Are we running out of water? Only 3% of the water on the Earth’s surface is freshwater. Less than 0.5% of that is accessible for consumption as drinking water. If no urgent action is taken, an increasing number of cities worldwide are expected to experience severe water shortages. Recent analyses by the BBC ranked cities such as Beijing, Tokyo and London among those most likely to run out of drinking water in the near future.

—

Is the World Running Out of Water Because Climate Change?

The short answer: yes. Climate change is expected to severely alter the quantity, quality and spatial distribution of global water resources. Warmer temperatures increase evaporation, change the holding capacity of moisture in the air and alter rainfall patterns. The most recent IPCC report concluded that, in general, wet regions will get wetter and dry regions will get drier. Increases in the frequency and intensity of extreme events like droughts and heatwaves will also contribute to water stress and water shortages.

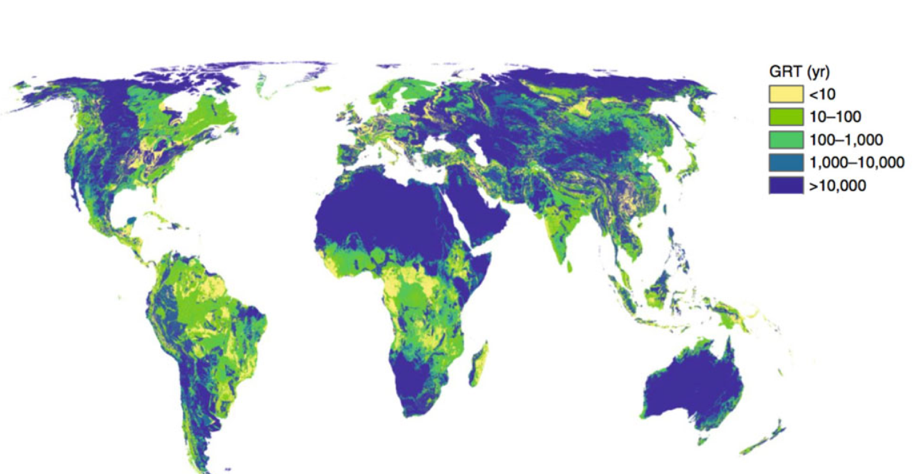

A ground-breaking study on the impacts of climate change to groundwater resources was recently published in Nature Climate Change. The study showed that groundwater stored in aquifers, which provides 36% of the world’s domestic water supply for over 2 billion people, is highly sensitive to future climate change.

Groundwater is stored in underground aquifers that are replenished by rainfall and soil moisture. Could this groundwater be depleted, and if so, when will the world run out of water? Researchers found that 44% of all aquifers globally will be fully impacted and depleted as a result of climate change in the next 100 years due to changes in the intensity and pattern of rainfalls. Underground water reserves in drier regions are naturally slow at adjusting to above-ground atmospheric and climactic changes, but over-abstraction and other impacts of extreme drought may still exacerbate regional water shortages.

You might also like: Water Scarcity: How Climate Crisis is Unfolding in India

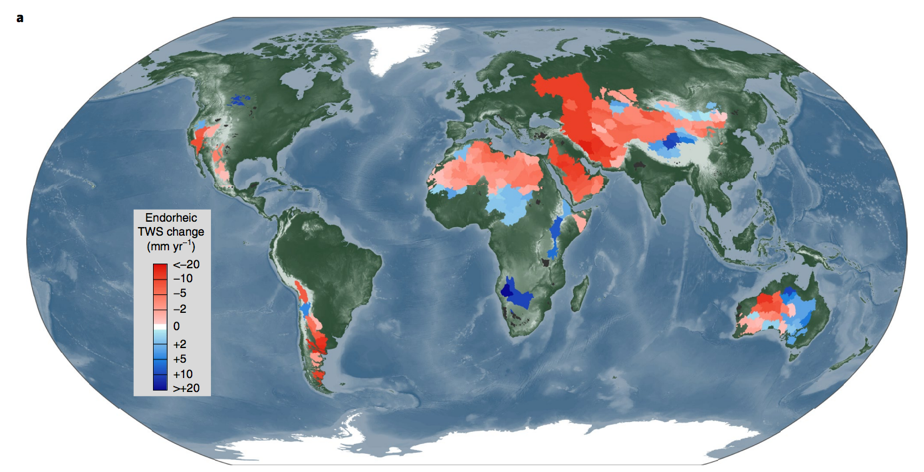

Another recent study concluded that total water storage in landlocked river basins has declined significantly over the past few decades. Using gravity satellite observations from the NASA GRACE satellite, researchers calculated that water storage is declining by 100 billion tonnes per year, which is attributable to climate change and unsustainable water management. Given that most of the landlocked basins are in arid regions, there are significant implications to regional water stress.

A consequent impact of water storage decline is its contribution to sea level rise. Because of conservation of mass in the earth system, water lost in landlocked basins impacts global sea level through changes to the water vapour flux. Water loss in landlocked river basins accounted for about 10% of global sea level rise observed in the past 10 years.

Why is the Water Cycle Important in Preventing the World Running Out of Water?

There is a growing consensus around the idea that anthropogenic climate change is already significantly changing the global water cycle and that the sustainability of freshwater sources is being compromised.

Urbanisation and an exponential increase in freshwater demand for households are driving factors behind water shortages, especially in regions with a precarious water supply. Cape Town, the first modern city to effectively run out of drinking water in 2018, has suffered because of the confluence of extreme drought, poor water resource management and over-consumption. Pipes were dry and thousands were left queuing for drinking water. Similarly, China is also at risk of running out of water; the total renewable water resources per inhabitant is 2 018 cubic meters each year- 75% less than the global average, according to the World Bank.

Disruptive technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning may hold the key for new and bold solutions. Smart hand-pumps that leverage AI to analyse groundwater use and predict pump failures has been experimented in rural Kenya resulting in water use optimisation and thus reducing wasteful dispersion of this increasingly precious, liquid gold.

A smart grid water management approach with an Internet of Things (IoT) system could be the answer. An IoT system refers to a network of physical objects that have been embedded with communications software, wireless environmental sensors, and automated control systems. An IoT system can monitor structural integrity and environmental factors, and can communicate with the rest of the system to perform real time risk analysis. IoT infrastructures have been highly successful in optimising the efficiency of wind and solar power farms by minimising risk and redundancy and maximising output. A water management IoT system can monitor air, water, and soil conditions autonomously and waste can be reduced via timely responses to weather events and water demand. Governments should invest in IoT research with a view towards significant long-term savings and increased efficiency in water management.