Louisiana’s air quality, particularly in Cancer Alley, is deteriorating, putting black residents at a higher risk of developing cancer. The Biden administration’s decision to halt an investigation, despite clear evidence of discrimination, raises concerns about environmental injustice. While the EPA’s lawsuit targets emission reductions from Denka Performance Elastomer LLC, detractors worry that the administration’s withdrawal establishes a concerning pattern, leaving the fight against toxic pollution and racial injustice in limbo and affecting the well-being of impacted communities.

—

Across the United States, there has been a consistent and laudable trajectory of improving air quality over the recent decades, leading to improved well-being and a more favorable environment for all. However, the same cannot be said for Louisiana, a state that is experiencing a concerning reversal in the quality of its air. But there is a depth beyond initial impressions. This is not just about industrial pollution and environmental degradation; it is an exposition of racial disparity and a blatant demonstration of how marginalized black residents are disproportionately exposed to danger.

Earlier this year, the Biden administration decided to end the investigation into allegations of racial discrimination against Louisiana officials, albeit with initial evidence of discrimination. This was regarding the increased cancer risk faced by Black residents in an industrial area. The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) assertion that a resolution is unattainable by a July deadline effectively closes a door that many activists in predominantly Black communities hoped would lead to better health outcomes. This just adds to how the gears of bureaucracy often turn slowly, leaving those most vulnerable to environmental hazards in a perpetual state of trepidation.

You might also like: Top 6 Environmental Issues the US Is Facing in 2023

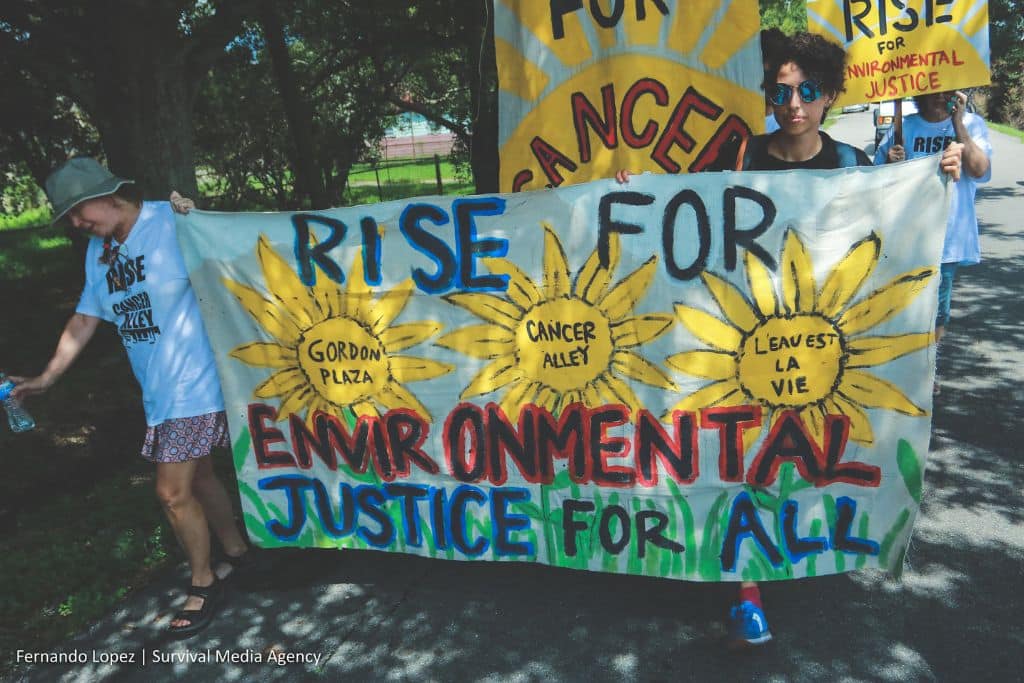

Louisiana’s Cancer Alley

In 1987, when Jacobs Drive residents in St. Gabriel, a low-income community with about 50% of its population from correctional facilities, noticed a surge in cancer cases, they termed it “Cancer Alley.” The term expanded to cover an 85-mile stretch along the Mississippi River, from New Orleans to Baton Rouge, including several parishes. The term Cancer Alley is not only jarring in its sound, but it also detrimentally changed the way residents live their lives. Many ominously called it “Death Alley,” with the Port of South Louisiana leading as the largest port by tonnage in the Western Hemisphere (and the second busiest trade zone for energy and grain in the US).

Despite claims that industrial plants “benefit” minorities through employment, a 2003 study revealed low African American employment (4.9%-19.4%) compared to the county’s overall population (49.2% in 2000). This industrial dominance is not without its discernible downsides. Refineries, waste pits, and the hazardous consequences of industrial processes mar the landscape. The Denka/DuPont neoprene plant in St. John the Baptist Parish, now owned by Denka, flagged concerns with the EPA due to a cancer risk from air pollution over 700 times the national average.

Environmental Racism

Witnessing the unfair allocation of environmental impacts based on race from the same people who also hope to prevent our planet’s downfall, we must acknowledge that, in reality, inequality not only weakens the core of environmental initiatives but also drives wedges among diverse communities committed to a shared goal.

Environmental racism is a deeply rooted issue that manifests in the disproportionate exposure of minority communities, particularly those inhabited by people of color and low income, to environmental hazards and pollutants. These communities often find themselves situated near industrial facilities, waste disposal sites, and other sources of pollution, arising to adverse health outcomes.

The historical context of discriminatory land-use policies and zoning decisions has perpetuated this injustice, concentrating environmental burdens in areas with vulnerable populations. The relentless destruction and exploitation of lands and communities endured by people of color prompted them to gather at the National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991 to take a stand against the harm inflicted on their lands and communities. Out of this came the Principles of Environmental Justice, outlining 17 core beliefs.

This environmental injustice, deeply rooted in over 500 years of colonization and oppression, has led to the poisoning of their surroundings and the genocide of their people. The principles address the systemic issues perpetuating this harm, from toxic production and hazardous waste disposal to discriminatory public policies. The document calls for an end to these destructive practices and advocates for the right of communities to be equal partners in decision-making processes.

You might also like: How Marginalised Groups Are Disproportionately Affected by Climate Change

The End of Cancer Alley Investigation

In April 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) investigated complaints about whether Louisiana officials had unfairly exposed Black residents to a higher cancer risk and had breached the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Federal authorities found proof of discrimination and pressured the state to improve its supervision of industrial plant emissions. According to the EPA, evidence showed increased cancer risks for Black residents near a chemical plant in Louisiana, prompting the Agency to criticize state officials for allowing high air pollution levels while downplaying the danger.

In October 2022, the EPA posted a letter on its website. The communication to Louisiana authorities discusses initial findings of racial disparity involving two state departments within the entire corridor stretching from New Orleans to Baton Rouge. This includes a facility identified by the EPA as a significant emitter of a cancer-causing substance, as well as a proposed plastics complex.

The letter asserts that there is cogent evidence to suggest that the actions or inactions of these departments have negatively affected and continue to harm Black residents in St. John the Baptist Parish, St. James Parish, and the officially named Mississippi River Chemical Corridor, which spans 85 miles. The letter also indicates that the state Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has allowed the Denka polymer plant to subject nearby residents and elementary school children to elevated chloroprene levels for many years, thereby increasing their cancer risk.

In March 2023, Federal officials filed a lawsuit against Denka Performance Elastomer LLC. The complaint demands reductions in toxic emissions. Despite emission reduction efforts over time, on behalf of EPA, the Justice Department contends that the plant remains a prominent threat to public health. Michael Regan, the EPA Administrator, has asserted that Denka’s efforts to reduce emissions and ensure the safety of the nearby community have not “moved far enough or fast enough.”

However, despite initial promises of accountability, the Biden administration’s abrupt discontinuation of the investigation in June 2023 has left the battle against environmental injustice unfinished. Despite initial evidence of racial discrimination, the EPA took action against Denka, a polymer plant, but Louisiana made no commitments. Activists criticize the retreat, fearing it sets a dangerous precedent and expressing dismay over the potential curtailment of civil rights investigations. The EPA aims to analyze health risks in the community near the Denka plant but won’t force state participation. Another complaint over emissions from a proposed chemical plant was disposed of due to permits in litigation.

To date, the lingering issue remains an oppressive burden for residents in a state grappling with toxic pollution that adversely affects their physical health, coupled with the mental toll of racial injustice. Sharon Lavigne, President and Founder of Rise St. James vividly describes the situation, likening it to a death sentence, as if they are “getting cremated, but not getting burnt.” Only through sustained efforts can we hope to dismantle the oppressive barriers that threaten the well-being and future of affected communities—an initiative that the government should be leading. This fight is far from over, and while investigations may be closed, the conversation on environmental injustices must not be silenced.

Featured image: Flickr/350. org

You might also like: Air Pollution: Have We Reached the Point of No Return?