The prospect of disaster is one of the few constants within nature’s unpredictable mutability, and one that Japan is all too familiar with. The island nation is acutely vulnerable to earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic activity, but this legendary association with disasters goes beyond the Ring of Fire as it is ranked 9th globally for exposure to natural hazards like landslides and typhoons. Japan has learned how to deftly navigate around the ghosts that have haunted its past, and it is assisting other countries in their journeys to confront rising climate challenges. Disasters can be a catalyst for a “reset” in global governance and Japan’s disaster diplomacy is a way to carve out niches in competing spheres of influence, especially in Southeast Asia. But Japan is no longer alone in this enterprise, having been joined by China who is keen to pursue its own agenda in the Asia-Pacific.

—

Taming the Tempest

Japan’s uneasy calm following the Second World War was punctuated by a series of climate-related shocks, the most devastating of which was the Ise Bay Typhoon of September 1959 that claimed 5,000 lives. The country’s ability to cope had been seriously hampered by its still-recovering economy, and the significant losses were the impetus for the consolidation of a modern disaster prevention system. The Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act of 1961 emerged as the definitive template for prevention, response, and recovery policies. The legislation’s key components include the creation of disaster management councils, the articulation of a disaster prevention plan that is reviewed yearly to incorporate the latest research developments and analysis of existing emergency measures, and the delineation of financial assistance obligations. The dimensions of Japan’s “countermeasures” generally include studying the technical aspects of disaster prevention, reinforcing the disaster prevention system’s mechanisms, enhancing infrastructure resilience, emergency response and recovery efforts, and improving communication channels.

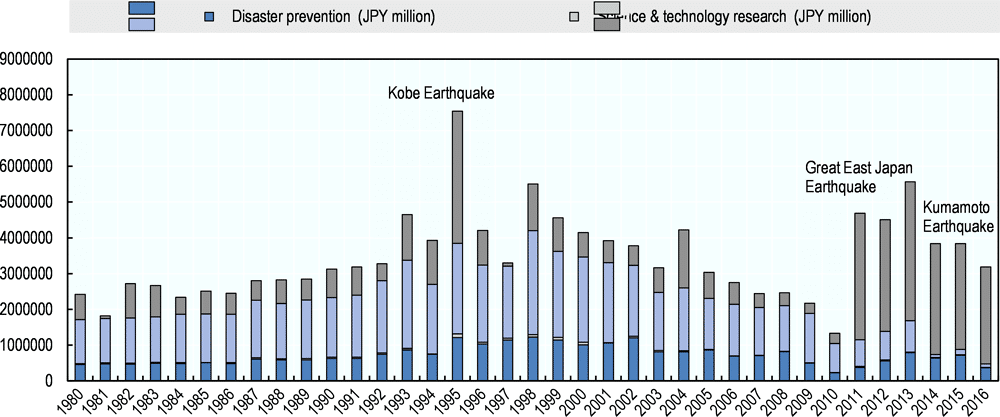

Japan’s strategy does not view disaster risk reduction (DRR) as an inconvenient expenditure that detracts from the government’s core responsibilities. It is an investment in the nation’s future security and prosperity, and this proactive outlook of combining both structural and “softer” non-structural prevention measures has suffused the realities of everyday life.

It is also a collaborative exercise integrating the perspectives of multiple stakeholder groups to scale up efficiency and account for capacity and resource gaps. The government (at the national, prefectural, and municipal level) is at the apex of this hierarchy, coordinating the overall implementation of disaster management plans. Public and private entities are fundamental to the provision and facilitation of activities and services forming the government’s operations. Participation in the Central Disaster Management Council is mandated for public institutions like the Bank of Japan and electricity utilities, who are also required to devise their own DRR schemes. Certain private corporations even have enhanced responsibilities in this process, ranging from active involvement in evacuation drills to the ideation of products with amplified DRR capabilities. Research and academic organisations are continuously fine-tuning the minutiae of disaster prevention, like building regulations and observation systems, and diffusing the ever-expanding pool of knowledge. Mass media is an integral link in this chain as well, relaying critical information and warnings, and effectively rooting the unrelenting promise of natural threats into the national consciousness. Finally, beyond the elegantly engineered defences lies Japan’s greatest asset: communities that have internalised an ethos of initiative and resilience, ready to act when protective measures fail.

The Politics of Japan’s Disaster Diplomacy and International Relief

Disasters can be a catalyst for a “reset” in global governance, presenting opportunities for countries to elevate, or even entirely reimagine, their place in the world by following a humanitarian agenda that allows them to cast “new alliances” over “ancient grievances”. Japan has become a prominent voice in the disaster landscape due to its primordial entanglement with calamities, and its exporting of the lessons built from that experience is one of its most consequential contributions to the 21st century world order.

The decision to go outside its borders is based in part on a sombre reading of its history and uncertainty over its geopolitical stability. Disaster assistance is embedded into the country’s Official Development Assistance (ODA), which is the flow of aid into developing countries. For reference, Japan provided USD$16.3 billion in 2020, with fiscal year 2021 (April 2021 to March 2022) estimating at 7% higher than 2020’s numbers. ODA policy, administered through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), had its genesis in the country’s postwar ascent and reentry into the global stage. The policy is predicated on Japan’s distinction as both “recipient and donor” and has assumed the role of “reputation-mender and builder”, enabling the nation to pursue reconstruction and reconciliation with the victims, particularly in Southeast Asia, of its dark imperial past.

‘Disaster diplomacy’ is also a vehicle for assuaging the tensions surfaced by Japan’s juxtaposition between China and South Korea. Japan’s waning influence is eclipsed by China, which is hungering for maritime and terrestrial dominance. While South Korea remains more in the periphery, lingering bitterness stemming from World War II has steeped what is already a delicate relationship that is further fraying at the seams over recent territorial disputes. Japan’s interdependence on its neighbours makes its environmental vulnerability an economic and national security weakness.

By the same token, strategically addressing extreme climatic events abroad by sharing its deep, nearly innate, expertise can allow Japan to strengthen its role in and reorient the trajectory of its impact on the region. It is ironic that the military, one of the thorns in Japan’s legacy, is extending an olive branch to materialise this dream. The 1987 enactment and 1992 amendment of the Japan Disaster Relief (JDR) team’s law, establishes a system for responding to overseas emergencies, and authorises the routine mobilisation of the Self-Defence Forces in Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HA/DR) operations.

These missions are one facet of a nexus of projects that reinforces Japan’s image and affirms its commitment to the greater international community. This assistance spans the entire disaster management lifecycle and has been embedded into policy frameworks like the National Security Strategy. Ensuring a “fast start” is paramount for success in disaster prevention and response, and the Japanese government makes use of a variety of mediums and partners to guide that process along. One such collaboration is a 2014 programme launched jointly with the World Bank that supports developing countries with an array of financial and technical tools for the “mainstreaming” of disaster risk management. Japan is also pioneering the setting of universal roadmaps like the Hyogo and Sendai Frameworks, named after the cities that hosted the United Nations World Conferences on Disaster Risk Reduction in 2005 and 2015, respectively. The former conference, the first with such a plan of its kind, outlined five priorities to significantly alleviate disaster impacts by 2015. It was succeeded by the Sendai Framework which defined seven targets to be achieved by 2030. Among these targets are considerations for accelerating international cooperation to enable developing countries to see through the implementation of their national action plans.

You might also like: Is Climate Change Reshaping The Future of International Diplomacy?

A New Frontier

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs identified “similar climatic, topographic, and geographical conditions” as almost prerequisites for successful international cooperation in DRR. Combined with intersecting histories and concerns about the regional balance of power, it is unsurprising that Southeast Asia is the prime object of Japan’s attention in this domain.

Tokyo has a “new appraisal of Southeast Asia in [its] strategic calculations” to maintain its vision for a stable Indo-Pacific, one in which China’s aggressive advances are buffered by Japan’s more pacifist investments. This wariness of Beijing transcends Japan’s sensitivities about the integrity of its position. It is also reflected, albeit not as heightened, in the sentiments of the countries in the immediate vicinity. For example, in its November 2021 Disaster Management Reference Handbook, the Philippines explicitly underscored China’s construction of military installations on artificial islands in “disputed waters over rich natural resources such as untapped oil, natural gas, and fishing areas” as a source of anxiety. If China were to apply more pressure here, Japan can stand as a counter to this shifting of the equilibrium, and this dynamic will not go unnoticed.

Even against the narrative of wartime occupation, Southeast Asia has welcomed sustained engagement with Japan because the relationship has awarded the former “contemporary security”, a reprieve from the political and social turbulence of the Cold War. While China’s meteoric growth has afforded it the luxury to pledge increasingly higher amounts of aid, Japan has been a reliable partner throughout the decades. There is a marked difference between pledging and delivering foreign aid. China’s pledge to East Asia for 2001 to 2011 was US$107 billion; of that amount, only $5.9 billion was actually delivered, with $5.8 billion going to Southeast Asia. On the other hand, Japan pledged $12.7 billion for that same period, delivering $12.7 billion and allocating $8 billion to Southeast Asia. Although “Beijing…excelled at making promises”, Tokyo has kept them, allowing it to be “far better at…exerting its influence”. It is also necessary to distinguish between the two powers’ tangible contributions. Japan’s approach makes use of both hard and soft infrastructure, neatly packaged as “quality infrastructure”, which includes disaster risk mitigation, whereas China appears anchored to hard infrastructure.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is instrumental for facilitating the dialogue with Japan. Disaster management has recently come to the fore to join the bloc’s traditional areas of focus like maritime security and trade, and a current priority is exploring the “effective use of science and technology”. Japan’s support to the ASEAN network is expansive, covering financial assistance to the supplying of information and technology systems. This alliance with ASEAN is painted with a degree of reciprocity. Member states provide Japan with vital sources of energy, as part of a bilateral trade stream worth over $200 billion annually. They also spared no time in responding to Japan’s greatest hour of need, dispatching elite medical and search and rescue (SAR) teams and donating millions in financial assistance.

Through various levels of cooperation, Southeast Asia has internalised a number of principles for bolstering its resilience. One is enhancing risk identification and analysis. Japan has supported this venture from the beginning because it knows the merit of precision in forecasting. It recently provided two weather radar systems to the Vietnam Meteorological and Hydrological Administration to “help make weather guidance more quantitative and reliable” and enable the country to glean accurate insights from the data. Another lesson is increasing DRR investment across a wide swath of sectors. After the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake, JICA played an indispensable role in reconstruction by establishing “application and certification procedures, carr[ying] out capacity training to officers in charge, while providing technical advice” on how to build fortified structures. Finally, there is recognition that disaster management is an iterative process that is forged through the cycle of sharing. JICA has provided $3 billion to the Philippines since 1979, with this support helping to bring a central concept of the latter’s strategy, that of DRR localisation, to fruition. Filipino officials participate in disaster management training sessions held in Japan to absorb “experiences, technology and innovation, and…good practices.” These trainings also serve as a conduit for knowledge and capacity development as they demonstrate the efficacy of Japan’s structural and non-structural measures.

Southeast Asia is at the precipice of a dangerous free fall, necessitating the urgent advancement of its capacity to mitigate climate emergencies. It is where “high exposure meets high vulnerability” and a growing urban population is increasingly put in the direct line of nature’s wrath. Weather-related events displaced 54.5 million people between 2008 and 2018, and this temporary migration, with the potential to become permanent, is a potent threat to local economies and long-term stability. Superstorms and rising sea levels, poised to affect more than three fourths of Southeast Asians by the end of the century, will exacerbate existing food and water insecurity; these combined impacts also have serious implications for the progress made by these countries in improving standards of living.

The Other Player in Global Governance

China’s disaster diplomacy, like Japan’s, is a function of its self-perception and assessment of rival powers. It is a vessel for the manifestation of lofty foreign policy goals, most of which are related to China’s place in the competition for global governance. Its 1999 Going Global Strategy invigorated a “resource push” that has seen the world transformed “so rapidly…with such single-minded determination”. Initiatives like the Belt and Road and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road will bring 64% of the world’s population and 30% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) under China’s yoke. Therefore, responding to overseas natural disasters can work in the country’s favour to cultivate new symbiotic alliances and protect existing assets in vulnerable localities.

Though ambitious, China’s international disaster management cooperation is a nascent endeavour. It has been “seeking a benign and responsible image” in the last 20 years, but honing in on crises induced by natural hazards has only recently become a keystone policy. Unlike the Japanese government, which coalesces a broad range of actors, China prefers “government-to-government channels” for distributing aid because of its “state-centric worldview” and hesitations about the activities of non-governmental organisations. This emphasis on bilateralism can become tricky for China because it hints at ulterior motives, which might make countries on the other end less receptive to assistance.

Nevertheless, China is making considerable strides in this undertaking. The restructuring of the government in 2018 saw the creation of the Ministry of Emergency Management and China International Development Cooperation Agency, intended to enhance its array of DRR-related abilities. The partnership with ASEAN is an important forum for allowing China to have a discernible presence in the region. While it has signed cooperative arrangements with ASEAN, bureaucratic inertia has affected the rate at which funds are disbursed and projects initiated. For success in this space, it needs to ensure that it has the tools to effectively use disaster diplomacy. Increased connectivity, both within and outside the nation, will help gauge to what extent China’s aid addresses the needs of the recipient. Again, the softer side of mitigation shows up in the conversation as China can facilitate the smoother application of its projects by familiarising itself with the particularities of the host countries.

For all of their differences, Japan and China can find common ground in the use of their militaries in HA/DR operations. Since 2004, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has figured into “non-traditional security paradigms” which permitted the reformulation of its capacity and capabilities to respond to disasters. There is a unique opportunity for military cooperation to supersede the long-simmering “misunderstanding and miscalculation” between these two neighbours, which can pave the way for Asia to find some semblance of peace.

Featured image by: Toshiharu Kato / Japanese Red Cross Society (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)