Once relegated to the fringes of domestic and international politics, green parties are now firmly entering the political mainstream, taking on increasingly powerful and influential positions in policymaking and statecraft. Rooted in a history of social activism and grassroots movements, green parties have never been this popular, but questions abound over what their newfound prominence really means. Is the global green party movement a monolith? What divides different green political parties? And could their growth entail a radical change in how governments value environmental policy?

—

The Green Party and the Upcoming German Elections

On September 26th, citizens of Germany will go to the polls and vote in the country’s next federal parliament and its chancellor, the German head of government. Incumbent chancellor Angela Merkel will not be running in this election, marking the end to her 16-year tenure and paving the way for another party to take the majority.

Polls show that the race is still on between Merkel’s conservative Christian Democrats party, the centre-left Social Democrats and the impressively ascendant Greens. According to The Guardian’s poll watcher, the Greens enjoyed a 25.6% support amongst voters last spring, higher than any other party. While they are no longer in the lead of the race, the young party is in contention for a strong showing at the end of September, and is virtually guaranteed to play a significant role in the next government of the world’s fourth largest economy.

The German Greens’ remarkable success this year comes as little surprise to observers, as the party has been impressing for years. When the party first entered politics in 1998, they only garnered 6.7% of the vote in that year’s election, despite a coalition agreement with the more established Social Democrats. Now, the Greens boast support at the polls consistently over 20%, and have enjoyed a comfortable presence in Germany’s parliament for years. The party is also a founding and leading member of the European Green Party, a coalition of European political parties representing and supporting green political priorities, and are considered crucial in popularising green politics in western Europe.

The fact that a green party could conceivably become governor of Europe’s largest economy is indicative of how the global green party movement has grown in recent years. The popularity of green parties will hold implications for countries’ response to the environmental crisis and their economic policy, and may even help normalise the kind of radical but necessary action to tackle climate change.

Green parties are not all created equal, but they do tend to be united by a common goal to advocate for environmental protection. One-issue politicians and parties tend to enjoy certain advantages over more diversified contenders, but only if that one issue appeals to the general public. The rise in popularity of green parties is demonstrative of several trends, most notably, increasing public disappointment with governments’ inaction in the face of climate change. Moving forward, the obvious question is whether or not green parties are being genuine or realistic, and even if they are, will it be enough?

From Activists to Green Party Ministers

Green parties, and green politics in general, have been around for at least 40 years in the West, and their current appeal is a definite departure from the movement’s counterculture roots.

Green politics first emerged as a concern within the student activist movements that roiled the Western world in the mid-to-late 1960s. The ‘New Left’, as it was known, aimed to mobilise more progressive public opinion on issues such as civil rights, poverty, war and the environment. Major movements swept over the US, Italy and France, to name a few, and fundamentally changed the scope of left-wing politics.

The motivations behind the 1960s student protests were different from country to country, but all were generally rooted in an extreme dissatisfaction with industrial civilisation and envisioned a radically different world in which humans could live harmoniously with nature. These movements lay the foundation for a new generation of educated, progressive and at the time radical political organisers to emerge, many of which would go on to lead the first green parties.

The earliest green parties were founded in the 1970s, with the United Tasmania Group in Australia, the PEOPLE Party in the UK, and the Values Party in New Zealand being some of the first to actually contest elections. The German Green Party, or West German Green Party as it was known at the time, was the first of its kind to truly enter the political mainstream in the 1983 elections, overcoming a 5% vote hurdle and earning seats in a government’s legislature for the first time. Since then, green parties have undergone a transition from activists to lawmakers, firmly entering the political mainstream in several countries.

Outside of Europe, green parties are also beginning to make a splash. Even in a country like the US, with a notoriously impregnable two-party system that does not enable a parliamentary structure to favour the chances of smaller parties, members of the US Green Party have won hundreds of local and state elections.

In their early days, when green parties still channeled activism, platforms were as diverse and disparate as they come, with some parties being ardently opposed to nuclear weapons and energy, and others much more focused on stamping out consumerism, greed and endless economic growth. The divergence of priorities between green parties, and sometimes even within the same parties, often led to infighting and a lack of cohesion.

But now, green parties worldwide are more unified than ever. And that unity has translated to unprecedented success as their political priorities become more universal. Green parties’ evolution from their activist roots to becoming more or less a part of the political establishment has come somewhat at the cost of their counterculture origins. But this is not because the parties themselves have changed their tune, it is because the songs they are singing have entered the mainstream as well.

Unity in the Face of Disaster

Two thirds of Americans think that the government should be doing more to fight climate change. 63% of UK voters believe that climate change poses a direct threat to the country. 93% of EU citizens think that climate change is a serious threat, and 90% believe that the EU should do everything in its power to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

The public outcry for more ambitious climate action is behind the rise of green parties and politics, and this growing public concern is in turn caused by climate change impacts becoming increasingly serious and damaging.

Green parties have always been aligned with a common goal of establishing a more harmonious human relationship with nature, but have historically been very much at internal odds with each other on how exactly to do this.

One of the biggest points of contention between green politicians in the past, for instance, has been nuclear energy: whether it is necessary as a transitional energy source or a pointless risk. But as the Earth becomes progressively warmer, and phasing out fossil fuels has shifted to a priority, some parties have softened their stance on nuclear substantially. Finland’s Green Party did exactly this in 2020, publicly backing the use of small nuclear modular reactors while remaining opposed to new large nuclear power plants, directly citing the urgency of reaching carbon neutrality as a justification for their policy reversal.

Other points of debate still exist. Most factions advocate for green growth, the belief that sustainable solutions and lifestyles can still operate within the confines of capitalist markets through the use of new technologies such as carbon capture or geoengineering. Others, such as the more radical wings of the New Zealand or Irish Greens, take a more hardline approach, calling for “degrowth” policies to rapidly draw down economic activity and shift away from market-based approaches and consumerism altogether.

Overall, however, differing factions in green parties have largely decided to reconcile their opinions to create a more unified front. The German Greens have done exactly this, proposing a coherent policy platform that includes decarbonising Germany’s auto manufacturing sector, phasing out all coal use by 2030, raising Germany’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from 55% to 70% by 2030 and investing €500 billion over the next decade on the “socio-ecological transformation” of the German economy.

Embed from Getty Images

Annalena Baerbock, the German Green Party’s pick for chancellor in the 2021 elections/Getty Images.

A political party unsure of its identity or of its appeal would not make such promises. The German Greens’ popularity might be benefitting from the country’s generally progressive society and public concern towards climate change (which is high even by European standards), but the same trend is happening worldwide. As climate change continues to touch each and every one of our lives in increasingly consequential ways, the policies and stances advocated for by green parties become much less radical and much more appealing.

Youth climate activism such as the Fridays for Future campaign started by Greta Thunberg, which drew almost 8 million strikers in 2019, have gotten substantial media attention. Some youth movements have even been successful in pushing governments to substantially amend their policies. But it’s not only the youth. Older people and retirees, sometimes known as ‘grey greens,’ have participated in protests and climate activism, often facing arrest and putting their bodies on the line.

In early September 2021, the Washington Post reported on the many seniors protesting in the streets of London’s financial district, who had joined up with the activist group Extinction Rebellion to decry the ties between financial groups and the fossil fuel industry. Charmian Kenner, an energised 67-year old ex-academic, told the Post: “I’d do anything to protect my grandchildren. I won’t live long enough to know whether it worked or not for them, but I’m here, doing this.”

The positions championed by green parties are broadly appealing, and not only to young people. As the world comes to grips with climate change’s urgent realities, what is missing for green politics to become not only mainstream, but a priority for legislators?

What are Green Parties Missing?

While green parties and politics have made substantial strides forward in recent years, there remains work to be done.

In Germany, despite their strong start, the Greens have fallen behind in the race somewhat. The Greens’ slide down the polls is largely due to the numerous attacks being levelled at the party’s pick for chancellor to succeed Angela Merkel, where 40-year-old Annalena Baerbock has been lambasted with accusations of everything from plagiarising content for her book to inconsistencies on how she declared tax on her Christmas bonuses.

Merkel is definitely a tough act to follow, and personal attacks in tightly-contested elections are to be expected, but the relative inexperience of Baerbock and her party have put both at a disadvantage in the final months of the election.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in the aftermath of the devastating floods that literally uprooted entire towns in July 2021, causing more than 180 deaths in western Germany. What should have been a galvanising political moment for the Greens, given that the floods were in part caused by climate change-induced heavy rainfall, became a missed opportunity, as the catastrophe did surprisingly little to shake up a race that was already slipping away from Baerbock’s party.

The same is true for other green parties around the world. When coming up against parties that have been in control of the political establishment for decades, or even generations in some cases, a lack of experience and good old-fashioned bureaucratic staticity can make it difficult for outsiders such as greens to break through.

This is why green parties’ general willingness to compromise and strike deals is a huge benefit. In the US, while the Green Party has been successful at local levels, green politicians still have little chance of making it into any federal legislature or executive office. But Democrats, especially members of the party’s more progressive left-wing branch such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders, have gone to great lengths to champion and integrate policy proposals of the Green Party, such as the Green New Deal.

Governing, of course, is not only about protecting the environment and decarbonisation. If in power, green parties will also have to formalise their foreign policy stances, which can at times be infinitely more complex than domestic affairs, especially considering the concurrent popularity rise of populist and isolationist right-wing competitors. In foreign policy, green parties, even those in wealthy and progressive western European countries, might have to adopt more centrist policies.

While green parties in general tend to be pacifist and opposed to foreign interventions or militarisation, the German Greens have been more pragmatic. The party has approved a programme that describes the NATO alliance as ‘indispensable,’ and has consistently pushed for shared foreign policy objectives with the EU. Green politics in general are incompatible with a militarised and competitive world, and require cooperation between nations to meet shared climate goals. Green parties have to understand how to reconcile this need with the realities of a diplomatic world that is still hyper-competitive, at times distrustful and still reliant on military alliances.

Green foreign policy objectives might also clash in possible coalition governments. In Germany, for instance, the Greens have taken more critical and hardline stances on relations with rivals China and Russia than any other party. Should the Greens eventually end up in a powerful position within a coalition government, this could potentially sow disagreements in Germany’s foreign policy planning.

Can Green Parties Become Global?

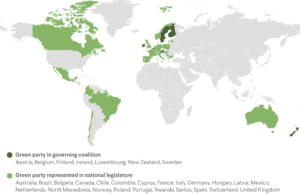

A final, but extremely important, latency within global green parties is their global distribution, or rather the lack thereof. Green parties might be on the rise in advanced and democratic economies in Western Europe and North America, but are nowhere near as popular in the rest of the world. Green politics have decidedly become euro-centric, in that they have not been adapted well enough to cultural and political conditions outside of a few mature economies, mainly in the western world.

Countries where green parties hold power. Green parties have very little representation in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and only a few Western and Northern European countries have Green Parties represented within governing coalitions; Council on Foreign Relations; 2021.

The only continent outside of Europe and North America where green party members have been able to enter local or national legislatures in any meaningful way has been Latin America, where green parties have had some minor success in capturing legislative seats in Mexico, Brazil and Colombia. But the Latin American green parties, dogged by institutionalised corruption and a generally conservative political culture, are still struggling to find their identity.

In Brazil, for instance, green politics are split between the centre-left Brazilian Green Party or Partido Verde, and the far-right religiously conservative Patriota Party, formerly known as the National Ecological Party. Current President Jair Bolsonaro, the most passive world leader on climate change to say the least, is said to be considering switching to the Patriota Party ahead of a possible run in the 2022 elections. Meanwhile, Mexico’s green party, known as PVEM, has been accused of putting pragmatism ahead of ideology, and the European Green Party in fact no longer recognises it as a green party in response to PVEM’s extremely conservative positions on the death penalty and same-sex marriage.

When you look at Africa or Asia, green parties are virtually nonexistent. In Africa, pan-continental environmental activism, such as the Green Belt Movement to counter deforestation founded by Kenyan Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Muta Maathai, has somewhat raised the profile of green politics, but has so far not translated into any notable gains for African green parties. This is in spite of the fact that many African countries are the most vulnerable to climate change. In Asia and the Middle East, despite most countries having green parties, these are minimally represented in national legislatures.

Even within Europe itself, the hotbed of green politics, notable regional divides remain. While green parties thrive in Western Europe, they enjoy nowhere near the same popularity levels in Eastern Europe, where unemployment rates are higher and economic growth is slower. This divergence has been highlighted in surveys of primary concerns in different EU countries. While climate change is a huge issue in western and northern European countries, residents in Eastern Europe and even in a few southern countries are more worried about economic growth, youth unemployment and migration.

Having strong green parties and prioritising green politics may be a privilege only available to advanced democracies with mature economies, mostly in the culturally progressive West. In many Asian, Middle Eastern, African, Latin American and even Eastern European countries, political and economic growth is in a developmental state that may not enable the luxury of green parties. Similarly, political and social culture tends to be more conservative in these regions of the world, making progressive green policies less appealing, especially if they might come at the short-term expense of economic growth.

This might be the biggest blind spot for green parties. Yes, they are generally on the rise, but they are also tailor-made for the West, and in their current form are not a culturally or politically-viable option in most of the world. Global green party alliances do exist, but they need to adapt their messaging and focus on how to sell themselves in countries where priorities may be vastly different.

Of course, where green parties have been successful, trends are positive. Back in Germany, at this stage of the race, it looks unlikely that the Greens will be able to upset the other two establishment parties, with Olaf Scholz’s pragmatic Social Democratic Party seemingly holding all the momentum.

But even if the Greens are unable to catch up, green politics have become a fixture in Germany and Europe. Current polls indicate that no party is poised to win a majority of the vote, so whoever wins the majority of Parliamentary seats will be tasked with forming a coalition government, within which the Greens will in all likelihood feature very heavily. A coalition government with a large Green Party presence can only be a good thing for environmental policy, as Baerbock has pledged that her party will only enter a coalition government that commits to staying within the Paris Agreement target of keeping temperature rise below 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

All of this makes Baerbock, her party and their politics central to the future of Germany. While green parties have a long way to go in making their case in the developing world, the fact that they are gaining traction in wealthy and advanced economies is nonetheless significant. These are the planet’s biggest emitters and their actions will be crucial in drawing down global carbon levels. The Green Party’s rise in Germany is a good sign, and if their policies work well there, its precepts can hopefully be translated to the rest of the world.

Featured image by: Flickr