland, and Norway share the top rank with the overall GFS score in the range of 80 and 84 points on the index, proving that these countries all have sufficient and affordable food supplies and natural resources to support their population as well as adequate food safety net programmes. The seven worst performing countries in that year were all in Africa – with the exception of Syria and Haiti, the lowest and second-lowest in the rank, respectively – with scores ranging from 34 to 37 for their low availability and affordability of food supplies as well as very low quality and safety standards.

You might also like: How Wheat Shortage Is Sparking a Global Food Crisis

The world population is growing at a rate of about 1% each year, a significant decrease from the 2.2% growth from 50 years ago. Despite this, estimates predict that by 2050, it will increase by another two billion, bringing the total number of people living on Earth to nearly 10 billion. This rapid population growth can have devastating consequences on our planet by putting a strain on its resources, most notably on food supplies. The factors that connect population growth to food security are manifold and range from drastic changes in human diets to the ways in which we produce food. On the one hand, especially in richer countries, people have become wealthier and are eating more. On the other hand, they are opting for more resource-intensive and environmentally impactful food. However, as demand grows, resources decline. To meet the ever-increasing demand, food production had to be scaled up, though this has in turn pushed humanity to the brink of exceeding planetary boundaries. Today’s agricultural system is struggling to deliver enough food to meet that need.

Another huge problem with our current global food system is the amount of food waste it generates. Shockingly, even though demand for food is high, we still throw away about one-third of global supplies every year, equivalent to nearly 1.2 billion tonnes of food. Research suggests that if high-income countries reduced post-harvest waste by 50%, the number of undernourished people in poor countries could be reduced by up to 63 million. It becomes clear that simply reducing food waste could drastically improve global food security.

But problems related to our food system are just one of the factors impacting global food supplies. Food security and climate change are also deeply connected, with the latter being a threat multiplier for undernourished people and accounting for one of the biggest causes of food insecurity. Drivers of climate change such as biodiversity loss, increased pollution, and extreme weather-related disasters compromise agricultural production, significantly reducing the yields of major crops. Simultaneously, the overexploitation of land and the intensive use of fertilisers and pesticides required to meet the ever-rising food demand are destroying entire ecosystems, impacting species population, and compromising soil fertility, limiting the already restricted amount of food that we can grow. Evidence suggests that in just over 6 decades, over 35% of arable land has been degraded due to human-induced activities.

You might also like: The Growing Importance of Food and Water Security Amid the Ukraine-Russia War

What Happens When Food Security Is Compromised?

Population growth, improvement in incomes, and diversification of diets have steadily increased the demand for food. If we do not change fast enough, then global food security will be irreversibly compromised. And when this happens, it will lead to catastrophic consequences for societies around the world.

The most obvious effect is increased hunger rates and famine especially in developing countries as well as, in the most extreme case, a global food crisis. Children are expected to suffer the most from food scarcity, as undernourishment leaves them weak, vulnerable, and less able to fight common childhood diseases such as diarrhea and measles. Save the Children estimates that nearly 5.7 million children around the globe are on the brink of starvation.

When global food security is compromised, comes huge economic consequences. Produce scarcity would inevitably contribute to a huge rise in food prices. Simultaneously, undernourished people may experience feelings of stress and anxiety that could reduce their productivity, school performance, work participation, and even lead to job losses. A drastic reduction in households’ income paired with rising prices will also inevitably slow down the economy and create a dangerous loop, with even more unemployment and less economic power from governments to fight the food crisis. Furthermore, food scarcity often leads to political instability and internal as well as international conflicts, as wealthier countries exploit poorer ones in the race to secure already limited food supplies.

You might also like: 3 Biggest Threats to Global Food Security

Ensuring the Future of Food Security

The current global food crisis, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and now also threatened by the conflict in Ukraine, is a huge challenge that has affected countries around the world at very different rates. If we want to avoid the rolling back of developmental gains painfully won over the last century, avoid further mass impoverishment and global famine, we need to step up sustained international political commitment.

Crucial steps to ensure food security across the world will need to include a more effective distribution of food supplies and a drastic change in the food system as we know it. We can no longer produce food for economic profit. Our goal should be making sure no one goes hungry by decreasing demand in wealthier nations while increasing supply in developing countries. We also need to invest in more sustainable agricultural practices and new technologies and educate societies on the repercussions of food waste.

On a policy level, interventions such as better options for handling resource allocation, land use patterns, food trade, and the regulation of food prices, are urgently needed. The European Union recently proposed a €1.5 billion (USD$1.65 billion) funding package to shore up food security as a response to the sudden increase in food prices following the invasion of Ukraine. The money would be used to finance farmers and operations to free up 4 million hectares of fallow land for crops.

While this proposal offers hope that global food security can be restored before it is too late, we must look ahead and focus on strategies to prevent shortages in the first place. This, however, requires a drastic shift in our approach to food production and consumption.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us