The Paris Agreement outlines a framework to limit global warming to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and pursue efforts to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C. The 1.5°C goal, among other ambitious targets of the Paris Agreement, were championed by the High Ambition Coalition, an unofficial accord between signatories of the Paris Agreement to pursue more ambitious climate targets and protect the world’s most at-risk nations. Current temperature rise projections indicate a likely temperature rise of 2.7°C by 2100, which would be disastrous for the nations who champion the High Ambition Coalition. But the story of the coalition’s formation may also show us what needs to be done to prepare for climate change-induced migrations, arguably the most severe consequence of the climate crisis.

—

The High Ambition Coalition was critical to developing the Paris Agreement’s more ambitious targets. In addition to its main goal of keeping global temperature rise below 1.5°C, the High Ambition Coalition introduced other significant climate targets to the Paris Agreement, including a pathway to net-zero global emissions by the second half of the century and a five-year cycle for countries to update their commitments to mitigate emission reductions.

The coalition was formed via the unrelenting politicking of Tony de Brum, Foreign Minister of the Marshall Islands, a low-lying island nation in the South Pacific. Mr. de Brum managed to garner the support of developed and developing countries alike in the months leading up to the 2015 climate summit that finalised the Paris Agreement. Over the final few days of negotiations, Mr. de Brum announced the coalition with over 100 unofficial member countries and its targets, creating the necessary momentum to incorporate more ambitious goals into the agreement.

The Marshall Islands is an equatorial low-lying island country in the Pacific. Together with similar countries, such as the Maldives, Tuvalu and Kiribati, the Marshall Islands has a vested interest in establishing a 1.5°C temperature rise target. For these countries, any rise over 1.5°C will leave them vulnerable to devastating impacts from sea level rise. In fact, Kiribati is set to be the first country to be submerged as a result of climate change.

As developed nations struggle to meet the general targets of the Paris Agreement, let alone the more ambitious ones, countries such as the Marshall Islands are poised to be the first to suffer from the most severe effects of climate change in the shape of climate-induced migration. At this stage, the question of whether or not forced migration can be avoided is becoming increasingly irrelevant, as the focus of the world’s most at-risk countries turns to how they can survive and adapt in a warmer world. The nature of the High Ambition Coalition’s formation indicates that such targets may still be achievable through dedicated coordination and leadership.

‘1.5 to Stay Alive’

In the buildup to the Paris negotiations, an unofficial global campaign emerged that called for ambitious temperature rise mitigation targets. The mantra ‘1.5 to Stay Alive’ represents the interests of at-risk island nations from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

The goal of keeping global temperature rise below 1.5°C is one that is shared by low-lying coastal and island countries worldwide. Common concerns over the impacts of climate change on these lands led to the formation of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) in 1990. AOSIS is an intergovernmental organisation that consolidates the voices of small island developing states (SIDS) with regards to climate change and sea level rise. The organisation acts as a coordinated force for SIDS to address the United Nations and other transnational institutions.

While the impacts of climate change may still appear as an abstraction in many parts of the world, the threat of sea level rise for SIDS such as the Marshall Islands is tangible and urgent.

The Marshall Islands are spread over 29 atolls, comprising a total of around 1,225 islands and islets. The highest elevation on the Marshall Islands at high tide is six metres, but most of the land lies between zero and two metres above sea level. The furthest inland point is around 600 metres from the coast, but for the most part, the islands are flanked closely by water on both sides, and most Marshallese residents live only a few minutes walk from the shore.

These factors make the Marshall Islands, and many other SIDS, vulnerable to even small changes in sea level. While narratives of sinking islands being reclaimed by the sea tend to prevail in the public eye, this is misleading, as low-lying landforms become uninhabitable long before they disappear beneath the water. Before land becomes completely submerged, rising sea levels can deprive it of any and all value due to waterlogged soil, erosion and salinisation. Combined with persistent droughts, land where people live and work can become unusable, unprofitable, and increasingly unsafe.

Particularly strong seasonal high tides, known as king tides, naturally occur fewer than five times a year, often damaging buildings and farms and forcing people to evacuate. The inundations caused by king tides provide a glimpse of future damages, as rising sea levels are making king tide-level flooding the norm year-round. The damage caused by king tides is exacerbated by deteriorating natural reef barriers offshore.

You might also like: Climate Deniers Shift Tactics to ‘Inactivism’

Image 1: Difference between regular water levels and king tides off the coast of Majuro, capital of the Marshall Islands; The Guardian; 2015.

A study by the University of Hawaii examined the potential impacts of unmitigated emissions and sea level rise over the course of the century on the Marshall Islands, specifically addressing the issue of salinisation. In addition to flooding, saltwater surges rapidly deteriorate inland freshwater resources, soil quality, agricultural plantations and forests. These impacts deplete ecological services, benefits that humans receive from healthy natural environments and ecosystems.

‘1.5 to Stay Alive’ reflects the urgency of the situation for many SIDS, whose populations are now seeing first-hand what climate change has in store for their future. The statement has been employed by climate activists calling for more ambitious action by leading governments and emitters. Despite being responsible for less than 0.00001% of global emissions, the Marshall Islands will be among the first to suffer from climate change’s most disastrous effects.

The High Ambition Coalition

While the world’s leading carbon emitters and economic powerhouses settled on a 2°C temperature rise target, the Marshall Islands and other at-risk countries internally acknowledged that more ambitious goals were needed.

And so Tony de Brum began his unofficial campaign. The High Ambition Coalition was born through informal discussions during preliminary climate summits in mid-2015. By the time of the Paris negotiations in December, de Brum was in regular meetings with ministers and representatives from across the world, including Miguel Arias Cañete, the EU climate commissioner, and Todd Stern, the US chief negotiator.

At the time of its announcement during the final days of negotiations, the coalition included poor and wealthy nations alike. De Brum emphasised the resilience of the coalition’s goals, and how they addressed the needs of all nations, stating: “This group is not going to allow this thing to be diluted to the point that it’s a watered down agreement with really no teeth. I think that’s important. And also that we will not leave anyone behind.”

Certain high emitter countries opposed some of the coalition’s targets. India, for instance, was opposed to the idea of reviewing emission targets every five years. The US lobbied against making certain goals of the coalition legally binding, such as the requirements for wealthy countries to financially support energy transitions in the developing world.

Ultimately, despite the objections, the goals of the High Ambition Coalition were written into the Paris Agreement. De Brum’s successful efforts to bridge international divides deserve to be acknowledged. The Marshallese representative managed to, at least temporarily, broker a global alliance that transcended political squabbles between nations, and arguably dragged the Paris negotiations across the finish line.

Tony de Brum passed away in Majuro, capital of the Marshall Islands in 2017. Speaking of de Brum’s role in mediating the signing of the Paris Agreement, Todd Stern said: “We all owe a debt to Tony for getting Paris done. When I think of people who were meaningful in getting the Paris deal, he is definitely on the short list.”

Despite de Brum’s passing and the group’s informal structure, the coalition continues to be a vocal actor at the transnational level. The High Ambition Coalition has recently outlined plans to address a green recovery from recessions induced by COVID-19, specifically discussing how up to 60% of global recovery spending could be directed towards developing a green economy and low-carbon jobs.

In view of the UN’s 26th Climate Change Conference (COP26) in November 2021, the High Ambition Coalition released a statement in February 2020, cosigned by various EU member states, SIDS and other countries. The statement reaffirmed the High Ambition Coalition’s targets, specifically to review countries’ NDC plans. Five years on from the original Paris negotiations, countries will have to present updated plans to reduce emissions at COP26. The coalition aims to ensure the delivery of these updated NDCs, as well as long-term greenhouse gas reduction strategies, national adaptation plans and climate finance commitments.

Failures of Jurisdictional Enforcement

The High Ambition Coalition served a pivotal role to affirm the Paris Agreement, and can continue to be a major uniting force in policing and pressuring other Paris signatories. However, despite best intentions, jurisdictional failures to enforce mitigation measures continue to present a significant obstacle.

The main criticism that is justifiably levied against the High Ambition Coalition is that many of its unofficial members are not on track to even meet the 2°C goal. For instance, EU member states have been frequent participants in pledges and statements made by the High Ambition Coalition, however, if all countries emitted at the same rate as the average EU state, global temperature rise by 2100 would be between 2 and 3°C.

Current best-case scenarios place global temperature rise at a median 2.1°C by 2100. In worst-case scenarios, a temperature rise of 1.5°C could occur by the early 2030s, and likely before 2042.

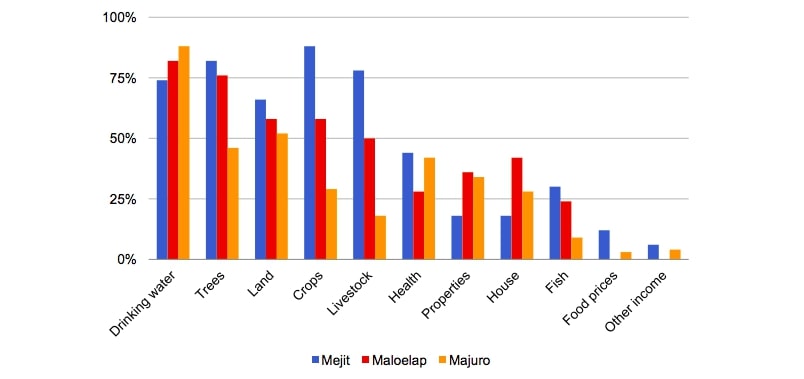

Fig. 1: Impacts of climate-related stressors in the past 5 years (percentage of households affected) on three most populated Marshall Islands atolls; Van der Geest et al; 2020.

Despite presumably being unable to accomplish its primary goal, calling the High Ambition Coalition a failure would be dismissing its accomplishments. The bleak picture painted by current temperature rise projections speaks more to the jurisdictional failure of the transnational system to police and properly enforce emission mitigation pledges, or account for the more tangible impacts of climate change on poorer countries with low emission rates.

Climate change-induced migration is an uncomfortable topic that most policymakers tend to avoid, due to its massive scale and dire implications, as well as its relatively abstract nature for most of the developed world. For the Marshall Islands and other countries in similar circumstances, the often-unarticulated impacts of climate change are rapidly becoming reality.

The Marshall Islands’ Cautionary Tale

While the most severe global impacts of climate change may yet be avoided or at least mitigated, current emissions rates and projections indicate that many developing countries with fewer resources will encounter significant challenges over the coming decades. As one of the first countries to suffer the brunt of climate change and resulting forced migration, the Marshall Islands may provide an early blueprint of the political reality behind climate migration.

Within the context of migration, the Marshall Islands has been a beneficiary of a unique compact of free association with the US since 1986. The compact developed as a means of reparations on behalf of the US. During World War II, the US used the Marshall Islands as a nuclear testing site, specifically the Bikini Atoll, causing large-scale evacuations and relocations. Swathes of ancestral land remain highly radioactive to this day. The compact absolved the US of any legal responsibility related to its nuclear testing program, while granting the Marshall Islands government a reparatory payment of $150 million and certain rights for Marshallese citizens.

Among other things, the compact allows Marshallese citizens freedom to study, work and live in the US without the need for visas or permits. As a result, many Marshallese have moved to the US since the compact was agreed upon. As of 2018, approximately one third of Marshallese citizens live in the US, around 30,000 people.

A 2020 study analysed the links between migration trends, climate change and ecological services. Climate change was not often cited as a direct reason behind the decision to emigrate. Primary motivations were education, healthcare, employment and family visits. However, a more nuanced analysis of respondents’ answers revealed how climate change has indirectly influenced migration.

As ecological services collapse, meaning that the land is increasingly unable to provide for basic needs, residents become open to leaving. For an economy still reliant on agricultural production, deteriorating ecological services has led to a substantial rise in unemployment. More diversified employment opportunities in the US therefore become an appealing option for the Marshallese. The study also found that 62% of Marshallese migrants felt that, due to environmental concerns, a future return to the islands would not be possible.

It should be noted that more research on the motivations behind these migrations is required, as empirical studies of climate change-induced migrations are sparse and the field is in its relative infancy.

Fig.2: How climate change will impact migrations; The Marshall Islands Climate & Migration Project; 2019.

Emigrants’ concerns over worsening healthcare standards are also indirectly tied to climate change. Over the past few years, the Marshall Islands have experienced frequent outbreaks of dengue fever, a disease which had previously only emerged sporadically. Between July 2019 and January 2020, an outbreak of dengue was presumed to have infected up to 8,000 of the Marshall Islands’ resident population of 53,000. As the islands’ climate warms, the country is becoming an increasingly suitable breeding ground for the species of mosquito that carries dengue, among other serious diseases.

The options for Marshallese residents are either to stay and manage dramatic lifestyle changes for as long as they can, or leave. Given current trends, the end outcome will be the same, the only variable being time.

This is what climate change will soon look like on a global scale.

The case of the Marshall Islands demonstrates how future climate change-induced migrations could play out. People tend to migrate not because of climate change itself, but because of how a changing climate can affect employment, livelihoods, health, food security and overall well-being. These impacts will be felt long before land becomes completely uninhabitable, and under current trends will drive mass movements from affected countries over the coming decades.

Developing countries will be the most severely affected. This is partly due to circumstance, as the tropical countries that will be most impacted by climate change tend to be developing states. Reliance on agriculture and lack of capital that can compensate for deteriorating ecological services also plays a role. Policymakers in wealthier countries will need to begin planning for the massive scale of this eventuality, and incorporate institutional structures that can support climate refugees.

Once more, the circumstances of the Marshall Islands present a potential blueprint for countries to follow. The Marshall Islands-US compact permits freedom of movement and work between the two countries. This has allowed communities of Marshallese to grow within the US over the past 30 years. By far the largest expatriated Marshallese community is in Springdale, Arkansas, a city with a population of around 70,000 that is home to 15,000 Marshallese. Springdale is the headquarters of Tyson Foods, the world’s largest poultry producer, and has attracted Marshallese workers since the 1980s. Springdale boasts 35 Marshallese churches, a consulate and a number of nonprofit organisations supporting migrants and promoting Marshallese culture.

Jobs such as those provided by poultry producers in Springdale are widely available and do not require skilled labour, allowing any migrant to start working immediately upon arrival. The value of this freedom of movement should not be underestimated. It is a right that most migrants wait years or decades to obtain.

Similar policies modelled on the Marshall Islands-US compact will need to be implemented on a much larger scale globally to accommodate future climate refugees. Compacts that can waive or expedite work permits and visas can facilitate adjustments, and keeping communities together with robust support systems in environments such as Springdale will be critical.

No model or policy will ever be ideal. In the case of the Marshall Islands, over 3,000 years of history and culture that is inextricably tied to the land is being effaced in the span of less than a century. Relocating entire populations to other countries brings a set of cultural and linguistic difficulties. Children born abroad will encounter challenges reconciling their heritage without a physical attachment to history through land. A nation relies on its land for its perceived permanence and stability, so land is faced with the constant threat of irreversible erasure, a population can lose a critical link to its identity. A person can move easily, a nation cannot.

The plight of the Marshall Islands and its people demonstrates what effects unmitigated climate change will have in the long term, and it highlights who will pay the highest cost. The efforts of the Marshall Islands to establish the High Ambition Coalition are important and prove that coordinated efforts to mitigate climate change impacts are possible when the inefficiencies of political infighting and jurisdictional inaction are pushed aside.

In 2014, Marshallese poet and activist Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner addressed the world at the UN Climate Summit. As part of her remarks, Mrs. Jetnil-Kijiner recited a poem she had dedicated to her newborn daughter, outlining the looming threats for small island nations, how the global community is reacting, what is in danger of being lost and what possible futures her daughter and the younger generation of Marshallese children could experience. “We deserve to do more than just survive, we deserve to thrive” Mrs. Jetnil-Kijiner said in her remarks.

Standing ovations at the UN General Assembly are generally rare. Mrs. Jetnil-Kijiner’s lasted a full minute.

Featured image by: Flickr