Diplomacy is complicated. It can be much easier for countries with competing economic, political or military interests to disagree with each other rather than find a mutually agreeable solution. If diplomatic action and peacemaking require one actor to compromise without receiving any notable gains, they will be unlikely to do so. This happens with most topics of diplomatic discussion, but perhaps climate change, a global challenge that requires coordinated efforts to solve, can stand out among the myriad of endless interstate debate to be an issue of common interest. Could the environmental crisis be one of such massive proportions that it transcends political squabbles, and even become a tool for international peacebuilding?

—

In June 2021, US President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin walked away from a highly publicised summit without having arrived at any real resolutions to the frosty relationship between their two countries. But then, one month later, US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry travelled to Russia and held a successful meeting with Putin over a shared interest in mitigating climate change.

In March, American and Chinese representatives criticised each other relentlessly over perceived human rights abuses, intellectual property theft and more at a dramatic bilateral conference between top diplomats in Alaska. Just a few weeks later, Kerry met with China’s Special Envoy for Climate Change Xie Zhenhua at a summit that concluded with a joint statement between the US and China to cooperate with each other in addressing the climate crisis.

These two similar stories are emblematic of a trend that has begun to repeat itself more and more as governments begin to acknowledge the political reality and urgency of dealing with climate change. Countries can be at each other’s throats over virtually anything, but tackling climate change is different. Buildup of atmospheric carbon, warming temperatures and extreme weather events do not care about borders. Even if one country is successful in reducing its own emissions, it means little if other nations halfway across the world continue to burn fossil fuels and generate greenhouse gases.

This is why global climate leadership doesn’t only mean having hegemonic control over technology and resources, it also means being able to coordinate transnational efforts to reduce emissions, and ensuring that other nations are doing their part. Unlike historical races for technological or military supremacy, focus on domestic action and competitive attitudes towards other countries does nothing to fix the ecological crisis we have unleashed upon the world. Climate diplomacy is therefore emerging to be a crucial asset for nations wishing to achieve their own climate goals, while also leading others to do the same.

A Stark Reality

Climate diplomacy, and an interest in pursuing it, did not emerge from a vacuum. As the impacts of climate change become more apparent, it becomes increasingly difficult for leaders to deny the urgency of the situation, behaviour that has been worryingly common up to this point.

“Maybe climate change is not so bad in such a cold country as ours? 2-3 degrees wouldn’t hurt, we’ll spend less on fur coats, and the grain harvest would go up.”

Vladimir Putin said these infamous words in 2003, when asked what he thought of the Kyoto Protocol and the global call to action to address climate change. It is a statement that embodies Russia’s historical aversion to climate action, filling the role of a country that dragged its heels for years before ratifying the Paris Agreement, and has long been viewed as an obstacle of sorts in international mitigation.

But the time for Putin’s skepticism and misguided belief that climate change could be good for Russia has long, long passed. Unprecedentedly severe Siberian wildfires, melting permafrost causing debilitating infrastructural damages and heat waves that have killed tens of thousands of people are making climate change an incontrovertible truth, even for Putin.

The reality of climate change impacts on home soil is what coerced Putin to begrudgingly ratify the Paris Agreement in 2019. And it is what has pushed him to join other world leaders in pursuing coordinated efforts, to the point where he thinks that “the climate problem is one of the areas where Russia and the United States have common interests and similar approaches,” as he told John Kerry upon the latter’s recent visit to Moscow.

Image 1: John Kerry, US Presidential Envoy for Climate (right), met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in July 2021 to discuss coordinated efforts to tackle climate change.

The same scenario is playing out across most of the globe. As the impacts of climate change become ever more apparent and incur higher and higher costs, governments are increasingly obligated to address it. And while describing the problem is not the same as resolving it, the fact that leaders are acknowledging the crisis is a consequential if small step forward.

And because governments are realising that addressing climate change will require coordinated efforts, leaders are finally motivated to sit down with their counterparts to discuss tackling a common goal, when they might never have done so otherwise. This lucidity was on display at the April 2021 Leaders’ Summit on Climate, when Biden virtually hosted traditional rivals including Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping to discuss transnational commitments to address climate change.

As the worsening impacts of climate change bring more and more powerful individuals to the table, the opportunities are rife to leverage this communication. Chinese and American leaders, for instance, attack each other on virtually everything from mutual accusations of human rights abuses to cybersecurity concerns to contesting territorial claims. But climate is proving to be a surprisingly durable subject of cross-Pacific discussion, bringing the leaders of the world’s two largest superpowers together when seemingly all else divides them.

Climate change is the only thing that perennial rivals like China and the US, or Russia and the US, can agree upon, which speaks volumes to the seriousness of the crisis. So how do we leverage this, and what could the long-term implications of climate diplomacy be for the world?

You might also like: Why Not All Climate Pledges Are Created Equal

Environmental Peacebuilding

Much is being written about how climate change will impact the national security of states worldwide, by creating conditions of insecurity and even fomenting conflict. Climate change impacts can be felt all across the globe, including droughts, floods and extreme storms, can severely damage infrastructure and destabilise economic production. This can lead to a loss of livelihoods in virtually every sector, contributing to heightened resource scarcity, economic insecurity and social unrest within a country. All these factors combined can conceivably bring about episodes of violence and militaristic conflict.

There is compelling evidence that climate change-induced droughts were contributing factors in the events leading up to the Syrian Civil War in 2011, and more instances of both domestic and intrastate conflict in several African and Southeast Asian countries have been at least partially attributed to climate change.

But if climate change presents a risk to the security status of nations, then addressing the crisis can also create opportunities to mitigate conflicts entirely. If environmental degradation and resource scarcity are partially to blame for instances of conflict, then tackling those environmental problems can build a more ecologically sustainable society, while also supporting critical conflict resolution and peacebuilding projects.

Environmental peacebuilding can be done by investing in preserving livelihoods, strengthening public institutions and fostering cooperation and solidarity within a conflict-affected country. While most peacebuilding initiatives target economic development goals or building better governance, environmental peacebuilding specifically addresses the environmental sources of conflict. Successful implementations of environmental peacebuilding include building more inclusive and transparent environmental protection institutions in Ghana and Sierra Leone, or implementing sustainable resource management initiatives in Timor-Leste.

Image 2: Members of the Indonesian Formed Police Unit working with the UN planting trees outside of Darfur, Sudan; UN Photo/Albert González Farran.

By integrating conflict resolution or prevention with resource management, projects such as these have been able to support both peacebuilding and ecological conservation efforts. They show that, while climate change can play a role in conflict breaking out, awareness of environmental degradation in a restless area can help policymakers pinpoint at least some of the root causes behind instability, and address them accordingly. It is why some actors, including the EU, have directly incorporated climate security into their diplomatic initiatives.

The value of addressing climate change in increasing global prosperity and engaging in environmental peacebuilding is only part of the reason why states are growingly inclined to participate in climate diplomacy. Tackling climate change on a global scale, and making a good public show about it, is also in line with what voters back home are largely clamouring for.

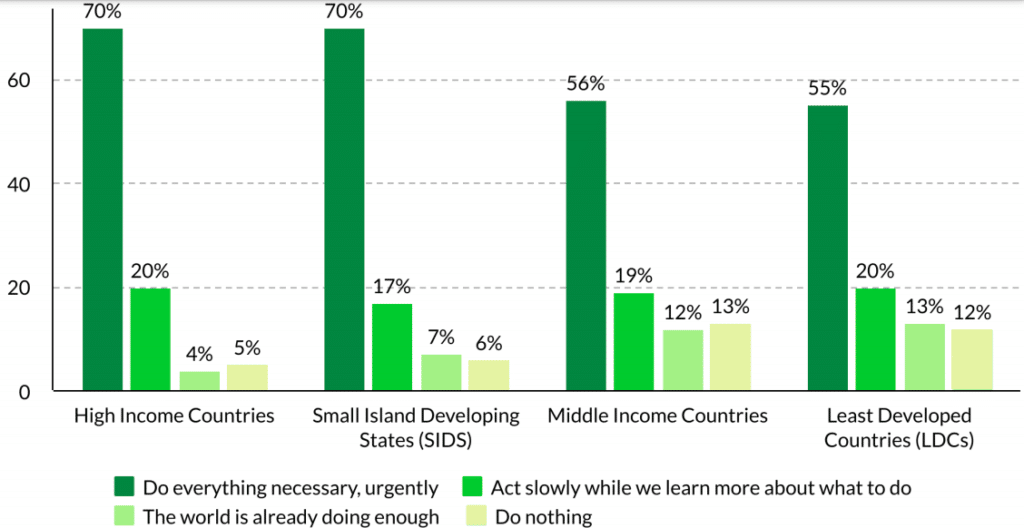

In January 2021, the UN released a landmark global survey, a climate change polling initiative spread out over 50 countries covering 56% of the world’s population, the largest such survey on climate change ever taken. The report found that 64% of the world considered climate change to constitute a global emergency, with only 11% thinking we should not be doing anything to address the crisis.

When such a large majority of constituents pleads for ambitious actions to be taken, it is easier for democratically elected governments to set aside differences and improve diplomatic ties. In the past, crises like nuclear war, militaristic uprisings or competition between superpowers dominated international relations. And with these threats competitiveness and antagonism may have been a favourable strategy. But as the impacts of climate change become ever more apparent, leaders have an opportunity to strengthen their rapports and establish more fruitful relationships overseas, while also improving their image back home.

Figure 1: Urgency of response among people who believe in the climate emergency, arranged by country group; UN Development Programme; 2021.

So even though politicians and administrations might engage in climate diplomacy for somewhat self-serving reasons, it is certainly encouraging that leaders are willing to sit down with each other, especially when there is no indication that they would do so otherwise. But global summits and diplomatic conversations can only take us so far. What is missing for climate diplomacy to really instigate some tangible changes?

From Words To Action

The promise of strengthened diplomacy comes with a caveat, of course. All the summits and conferences in the world do little good if rhetoric and agreements are not matched by action. Brazil, for instance, had a buoyant performance at the Leaders’ Summit in April, with President Jair Bolsonaro promising to increase spending to fight deforestation. But the very next day, the government cut funding for its environmental conservation program by 24%.

The same is true of climate diplomacy and peacebuilding. Even if climate change is enough to bring leaders to the table, action needs to match ambition.

The pledge made by Russia and the US to work together on climate is promising, but so far, Russia’s climate policy remains insufficient in meeting the Paris Agreement targets, and it does not appear that substantial change will occur in the near future. What this tells us is that, while it is encouraging to see nations come together to discuss a problem that requires cooperative action, there is still a place, a necessity even, for a degree of unilateralism.

For countries high on rhetoric but low on actionable policy, coercive and enforceable mechanisms need to be employed that can keep governments accountable for their emissions and environmental impact. And when governments will not implement these policies domestically themselves, it helps to have an external actor help move things along.

Carbon border adjustment taxes are one-sided mechanisms that price imports from countries that continue to employ carbon-intensive practices, usually in manufacturing or shipping. What these mechanisms do is essentially place a price on carbon when prices were not applied at the source of emissions. These pricing mechanisms often provide a double benefit for the countries that impose them by protecting the competitiveness of domestic industry while also accomplishing environmental goals.

Carbon border taxes are beginning to gain traction, with legislatures in the UK and US both actively considering them. The EU has recently taken the major step of being the first political entity to announce concrete plans for a carbon border tax, which will be implemented beginning in 2026. Putin, unsurprisingly, is opposed to this.

A carbon border tax places non-committal countries like Russia in a difficult position. Even if Putin does not think that such radical action should be taken to address climate change, he recognises that the world is trending towards believing the opposite.

“I don’t think Russia suddenly discovered it had a huge interest in the fate of the planet, but it speaks to the fact that climate change has become a real, concrete geopolitical issue,” Lola Vallejo, climate program director at the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations, recently told CNN.

Geopolitics, overwhelming public opinion and pure pragmatism are bringing countries together to discuss climate change, but both diplomacy and unilateral measures have to be employed simultaneously to push the most desperately needed, and sometimes difficult, policies over the line. A pessimistic view would be that nations will see and understand the threat of climate change, and still devolve into time-wasting competitiveness, but this somewhat misses the point. True, competition is less ideal than cooperation, but if harnessed correctly, competing great powers can change the world for the better.

A carbon border tax could spur innovation and development of new green technologies across the world, and may also potentially jolt world trade to never-before-seen levels of profitability. And as more and more countries get drawn into global discussions on climate diplomacy and potential solutions, the opportunities for environmental peacebuilding and conflict resolution can only grow.

People are not always great at working together, and the question as to whether or not climate diplomacy actually works can in many ways boil down to human nature. As wildfires burn and cities flood, it becomes more and more nonsensical, absurd even, that the urgency around climate change is not yet palpable. It could be in our nature, somehow, that even for those who are emotionally or professionally invested in climate change, the immensity of the crisis becomes too much to internalise, too much for any one person to handle.

But that is exactly why the climate crisis requires cooperation to resolve. Just like no single person can fix climate change, no single government could hope to do so either. The good news is that it appears we are beginning to realise that, we are starting to work together and listen to each other more in the face of a truly monumental challenge. The hope is that we might soon reach a tipping point, wherein the evidence and public outcry has piled so high that governments no longer have any reasonable explanation to not engage in a form of diplomacy to address climate change, and cannot criticise others for acting unilaterally either.

Featured image by: Wikimedia Commons